Is there space for someone like me in the Black Church?

Like most other people, I was feeling the weight and anxiety of being in isolation during lockdown. I had just changed career paths towards working on my dream as a filmmaker when the whole world just stopped.

As I watched COVID spread across the entire globe, I got a text from my cousin back in New York City, and she let me know that my grandmother had died. I didn’t have the best relationship with my grandmother, but I felt an enormous sense of guilt and loss.

What’s worse is my family couldn’t schedule a timely funeral or burial because the funeral homes were all backed up from COVID. So, I found myself doing something that I hadn’t really done since I was a kid.

I got down on my knees and I started praying. And I felt like a complete hypocrite.

With the most amazing timing in the world, I was approached by PFLAG National about directing a documentary, and I decided to use this opportunity to start exploring my feelings about religion and the Black church. I wanted to see if there was any change; if there was any room for a queer Afro-Latino man to come back to the church, and to have some fellowship.

I grew up in Jamaica, Queens. My single mom had a lot of drug and alcohol problems, and eventually my aunt became my guardian and took me in. My godfather lived in the same building as we did, and he was a preacher, which meant I was always in church. There was no hiding. And when your godfather is on the pulpit, everything feels more personal.

It was around this time when I started having romantic and sexual feelings. I honestly thought I was going to hell. My godfather used to say, “Jesus will love you forever and He’ll love you right on into hell.”

So I had that image in my head. It was an image that God loved me, but He’s going to love me right into the lake of fire to burn forever. And so for my own sanity, my own well-being and mental health, I left the church when I was around 16, which was also the year my mother died.

The church of my youth had an element of slavery survival, an element of homophobia, an element of patriarchy, an element of toxic masculinity, and the long shadow of White supremacy.

The main question that I had as I approached the interviews with the pastors for this film was: “Has the church evolved or changed since I was a kid?” That was really the big driving factor. If I chose to go back to a church now, would it have space for me?

And through those interviews, my impression of the church and of fellowship began to change. Speaking with the Reverends gave me more of an expansive view of religion and spirituality. Rev. Mykal Shannon told me that wherever I go, I’m the living church.

There is power in that kind of faith. There is love. You can be religious, you can be spiritual, you can be queer, you can be Black, you can be gay, you can be trans, and carve out a space for yourself.

The journey of “Taking the Long Road Home” brought me fellowship that I hadn’t had since I was a kid. And I was really missing that. I think it’s beautiful.

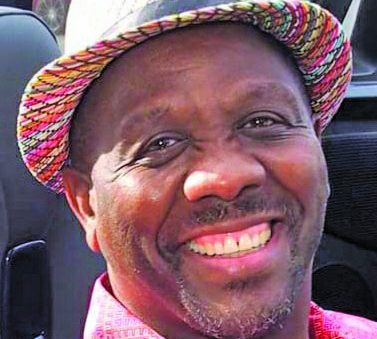

Qiydaar Foster (he/him/his) is a Black Panamanian-American filmmaker based in Los Angeles. A cinephile since childhood, he eventually found his way to his true calling in feature and documentary filmmaking. He is particularly excited to partner with PFLAG National, the nation’s largest and oldest organization serving LGBTQ+ people, their families and allies, to bring the message of “Taking The Long Road Home” to Black families who are on a similar faith journey.

* I derived the content of this op-ed from transcripts of my first-person accounts in the film “Taking The Long Road Home” which premieres online on Wednesday, March 16 at 3:30 p.m. ET.