Paul Robeson, the Scholar

Paul Robeson, the Orator

Paul Robeson, the Traveler

Paul Robeson, the Entertainer

*** LEGENDS ***

‘A scholar, athlete, lawyer, singer, actor, activist and freedom fighter’

By Yussuf J. Simmonds

Managing Editor

A MAN AMONG MEN

As a singer and a major concert star, Paul Robeson was the first to popularize Negro spirituals and the first Black actor to portray “Othello” on Broadway in the 20th century, and still holds the record for the longest run on Broadway for that portrayal. An all-American professional athlete, writer, orator, scholar, lawyer and freedom fighter, he was well known for his international activism for social justice. Despite his impressive resume, he was hounded and persecuted by the U.S. government in collaboration with the media, so much so, that his presence and accomplishments have only recently begun to be listed in few “mainstream” books and literature.

Many Black advocates and historians continue working to have Robeson’s legacy placed among the giants of human history and to restore his name correctly to history books and sports records. Robeson’s memory continues to be honored globally with posthumous awards and recognition. In addition, he plays a prominent role in the history written by Blacks and his pioneering role as a fighter for human rights has become legendary. Robeson was fighting for civil rights before it was fashionable and most times, all by himself.

Born in April 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, Robeson’s father was an escaped slave, who became a pastor, and his mother came from a Quaker family; she was almost blind and died when Robeson was 6 years old. He had three brothers and one sister. The family relocated to Somerville, New Jersey, when Robeson was 12 years old. There he went to school and eventually graduated with honors from Somerville High School, where he had excelled in academics, acting, singing and athletics, and which resulted with a full academic scholarship to Rutgers University.

As in high school, Robeson excelled at Rutgers; he was the third Black student accepted at the university and the only Black student during his time on campus. He was the class valedictorian, and his classmates envisioned that he would become the first Black governor of New Jersey by 1940 and leader of the “colored” race in America. His academic accomplishments were expected since he had come to Rutgers on academic scholarship, but Robeson achieved varsity letters of excellence in football, baseball, basketball, and track and field. He was a one-man team juggernaut; the football coach described him as “the greatest to ever trot the gridiron.”

From Rutgers, Robeson entered Columbia Law School. He worked as an athlete and a performer to help pay his way through law school. In addition, he played professional football in the American Professional Football Association (the forerunner of the National Football League) with the Akron Pros and Milwaukee Badgers; and served as assistant football coach at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. Robeson used all his athletic skills and talents to survive during a time when being Black–and in many instances, the only Black–was not popular or employable. That meant using his talents as an athlete and actor wherever and whenever possible. Robeson hooked up with a traveling basketball team during the 1918-1919 period and three years later, he starred in a play, “Taboo” in New York; it was later renamed “Voodoo.”

THE TURNING POINT

Two years before graduating, Robeson married Eslanda Cardozo Goode, the head of the pathology laboratory at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City who came from a well known family in New York’s social circles. Essie (as she was affectionately called) supported him in his career and even became his business manager. Their marriage was rocky; Robeson was reported to have had extramarital affairs. After he graduated from Columbia Law School, he was hired at a prestigious law firm in New York City. Because of racial norms of the day, though Robeson was a qualified attorney-at-law, racism reared its ugly head at the law firm and he quit after a white secretary refused to take dictation from him because of his race.

Because he was multi-talented, Robeson was able to cross over to acting and singing in the 1920s and beyond when his career as a practicing attorney fizzled due to overt racism. With the voice of a renowned, bass-baritone concert singer and a commanding presence, he found fame as an actor and singing star of both stage and radio. Robeson’s renditions of old spirituals were acclaimed as he brought them to the concert stage. He went on to act in and narrate over a dozen films in the United States and abroad. During the same period, his political and racial consciousness began to develop and he was becoming one of the first actors to demand (and receive) final cut approval on a film. It was more profound since being a Black actor, Robeson was pioneering the way for generations of future actors to acquire roles that had dignity and emphasized pride in their African heritage.

Prior to his role in “Taboo,” Robeson had played Simon in Simon the Cyrenian at the Harlem YMCA and at the Sam Harris Theater in Harlem. In 1924, he did the title role in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Emperor Jones” and then “All God’s Chillun Got Wings,” in which he portrayed the Black husband of an abusive White woman who, resenting her husband’s skin color, destroys his promising career as a lawyer–a radical and revolutionary performance for a Black man judging by the standards of the day. That was followed by his role as Crown, in the stage version of DuBose Heyward’s novel “Porgy,” that laid the foundation for the opera, “Porgy and Bess,” which later on became a movie.

