The National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) has launched a global news feature series on the history, contemporary realities and implications of the transatlantic slave trade. This is Part 9 in the series.

(Read the entire series: Slavery Part 1, Slavery Part 2, Slavery Part 3, Slavery Part 4, Slavery Part 5, Slavery Part 6, Slavery Part 7, Part 8)

“Impossible is just a big word thrown around by small men who find it easier to live in the world they’ve been given than to explore the power they have to change it. Impossible is not a fact. It’s an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It’s a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.” — Muhammad Ali

“We need to exert ourselves that much more, and break out of the vicious cycle of dependence imposed on us by the financially powerful: those in command of immense market power and those who dare to fashion the world in their own image.” — Nelson Mandela

The most enduring consequences of the migration for the migrants themselves and for the receiving communities, were the development of racism and the corresponding emergence and sustenance of an African-American community, with particular cultural manifestations, attitudes, and expressions.

The legacy is reflected in music and art, with a significant influence on religion, cuisine, and language, according to Paul E. Lovejoy, a distinguished research professor and Canada Research Chair in African Diaspora History at York University in Toronto.

“The cultural and religious impact of this African immigration shows that migrations involve more than people; they also involve the culture of those people,” Lovejoy said in a recent post about the creation of the African diaspora.

American culture is not European or African but its own form, created in a political and economic context of inequality and oppression in which diverse ethnic and cultural influences both European and African – and in some contexts, Native American – can be discerned, Lovejoy said.

“Undoubtedly, the transatlantic slave trade was the defining migration that shaped the African Diaspora. It did so through the people it forced to migrate, and especially the women who were to give birth to the children who formed the new African-American population,” he said.

These women included many who can be identified as Igbo or Ibibio but almost none who were Yoruba, Fon, or Hausa.

Bantu women, from matrilineal societies, also constituted a considerable portion of the African immigrants, and it appears that females from Sierra Leone and other parts of the Upper Guinea Coast were also well represented, Lovejoy said.

“These were the women who gave birth to African-American culture and society,” he said.

After many rang in 2019 with celebratory parties and gatherings, there were still others who solemnly recalled the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade that started 400 years ago – 500 years, depending upon the region.

For Africans throughout the diaspora, their struggle not only traces back 400 or 500 years, but it continued and was underscored as recently as 135 years ago when the infamous Berlin Conference was held.

The conference led to the so-called “Scramble for Africa” by European powers who successfully split the continent into 53 countries, assuring a division that remains today.

“There isn’t a single thing that was more damaging to Africa than the Berlin Conference,” said African Union Ambassador Dr. Arikana Chihombori-Quao.

“Africans weren’t even invited to the conference,” she said.

At the conference, which took place over three months in Brazil beginning in February 1884 and attended by 13 European nations and the United Sates, ground rules were established to split Africa.

“Africans still are suffering the consequences,” the ambassador said.

Said John W. Ashe, the president of the United Nations General Assembly:

“The Transatlantic slave trade … for 400 years deprived Africa of its lifeblood for centuries and transformed the world forever.”

There’s no question that legacies of the slave trade persist today in most of the countries Africans were taken to, said Ayo Sopitan, founder of Pendulum Technologies in Houston, Texas.

“I have been thinking about how Africans and the diaspora need to get together – through proxies in the persons of recognized leaders – and have a conversation about the past, the role that African collaborators played and how we can unite as a people. Then, and only then will we be able to excel as a people,” Sopitan said.

“I have sat at lectures by Henry Gates and learned about blacks in the Americas. The conclusion is that wherever we are, blacks are usually at the bottom of the totem pole. This does not have to continue,” he said.

