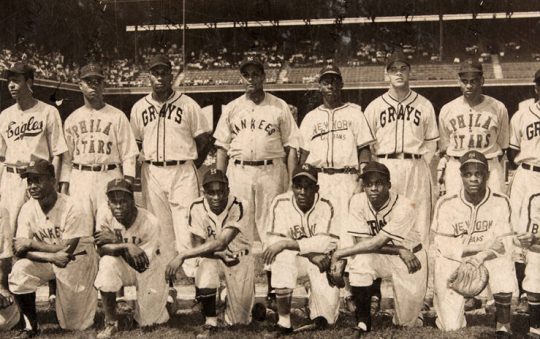

“Satchmo” in action

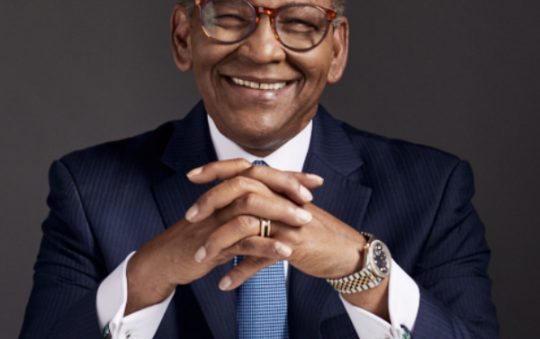

“Satchmo” The Man

Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong

A Jazz Trumpeter who put the ‘J’ in Jazz and the ‘T’ in Trumpet

by Yussuf J. Simmonds

Coming of age in the jazz capital of the world (New Orleans) and nicknamed “Satchmo,” Louis Daniel Armstrong was a world-renowned trumpet player who fascinated audiences with a combination of trumpet-playing and a distinctive, gravelly, musical voice. He was the standard of the American jazz trumpeter and singer.

The grandson of slaves, Armstrong was born in a poor family in New Orleans around the turn of the 20th century when Black and poor were synonymous, and opportunities to rise out of the depths of poverty were scarce to none. (In later years when he attained celebrity status, there always seemed to be a conflict when the year of his birth was discussed; Armstrong stated one date (1901), but never seemed quite certain. It was not until after his death in 1971 that baptismal documentation was uncovered that certified the 1901 date). Early in his life, his father left the family and he spent the rest of his childhood being shuttled between his grandmother, his uncle and his mother.

After attending Fisk School for Boys, Armstrong dropped out at 11 to join a quartet; they sang for money on the city sidewalks to survive. He had an overwhelming survival instinct which led him to do an array of odd jobs to earn money including delivering newspapers, finding and selling discard food to restaurants, and hauling coal in the famed red-light district. These extra curricula activities exposed a young Armstrong to Creole music and allowed him to listen to the bands in the brothels and the dance halls in the Big Easy.

Then he got a job working for a Lithuanian-Jewish family – named Karnofsky – who had a junk hauling business and gave him odd jobs. According to Armstrong in his memoirs, he wrote how they took him in and treated him almost as a family member, knowing he lived without a father; they fed and nurtured him. He also described how the Jewish family was subjected to discrimination by “other White folks” who felt that they were better than the Jewish race. “I was only seven years old but I could easily see the ungodly treatment that the White folks were handing the poor Jewish family whom I worked for.” Armstrong wore a Star of David pendant for the rest of his life and wrote about what he learned from them: ‘how to live-real life and determination.’

(The Karnofsky Project in New Orleans was named in remembrance of the family’s charitable deeds and it was dedicated as a non-profit organization to provide guidance and direction to children who were musically inclined but was financially unable to follow their dreams. The project accepted donated musical instruments with a mission to ‘put them into the hands of an eager child who could not otherwise take part in a wonderful learning experience’ of the world of music).

Periodically, he got into juvenile delinquency trouble and eventually ended up at the Home for Colored Waifs (a place primarily for homeless children) where he learned to play the cornet. As part of its disciplinary program, the Home provided musical training for Armstrong thereby refining his natural musical abilities. At thirteen, he became the leader of the school’s band; a year later he was released and ended back on the streets for a short time until he got his first job at a local dance hall. There he worked hauling coal during the day and playing his cornet at night.

Armstrong also played in several of the city’s brass band parades and developed a taste for listening to older musicians every chance he got. In addition to his passion and dedication, he learned from the regular ‘musicians of the day’ including Bunk Johnson, Buddy Petit, and especially from Joe “King” Oliver, who acted as a mentor and father figure to the budding musician. Armstrong began playing in the brass bands and riverboats of New Orleans, and began traveling with the well-regarded band of Fate Marable, which toured on a steamboat up and down the Mississippi River. During his time with Marable, Armstrong learned to read and write musical arrangements; according to him, it was like going to the University.