Robeson went to England where he studied phonetics, Mandarin, Swahili and African dialects at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London in 1934. There he formed a strong relationship with Yolanda Jackson; during that time, his wife seriously considered divorcing him, but the relationship with Jackson ended abruptly. (Essie and Robeson stayed together until her death in December, 1965. They had one child, Paul Robeson, Jr., born November 2, 1927 and like his father, he became multi-lingual). Robeson was masterful as a linguist; he was able to converse in 20 languages and was fluent or near fluent in 12. His standard repertoire included songs in many languages as diverse as Chinese, Russian, Yiddish and German.

BECOMING INTERNATIONAL

While in London, Robeson met with African students, who named him and Essie honorary members of their Students’ Union. They became acquainted with Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, future presidents of Ghana and Kenya, respectively. Robeson drew parallels between oppressed peoples exploited in the colonial possessions of Western Europe, and Blacks in the United States, abused by segregation and lynching. (He was a writer for periodicals such as Freedomways Quarterly for whom Nkrumah, Kenyatta, Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. also contributed).

By making movies on both sides of the Atlantic, Robeson was gradually becoming an international figure and his career, increasingly political. Wherever he went, Robeson voiced dissatisfaction, first with movie stereotypes and then in matters of race. Some of his roles in both the US and British films were the first parts ever created displaying dignity and respect for Black film actors–as he had done on the N.Y. stage–thereby paving the way for future Black actors. Throughout his career Robeson made about 11 films–seven were British–including “Body and Soul,” “Proud Valley,” “Song of Freedom,” “King Solomon’s Mines,” “Borderline” and “Showboat.” His rendition of “Ol’ Man River” accompanied the film “Show- Boat” and was a box office hit in 1936 and the most frequently shown and highly acclaimed of all his films.

Along with his international stature as a spokesman against racism in the U.S. and abroad came governmental scrutiny. Robeson was unwavering in his stand against all racial oppression worldwide and he had an ideal platform to voice his concerns. The U.S. was a hotbed of racial segregation and the civil rights movement was beginning to bubble; and many Western European powers had their “colonial foot” on Africa’s neck. Beginning in the late 1940s, Robeson became a prime, surveillance target of several governmental agencies–of the U.S. and its allies -including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), MI5 (British Military Intelligence) and some sources also include Mossad (Israeli Intelligence Agency, after 1949).

His ability as an artist was severely curtailed, Robeson’s passport was revoked. Federal laws and the mood of many in the nation–the McCarran Act, the second Red Scare and McCarthyism–in addition to being Black made it easy to strip Robeson of his fame fortune and good name. Even though President Truman wrote, “In a free country, we punish men for the crimes they commit, but never for the opinions they have;” that obviously did not refer to Robeson. (Also blacklisted with him during the McCarthy Era were Harvard scholar, author and activist, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois; and poet and writer, Langston Hughes).

The only sin that triggered Robeson’s persecution was his speaking out on his beliefs in socialism and friendship with the Soviet peoples; his tireless work towards the liberation of the colonized peoples of Africa, the Caribbean, Asia and the Australian aborigines; his support of the International Brigades; his passion to promote anti-lynching legislation and end racial segregation in the U.S. and apartheid in South Africa; and many other causes that challenged white supremacism worldwide.

A concert of condemnation fell on Robeson from all quarters including those for whom he was speaking. It was expected that the U.S. Congress would attack his beliefs since they were the ones who were heading his persecution, but many in the Black community marched right along with the White power structure. First in line was the NAACP via the editor, Roy Wilkins, of its official magazine’s “The Crisis,” Robeson was villified for his work on behalf of the liberation of Africa. (Ironically, Robeson received the Spingarn Medal, NAACP’s highest honor later in his career).

Also, Jackie Robinson was ordered to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in Congress where he condemned Robeson for his alleged communist sympathies. He was reluctant to testify, in part because of Robeson had addressed baseball owners on behalf of integration in professional baseball in December 1943, which had paved the way for Robinson’s entry into major league baseball four years later. Though he was never arrested or charged with a crime, Robeson’s FBI file is reportedly one of the largest of any entertainer investigated by the U.S. governmental agencies.

