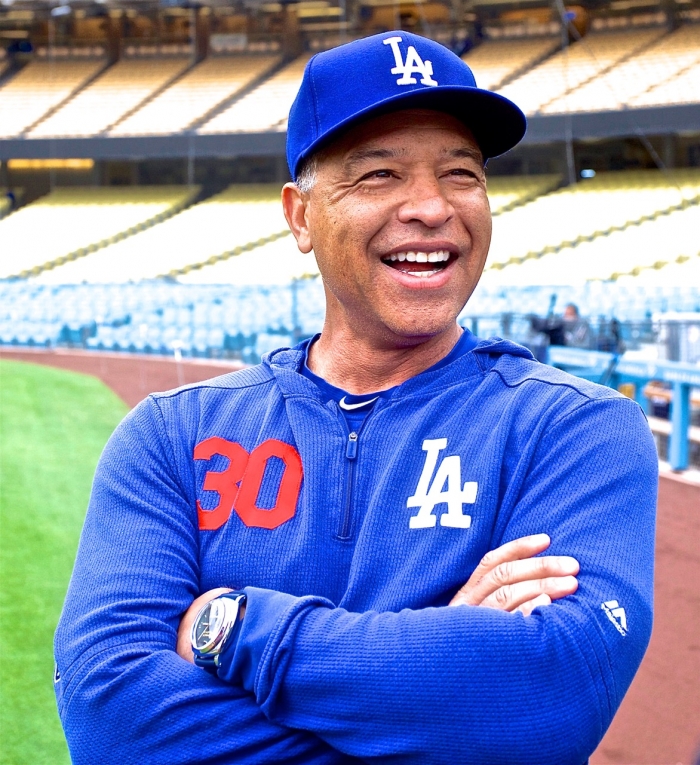

In a sport that has historically marginalized Black players, African American baseball fans have taken great pride in the accomplishments of legendary ball-players like Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby and Willie Mays. When Dave Roberts was named manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2015, he understood that he too would carry a similar legacy.

“It’s hard for me to put into words what it means to be named manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers,” Roberts told MLB.com in 2015. “This is truly the opportunity of a lifetime. The Dodgers are the ground-breaking franchise of Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Sandy Koufax, Maury Wills, Fernando Valenzuela and Hideo Nomo.”

“I feel that I have now come full circle in my career and there is plenty of unfinished business left in L.A.,” said the former Dodger outfielder, who went on to be named 2018 National League Manager of the Year.

As the first African American manager of the Dodgers, Roberts walks in the footsteps of many Black trailblazers in baseball at a time when the African American population in the MLB is at a low with about eight percent of African American players. According to USA Today Sports, there are 11 teams that don’t have more than a single African American player on their 25-man roster, including three teams that don’t have one. There are only three African American players on active rosters in the entire National League West.

Roberts was born in Okinawa, Japan to an African American father, a U.S. Marine, who met his Japanese mother while stationed in Japan. Growing up in San Diego, CA, Roberts says he was fortunate to have a dual heritage. He always embraced both facets of his ethnicity and now he stands as a role model for both Asian American and African American baseball fans.

Beyond the social responsibility that comes along with being a sports figure, comes the labor-intensive job itself. Roberts came on as manager to one of the top-five highest-paid franchises in the MLB. After losing in last year’s World Series, Roberts faced criticism from frustrated fans, including President Donald Trump, who took to his Twitter account to complain about Roberts’ decisions during Game 4 of the World Series.

Still, Roberts’ leadership led the team to compete in two consecutive World Series and the team is well on their way to the third.

“It’s something I really believe in because I think as a young coach or manager, it’s natural to chase results and understand that you’re being judged on results,” Roberts told ESPN. “But to really trust in the process, and getting people to do things the right way, and betting on the results in the back end, I think, is a more attainable goal.”

Following some roster changes this season, the Dodgers are currently in first place and hold a 10 ½ game lead in the National League West.