In March 1918, Armstrong married Daisy Parker and they adopted his cousin’s 3-year-old son, Clarence. His mother had died soon after his birth and he was born mentally disabled. The marriage did not endure and they separated, and then divorced. The next year, his mentor, Oliver, left New Orleans and Armstrong replaced him, becoming second trumpet in the New Orleans Tuxedo Brass Band. That brought him prominence as a skilled cornet and trumpet player in the 1920s era.

With his brass band and his riverboat experience, Armstrong’s musical star began to shine; he was becoming mature and needed to expand his musical horizon. At 20, he could now read music and he started to be featured in extended trumpet solos as one of the first jazzmen to do this; he injected his own personality and style into his solos and with his distinctive gravelly voice, Armstrong was also becoming an influential singer. His skills included dexterity as an improviser, bending the lyrics and melody of a song for expressive purposes. He also demonstrated vocalizing his music using syllables instead of actual lyrics, a form known as scat singing.

Then he mastered how to create unique sounds using singing and patter in his performances, and he was ready for the ‘big time.’ In 1922, Armstrong decided to join Joe “King” Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band in Chicago where he believed that he would earn enough income so that he could devote his full time to being a professional musician – no more day labor jobs. Chicago was considered a boom town at that time and though race relations were poor – as they were everywhere else in America – the city was bustling with factory and manufacturing jobs for Blacks which translated to plenty to spend on entertainment. And Black folks had ‘cornered’ the entertainment market in many inner cities.

His time with Oliver’s band was financially rewarding and an upliftment to his career. Armstrong’s influence and impact on jazz were growing; he was becoming a trend-setter for the jazz scene and was laying the foundation for future jazz artists. He also shifted from his collective association as a band member to solo performances. His voice became as much his trademark as did his trumpet playing; his stage presence, phenomenal and his influence on music in general and jazz in particular, profound throughout the decades up to and including the 1960s.

His first recordings were on the Gennett and Okeh label, introducing new jazz records across the country as a solo artist while still playing second cornet in Oliver’s band in 1923. About the same time, Armstrong met Hoagy Carmichael with whom he would collaborate later in music and on records. He married Lil Hardin who had a great influence on his career, as his wife and as his manager. At her prodding, Armstrong eventually left Oliver’s band and went to New York where he collaborated and made recordings with Fletcher Henderson’s band for a year before returning to Chicago – in style playing in large orchestras. There he created his most important early recordings and switched to playing classical music in church concerts to broaden his skill and improve his solo play.

As a part of his wife’s management, she urged him into more stylish outfits to complement his performance and to better offset his growing girth. Mrs. Armstrong’s influence eventually precipitated the end of Armstrong’s relationship with Oliver. Their concern about his salary and additional moneys were the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back. In 1924, they parted amicably and shortly afterward, Armstrong relocated to New York City to play with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, the leading African-American band of the day. On his return to the Henderson Orchestra, Armstrong started playing the trumpet as a way to blend in better with the other musicians. This move created a musical combination with Henderson’s tenor sax soloist, Coleman Hawkins, and they made some of the most memorable records for the band during that period.

Adapting quickly to the style of Henderson’s band, Armstrong improved his own trumpet style and experimented with the trombone – his enthusiasm and creativity affected the other members of the band who also took up trying other instruments. His act began attracting other musicians including the Duke Ellington orchestra that would go en masse to catch Armstrong’s performances and to learn from his unique style. However, because of the racial climate of the day, the Henderson Orchestra was playing in the best venues for white-only patrons, including the famed Roseland Ballroom where Black folks were not allowed and most could not afford.

Back in Chicago, Armstrong began recording under his own name and producing hits for the Okeh label including “Potato Head Blues,” “Muggles” and “West End Blues,” which set the music the standard and the agenda for jazz for many years. He worked well to showcase each individual in his bank and developed a reputation as easy going. He teamed up with Earl “Fatha” Hines, Erskine Tate and many of the great musicians of the day, furnishing music for silent movies and live shows, including jazz versions of classical music, such as “Madame Butterfly.” Armstrong re-introduced his version of scat singing and was among the first to record it, on “Heebie Jeebies.” His band became the most famous jazz band in USA and young musicians across the country, Black and White, ‘went crazy’ by Armstrong’s new type of jazz.

After separating from his wife, Armstrong renamed Louis Armstrong and his Stompers, with Hines as the music director. They became fast friends as well as successful collaborators.