Robeson remained committed to his ideal of socialism for oppressed people, anti-colonialism for Africa and to the end was unapologetic for his political views. His movements restricted to the continental U.S. and stripped of his livelihood in addition to being persecuted, Robeson’s health began fading in his later years. However, as movements of international freedom fighters, and civil and human rights group began to shake off the yolks of colonizers, imperialists and oppressors, Robeson’s words and his works became evident and apparent.

HIS DEATH AND LEGACY

In 1968 for Robeson’s 70th birthday, there were elaborate celebrations all over the world including a three-day celebration in East Germany, and an evening of music and poetry in London at the Royal Festival Hall. (Twenty years later, in 1988, there were similar worldwide celebrations for an imprisoned Nelson Mandela, a man like Robeson for his 70th birthday, including a popular-music concert at Wembley Stadium, London that was broadcast to 67 countries and a viewing audience of 600 million). The Black Commission of the Communist Party USA remarked that the White power structure had generated a conspiracy of silence around Paul Robeson in an attempt to blot out all knowledge of his exploits as a pioneering Black American freedom fighter.

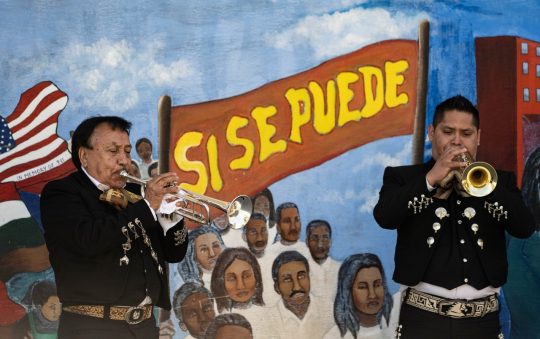

Five years later, more than 3,000 people gathered in Carnegie Hall to salute Robeson’s 75th birthday, though he was unable to attend because of illness, but he sent a taped message that said in part, “Though I have not been able to be active for several years, I want you to know that I am the same Paul, dedicated as ever to the worldwide cause of humanity for freedom, peace and brotherhood.” The guests consisted of a prominent list of who’s who in America including Attorney General Ramsey Clark, Angela Davis, Dolores Huerta, Dizzy Gillespie, Odetta, Leon Bibb, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte (who also produced the show), James Earl Jones, Roscoe Lee Browne, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee and Coretta Scott King. And from around the world, some of the other birthday greetings came from President Julius K. Nyerere of Tanzania; Prime Minister Michael Manley of Jamaica; President Cheddi Jagan of Guyana; President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia; Indira Gandhi of India; Arthur Ashe; Judge George W. Crockett, and the African National Congress.

On January 23, 1976, at age 77, Robeson died of a stroke following complications from a severe cerebral vascular disorder; that was the official version but in fact, years of persecution and torment inflicted by his government greatly contributed his untimely end. His body lay in state for a viewing at Benta’s Funeral Home in Harlem for two days. His granddaughter, Susan Robeson, recalled “…watching this parade of humanity who came to pay their respects…from the numbers runner on the corner to Gustaf VI Adolf King of Sweden.” About 2,500 people attended Robeson’s funeral at Mother AME Zion Church in Harlem where his brother, Ben, had been pastor for 27 years. Thousands more, mostly African Americans, stood outside listening on the public address system, as speaker after speaker, including Belafonte paid tribute to Robeson for his integrity and tremendous courage in the face of extreme adversity. Also in attendance were Poitier, Uta Hagen, Betty Shabazz, Eubie Blake and Paul Robeson Jr., who described his father as “a great and gentle warrior.” He was cremated.

In addition, many in the mainstream media that had demonized Robeson in life celebrated him in death. However, “The Amsterdam News”–like much of the Black press–eulogized him as “Gulliver among the Lilliputians,” and his life would “always be a challenge and a reproach to White and Black America” alike.

Some of the indignities that befell Robeson, his name and his reputation, began to be restored posthumously. His name, which had been retroactively removed from the roster of the 1918 college All-America football team, was fully restored to the Rutgers University sports records, and in 1995, Robeson was officially inducted into The College Football Hall of Fame. Rutgers University Newark also named its student-life campus center and art gallery in his honor; its New Brunswick Campus named one of the cultural centers, The Paul Robeson Cultural Center; and its Camden campus named the library, the Paul Robeson Library.

Paul Robeson Jr. founded the Robeson Family Archives and the Paul Robeson Foundation to safeguard his father’s memory and protect his legacy. During Robeson’s career, he published one book, “Here I Stand,” in 1958, and in 1980, his granddaughter, Susan, published a pictorial biography of her grandfather titled “The Whole World in His Hands.”