Tinashe Kajese-Bolden said that when she first encountered A.K. Payne’s “Furlough’s Paradise,” she hadn’t just read a script—she had stepped into a world that tested the boundaries of storytelling.

“I met AK’s work before I met AK,” she said. “It looked like word art on the page, and it immediately told me we are testing boundaries by telling this story.”

Payne, a playwright, and abolitionist focused on dismantling the prison-industrial complex, said that “Furlough’s Paradise” was more than a play—it was an act of witnessing.

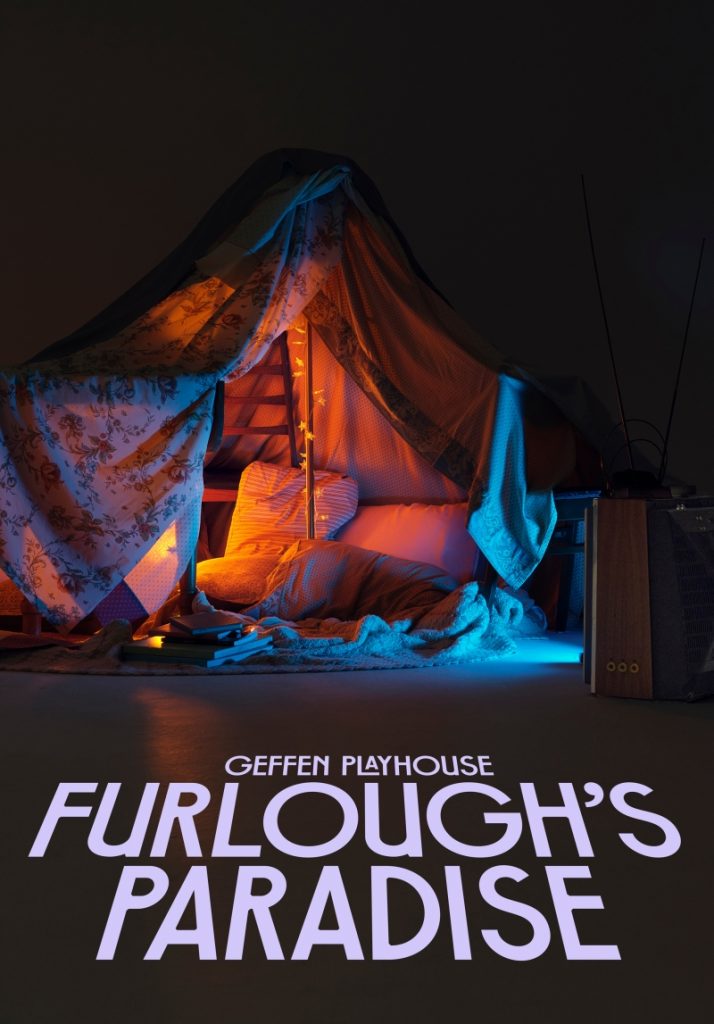

The play, set to premiere at the Geffen Playhouse, follows Sade, who is on a three-day furlough from prison, and her cousin Mina, who is grappling with her own sense of entrapment despite being free. The production will run from April 16 to May 18, 2025.

Related Stories

Amber Ruffin to Host 16th Annual AAFCA Awards

Sterling K. Brown Leads Suspenseful New Series ‘Paradise’

Kajese-Bolden, the Artistic Director of Alliance Theatre, said she saw the collaboration as an invitation into a world of possibility. “AK collapses time,” she said. “Both forward and backward, and as a director, that is such a beautiful invitation—to go places neither one of us had traveled before.” Payne described the play as a lyrical journey about grief, home, and survival.

Payne said language itself was a site of resistance, particularly because of its limitations. “I’m always curious about the limits of English as a structure,” she said.

“It’s a colonial language that cannot hold all that these characters are, so they stretch it, push against it—because they need more.” Kajese-Bolden said that tension is reflected in the play’s movement as well.

“So much of our natural movement has been contained, muted, and distorted into something society will accept,” Kajese-Bolden said.

“The invitation is to ask, ‘Who are we when we are uninterrupted? What does the body do when we allow ourselves full expression?’”

Payne said that music plays a vital role in “Furlough’s Paradise,” acting as a bridge between memory and action.

She described music as almost a second language for the characters, emphasizing that Sade remembers her mother through the songs she played while braiding her hair. Mina’s father is always on the porch listening to jazz.

“Every character has a soundtrack,” Payne said, while Kajese-Bolden explained that sound helps the play navigate its shifting timelines.

“At its heart, ‘Furlough’s Paradise’ is about witnessing,” Kajese-Bolden said. “It’s about seeing someone fully and allowing them to be seen.”

Kajese-Bolden reflected on one of the play’s most powerful moments when Mina, terrified of her own vulnerability, dares Sade to reject her.

“She says, ‘How can I hate myself?’” Kajese-Bolden recalled, explaining how deeply the characters hold each other.

Payne said that connection is the foundation of the play. “I think about this piece as asking, ‘How do people learn to grieve at the end of the world?’” she said.

“For these characters, everything before them has been lost. So, what does it mean to create a grief ritual when there’s nothing left?” She hoped the play would allow space to imagine beyond survival.

Kajese-Bolden said she believed people would come in expecting a play about confinement, but she wanted them to leave with a deeper understanding of freedom. “So often, we’re only given enough room to exist in resistance,” Payne said.

“But what does it mean to imagine beyond that?” They both hoped the play would push audiences to question their own narratives.

When asked to describe “Furlough’s Paradise” in one word, both struggled to condense its vast emotional scope. “Exhale,” Kajese-Bolden said.

“When we exhale, we release something. It’s delicate, we take it for granted, but it’s also survival.” Payne chose two words: “Earth and paradise,” explaining that the play exists in the tension between them.

“They’re trying to figure out how to exist in the middle and bring both parts of those things together,” Payne said.

As the conversation ended, Kajese-Bolden said that “Furlough’s Paradise” was more than just a production—it was an experiment in how theater could create space, redefine freedom, and make room for new possibilities.

“This is a love story,” she said. “A non-traditional love story, but one born in the cracks and folds where love doesn’t usually belong.”