As a player, Roberts’ most defining moment came in 2004, known as “the most famous steal in Boston Red Sox history,” boosting the team into a comeback against the New York Yankees that won them their first World Series in 86 years. Now what defines Roberts’ career is his philosophy as a leader, his faith in God, the love for his family, and of course, his love for baseball.

It was a sunny Los Angeles afternoon when Roberts sat down with the Sentinel. We met in his office — the L.A. Dodgers’ dugout — just hours before he led his team to beat the Washington Nationals 5-0.

The following is an edited version of the sit-down interview.

Los Angeles Sentinel: There have been a few transitions this year. Tell us what we can expect this year from the Dodgers.

Dave Roberts: For me, for the Dodgers, the last couple years, we lost in the World Series so we were the second-best team in all of baseball. I think that if you look around the industry we’ve done a lot of good things. We are in a great city, great fans, we draw more fans than anyone in all of sports, and as far as an organization, we win. The goal is to bring a championship back to Los Angeles. We made a few tweaks with our roster. Every year you always try to tweak and get that right form. But as far as our culture, we have guys that are blue-collar, who love to play, love to compete, and as a fan when you come watch the Dodgers play, you can relate to them because it’s a group of guys that play hard and play the game and respect the game. I try to understand and let the players understand the vision of winning a championship. The hard part though is the day-to-day grind. And that’s where I am right now just trying to go out there every day and win a baseball game.

LAS: Let’s talk about that grind. How do you approach everyday — like, let’s talk about today, game day — how do you wake up and get your day going?

DR: Today was a special day for me actually, thank you for asking, I had a chance to go to the City of Hope. I am a cancer survivor myself. I went there and they had there 43rd annual Celebration of Life reunion for bone transplant survivors. So, I went there and spoke and got to see families and patients. There was close to 1,000 people there.

LAS: Speaking of such positive energy, is it hard for you to keep your cool when you are having a bad day? How do you navigate that?

DR: In baseball, it’s kind of an outlet. I have grown to understand from the coaches and players that mentored me when I was a player, that when we come to the ballpark, it’s our escape. If I do have a bad day, I don’t let that be known. It is hard though because I’m always trying to pour into the players and coaches and you don’t really get that reciprocation but that’s kind of the job you sign up for. I love coaching, I love teaching and I love relationships, and that is my fuel and that’s my passion.

LAS: Does being a former player help you relate more?

DR: That’s the first piece of advice. You got to remember how hard the game is. So, I think that is one thing that makes coaches and players’ managers understand that these guys are the best at what they do in whatever sport, football, basketball, or baseball, and the game is difficult. They are pros and to be sympathetic towards that and being able to communicate lends itself to being a players’ manager.

LAS: Did you know as a player that you wanted to be a coach?

DR: Absolutely not. It kind of just happened. It’s one of those things in life you just take what’s ahead of you and you try to dominate. So, when I went to UCLA, I adjusted. I was born in Okinawa, Japan. My dad was raised in Houston, one of eight children, he was in the 5th Ward so he grew up the eldest, was on his own in the service at 18. This man was my rock. He loved me with tough love and he supported me. He served our country for 30 years.

Being biracial with an African American father and a Japanese mother, as you’re growing up and moving around to different countries, different bases, different states, you’re always moving. They really empowered my sister and me to be ourselves. I’ve been fortunate that I have two backgrounds to make me who I am.

LAS: Yes, you’re the first African American to coach the Dodgers, and the first Asian American to make it to the World Series. Do you think of that often?

DR: In the forefront of my mind, I don’t. I’m more mired in my job each day and I’m very micro-focused on what I’m doing every day. So, when you say it in that context, it just blows me away.

LAS: So, it’s a reminder. And it’s phenomenal. You are a trailblazer.

DR: When you talk about trailblazers, there’s obviously no one bigger than Jackie Robinson for me. To walk in his shoes and to be mentioned like that as a trailblazer, everyday people say I’m making history. I don’t see it like that I’m just trying to do the best job I can. I feel very grateful to be wearing this uniform.