Back in New York in 1929, Armstrong played in the pit orchestra of the successful musical Hot Chocolate, an all-black revue co-written by pianist/composer Fats Waller. He also made a cameo appearance as a vocalist, in an early version of “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” that became his biggest selling record to date. He played at Connie’s Inn in Harlem where he staged elaborate floor shows while building considerable success with vocal recordings. His 1930s recordings were highlighted on the new RCA microphone and became an integral part of the ‘crooning.’ Armstrong’s rendition of “Stardust” became one of the most successful versions ever recorded, showcasing his unique sound and style that had already become standards.

With his bubbly cadences and gravelly tone, he re-worked “Lazy River” and it had an enormous effect of younger White singers such as Bing Crosby. After the fallout of the Great Depression, the world of many musicians and their band evaporated, and Armstrong moved to Los Angeles to seek new opportunities. There he played with Lionel Hampton and began to woo the Hollywood crowd, which could still afford a lavish night life. Armstrong appeared in his first movie, “Ex-Flame.”

In L.A., Armstrong was convicted of marijuana possession but received a suspended sentence and he returned to Chicago, and continued playing in bands. Then he visited New Orleans, got a hero’s welcome and saw old friends. After sponsoring a local baseball team, the “Armstrong’s Secret Nine” and got a cigar named after himself, he was on the road again on a cross-country tour. Then off to Europe he went. According to historical records, he earned the nickname Satchmo or Satch, short for Satchelmouth, in 1932, while in London from then Melody Maker magazine editor Percy Brooks who greeted him with, “Hello, Satchmo!” and it stuck.

When he returned to the U.S. he began touring again. A gross amount of lavish spending left Armstrong short of cash and several breach of contract violations plagued him. Finally, he hired a new manager who began to straighten out his legal entanglements. He also began to experience problems with his fingers and lips, a result of his unorthodox playing style. Branching out in other areas, Armstrong modified his vocal style to accommodate theatrical appearances and radio, appearing in “Pennies from Heaven” and on the CBS radio network respectively. He was the first African American to host a sponsored, national broadcast. He finally divorced Lil and married longtime girlfriend Alpha.

Armstrong finally settled in Queens, New York in 1943 with his fourth wife, Lucille. During the next 28 years, he played more than three hundred gigs a year. Starting around the 1940s, especially after World War II, there were a whole new set of demographic, migratory and cultural changes in the country and as a result, big bands tapered off, big ballrooms closed, the advent of television further shifted overall entertainment. Other types of music genres appeared on the scene and big bands were impossible to maintain under those circumstances. Armstrong continued making records and appeared in over thirty films. He became the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time Magazine in February 1949.

In 1964, Armstrong recorded his biggest-selling record, “Hello, Dolly!” At 63, he was the oldest person to make it to Number One on the pop chart, dislodging the Beatles – who had held that position for 14 consecutive weeks – from the Number One position. He then toured Africa, Europe, and Asia under sponsorship of the US State Department with great success, earning the nickname “Ambassador Satch,” though failing health restricted his hectic schedule as his years advanced.

Armstrong was criticized for accepting the title of “King of The Zulus” — in the New Orleans African-American community, an honored role as head of leading Black Carnival Krewe. Some saw him as trying too hard to appeal to White audiences and becoming a minstrel caricature. Others criticized him for playing in front of segregated audiences, and for not taking a strong enough stand in the civil rights movement. However, Armstrong was a major financial supporter of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists, though he preferred to work quietly in the background not mixing politics with his work. But he did break that rule when he criticized President Eisenhower, calling him “two-faced” and “gutless” because of his hesitation to act during the conflict about school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. It made national news. Armstrong canceled a planned tour of the Soviet Union on behalf of the State Department as a protest. He said, “The way they’re treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell.” That placed him on the FBI watch list; they began keeping a file on him for his outspokenness about integration.

He had many hit records including “Stardust,” “What a Wonderful World,” “When The Saints Go Marching In,” “Dream a Little Dream of Me,” “‘Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “You Rascal You,” and “Stompin’ at the Savoy.” One of his biggest hits was “We Have All the Time in the World,” featured on the soundtrack of the James Bond film “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service,” in 1968. Armstrong enjoyed renewed popularity after its release in the UK.

According to the record, Armstrong did not have any children. He died of a heart attack in July 1971, a month before his 70th birthday. He was buried in Flushing Cemetery, New York City in a funeral as lavish as he lived. In attendance, as pallbearers were the governor and mayor of New York state and city; and a multitude of persons from the entertainment community including Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Pearl Bailey and Count Basie.

Armstrong has a record star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on Hollywood Boulevard; he received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1972 by the Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences posthumously; the house in Queens, N.Y. where he lived for 28 years was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977 and is now a museum; in 2001, New Orleans’s airport was renamed Louis Armstrong International Airport in his honor; and the main stadium for the US Open tennis tournament, located a few blocks from where he lived, was named Louis Armstrong Stadium.