Harry Belafonte made history in early 1968. But it was lost to history.

While the Vietnam War was raging and civil unrest was convulsing American cities, TV talk show host Johnny Carson did something special: He stepped away from “The Tonight Show” perch for a week.

Then something even more special happened: Belafonte took over.

For five nights, the Black singer, actor and activist entertained White middle America with his cool wit and an astonishing array of guests — the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Sidney Poitier, Robert F. Kennedy, Paul Newman, Dionne Warwick, Aretha Franklin, Petula Clark, Bill Cosby, Diahann Carroll and Lena Horne, among others.

That fascinating week of late night is the subject of the new Peacock documentary “The Sit-In,” which airs Thursday and celebrates Belafonte’s strategic and profound mix of art and politics.

“His goal was to show exactly the ease in which African Americans and whites could be with each other and get along,” director Yoruba Richen tells The Associated Press.

The filmmakers initially faced a terrible roadblock: The record of that week is mostly gone. In order to save money, NBC taped over old episodes to film new ones.

All Richen had to work with was interviews with King and Kennedy and a song by blacklisted singer Leon Bibb. Later, she managed to track down some scattered audio recordings.

“When we started, it was a little bit discouraging,” says producer Joan Walsh. “We just made it our mission to kind of create the feeling of the times.”

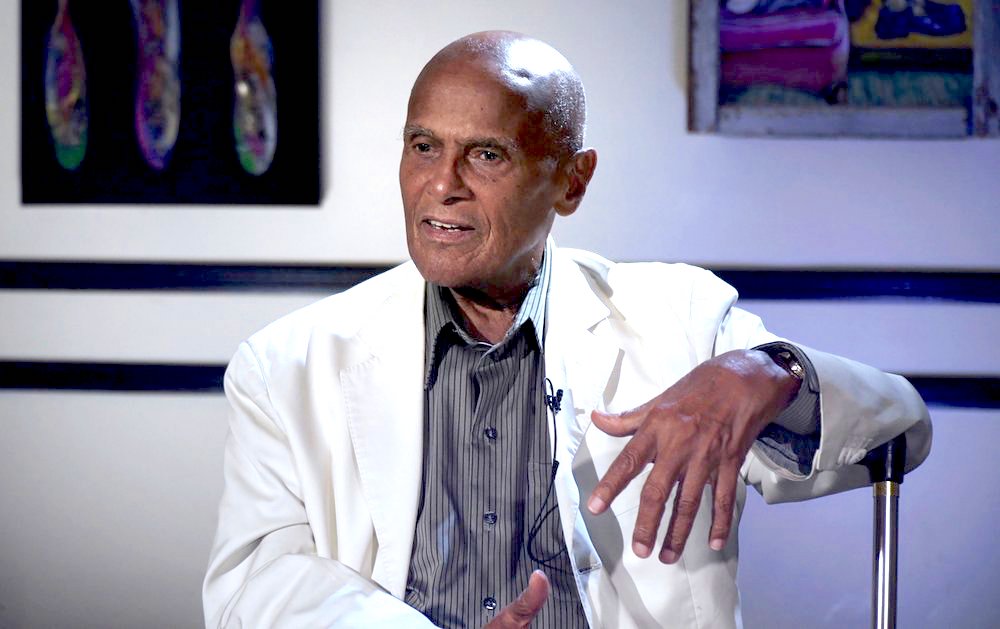

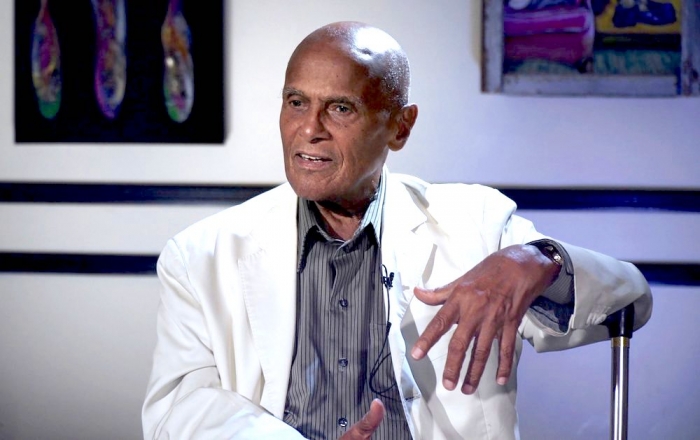

Interviews with as many surviving guests as possible, archival footage and several hours sitting down with the 93-year-old Belafonte helped fill in the gaps, offering a fascinating look at a special time on TV.

In addition to his high-powered guests, Belafonte showed home movies of his family water-skiing and boating — conscious efforts to connect with his white audience.

“He was showing us his life,” says Walsh. “It went a long way to kind of normalize Black middle class and Black upper middle class life.”

The film suggest that Carson knew he wasn’t really able to discuss the racial divide and divisive arguments about the war so endorsed Belafonte, a huge star who could appeal to both Blacks and whites in a time of segregation.

“Johnny saw that that was the right thing to do and did it at a time when not very many people would do anything that brave,” Walsh says.

Walsh notes that Belafonte’s guest-host duties foreshadowed the current #ShareTheMicNow campaign, in which white people hand over their social media accounts to people of color to amplify Black voices. “I wish somebody would do something like it today,” Walsh says.

Though footage of those five nights is spotty, the experience was part of Belafonte’s memoir “My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance.” Says Walsh: “It was hiding in plain sight.”

The impact of Belafonte’s cheekily so-called “sit-in” is hard to measure but many believe it had profound effect. “That was probably the most revolutionary move that mainstream television could have done at the time,” Questlove says in the documentary.

One person watching was a young Henry Louis Gates Jr. The literary scholar would later write in the New Yorker: “Night after night, my father and I stayed up late to watch a black man host the highest-rated show in its time slot — history in the making.”

The “Sit-In” filmmakers hope some lessons can be learned from the 52-year-old late night switch. Richen notes that talk shows these days are still very male and white.

“We still don’t have adequate representation on late night. Late night is really important because that’s where so many people get their news — understand the events of the day, understand politics — and there is a need to have more diverse voices.”