LAS: In your words, what do you have to say about Jackie Robinson’s legacy?

DR: It is a legacy. My kids joke with me because I use that word a lot. I just believe so strongly in that word, legacy. It’s ongoing, it’s generational but it also takes people to follow what he implemented in his legacy go keep it going.

I look at it as a responsibility. Then I look at Jackie and how tough he was and the stories I hear about him. He knew when to be tough, he knew when to turn the cheek and he knew when to submit, but in the right context, and it just takes a really strong man.

LAS: We are seeing a decline in attendance and representation of African Americans in the MLB? What do you have to say about that and the ways we can change that?

DR: It is true. If you look at the overarching numbers of African Americans in baseball, even since when I first got into the big leagues, its tumbled considerably. It’s unfortunate. I think that a lot of young African American kids in the inner-city are gravitating towards football and basketball. The role models in baseball are starting to be less and less. So, now, as an African American kid, to look at somebody and to relate to them and aspire to be them, those are harder to come by. So, as a sport, with our commissioner [Robert Manfred], I serve on the diversity committee and I am proud of that. We are trying to create opportunities for minorities and African Americans in baseball as athletes as players, in front office coaching and all these different scouts.

The Dodger Dreamfields – we just built the Jackie Robinson field with Adrian Gonzales and Clayton Kershaw, the RBI foundation —we’ve done so many things like that.

For me to be a vehicle, I look for opportunities to go into the city and speak to people of color and just know that there are other sports than football and basketball. But, I think for all of us, it’s about painting a picture that African-American kids are going to be productive in society and be successful and to find a passion.

LAS: I know family and faith are important to you. Can you talk about your faith?

DR: I think my faith in Jesus Christ is the foundation of who I am. Everyone has their thoughts, beliefs and faith, but for my household this is what we believe in. It makes it easier when you have something to hold on to. With life’s struggles and the unknown, that blind faith is tough for a lot of people. People wonder how I can come in positive every day and don’t sweat the small stuff, through cancer and going through different adversities — that’s how. I’ve got a wife of 22 years and my daughter who is fantastic. We are a tight knit group and without those two things I don’t know where I’d be.

LAS: Speaking of legacy, let’s talk about your son.

DR: Yes! He’s going to be a baseball player at Loyola next year. He’s definitely different than me. He’s more subdued but he’s got a heart of gold and he’s a tough competitor. It’s fun to see my son make his own path and be his own individual.

LAS: Can you talk about your battle with cancer? Any advice for people out there who are suffering?

DR: I had Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. It was stage two, there are four stages so it wasn’t in my blood yet and it wasn’t below my diaphragm. So, that’s the good thing. It was fast moving but my oncologist, my radiologist and everyone was on top of it. Obviously, when you hear cancer, it’s a tough word. That “C word” gets people. People equate that to death, but it went back to my faith, my family and my doctors. My wife, my family, my friends, the fans were there supporting me. We didn’t waver and we knew it was happening for a reason. I never felt sorry for myself. My dad, my mom, my father-in-law came to know Christ because of it because of our stead-fastness.

LAS: What is some advice you have for young players?

DR: Don’t ever lose that confidence and out-work people. For me, I was a person that played with a lot of people that were a lot more talented than I was, but I just took pride in outworking them and being educated as far as understanding the game and playing the game hard and the right way.

LAS: What would you like your legacy to be?

DR: I respect the game and I respect people. I think that covers a lot of it. The fans pay big money to watch professional athletes play. How you perform, how you prepare, how you treat fans, how you treat ushers and stadium ops with respect – I think that’s important. As a manager of the Dodgers, I’m on TV and as one of the faces of the organization. To carry myself in the right way is important. I ask for respect and I think the way I treat people in uniform or outside of uniform draws them closer to me and the organization. So, I like to think I’ve done things the right way.

Lauren Floyd contributed to this article

Additional photos