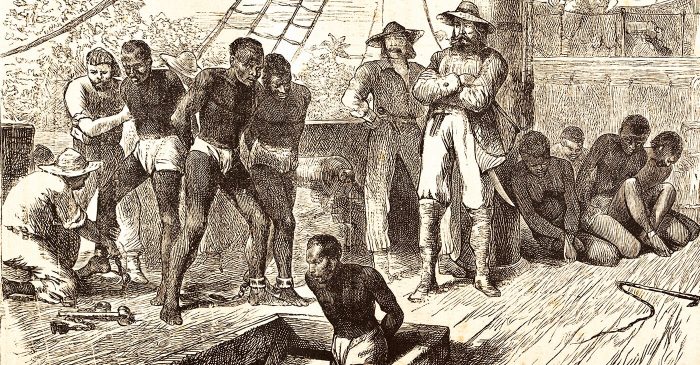

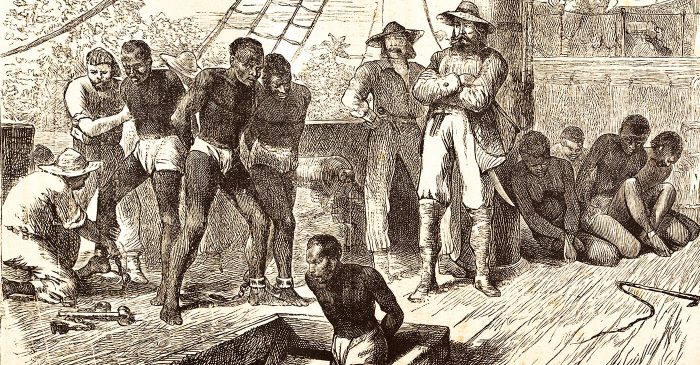

The transatlantic slave trade was an oceanic trade in African men, women, and children which lasted from the mid-sixteenth century until the 1860s.

European traders loaded African captives at dozens of points on the African coast, from Senegambia to Angola and round the Cape to Mozambique.

The great majority of captives were collected from West and Central Africa and from Angola, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization – UNESCO.

The trade was initiated by the Portuguese and Spanish especially after the settlement of sugar plantations in the Americas, UNESCO officials noted in a 2018 web presentation titled, “Slavery and Remembrance.”

European planters spread sugar, cultivated by enslaved Africans on plantations in Brazil, and later Barbados, throughout the Caribbean.

In time, planters sought to grow other profitable crops, such as tobacco, rice, coffee, cocoa, and cotton, with European indentured laborers as well as African and Indian slave laborers.

Nearly 70 percent of all African laborers in the Americas worked on plantations that grew sugar cane and produced sugar, rum, molasses, and other byproducts for export to Europe, North America, and elsewhere in the Atlantic world, according to UNESCO.

Before the first Africans arrived in British North America in 1619, more than half a million African captives had already been transported and enslaved in Brazil.

By the end of the nineteenth century, that number had risen to more than 4 million.

Northern European powers soon followed Portugal and Spain into the transatlantic slave trade.

The majority of African captives were carried by the Portuguese, Brazilians, the British, French, and Dutch. British slave traders alone transported 3.5 million Africans to the Americas, UNESCO reported.

The transatlantic slave trade was complex and varied considerably over time and place, but it had far-reaching and lasting consequences for much of Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia.

The profits gained by Americans and Europeans from the slave trade and slavery made possible the development of economic and political growth in major regions of the Americas and Europe.

Europeans used various methods to organize the Atlantic trade.

Spain licensed (by Asiento agreements) other nations to supply its Spanish American and Caribbean colonies with African captives. France, the Netherlands, and England initially used monopoly companies.

In time, the demand for African laborers in the Americas was met by more open trade which allowed other merchants to engage in the trade with Africans.

Thus, formidable private trading companies emerged, such as Britain’s Royal African Company (1660–1752) and the Dutch West India Company of the Netherlands (1602–1792), according to UNESCO.

The profits generated from the Atlantic trade economically and politically transformed Liverpool and Bristol in England, Nantes and Bordeaux in France, Lisbon in Portugal, Rio de Janeiro and Salvador de Bahia in Brazil, and Newport, Rhode Island, in the United States.

Each port developed links to a wide hinterland for local and international goods in Asia and capital to sustain the trade in African captives.

European merchants and ship captains – followed later by those from Brazil and North America – packed their sailing vessels with local goods and commodities from Asia to trade on the African coast.

Enslaved Africans, their often-violent capture and enslavement out of sight of the European general public, were exchanged for iron bars and textiles, luxury goods, cowrie shells, liquor, firearms, and other products that varied region by region over time.

Much of the wealth generated by the transatlantic slave trade supported the creation of industries and institutions in modern North America and Europe.

To an equal degree, profits from slave trading and slave-generated products funded the creation of fine art, decorative arts, and architecture that continues to inform aesthetics today, UNESCO officials said.

“European countries – Portuguese, English, French, and Spanish – are most complicit in the transatlantic slave trade. This pernicious form of slavery was driven by European capitalistic countries seeking to expand their nation-states and empires,” said Dr. Jonathan Chism, assistant professor of history and a fellow with the Center for Critical Race Studies at the University of Houston Downtown.

The hurt continues today.

“The fact that slavery was underway for a century in South America before introduction in North America is not widely taught nor commonly understood,” said Felicia Davis of the HBCU Green Fund.

“It is a powerful historical fact missing from our understanding of slavery, its magnitude and global impact. Knowledge that slavery was underway for a century [before it began in North America] provides deep insight into how enslaved Africans adapted,” Davis said.

She continued:

“Far beyond the horrific seasoning description, clearly generations had been born into slavery long before introduction in North America. It deepens the understanding of how vast majorities could be oppressed in such an extreme manner for such a long period of time,” Davis said.

“It is also a testament to the strength and drive among people of African descent to live free.”