Like every small town in America, Collierville sent young men off to World War II and collected scrap tin. But its people, including African-Americans _ whose lives are missing from newspaper accounts of the early 1940s _ sacrificed in ways now almost lost to history.

For the past three months, it’s been up to juniors in Dr. Marianne Leung’s U.S. history class at St. George’s Independent School in Collierville to find the fragments of valor and the primary sources to flesh out the details.

Their work _ a textured, personal odyssey through the war years most had only read about _ opens tonight in the Morton Museum of Collierville History with 12 curated panels of narrative, photography and memorabilia.

“It’s kind of surreal that small towns had as big an impact on World War II as they did,” Chloe Booth, 17, said. “No one thought that going into this.”

They found a “tractorette” class, initially an effort introduced by International Harvester Co. to address the farm labor shortage created by war mobilization, was offered for women in Collierville. A team interested in fashion learned that war efforts limited the number of pleats in women’s skirts to save fabric.

Another found proof that while President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802 prohibited racial discrimination in war industries, only white women were allowed to apply for jobs in a shell (ammunition) loading plant opening in Cordova.

All 64 students in three sections of U.S. history chose an aspect of life during the war and dug into digital archives of The Collierville Herald owned by the museum to find the context and begin hunting down sources.

For some, the work had a steady, even pace. Ben Stamps, 16, a fifth-generation Collierville resident, has grown up hearing the stories of the town’s history. Some of the exhibit’s memorabilia, including a military uniform, came from his grandparents’ home.

“To see what it was and how it contributed to the war effort through the schools, the people who went to war and the people at home, was interesting. I was seeing it from the perspective of a viewer,” he said.

“We struck gold mines at times. We’d get a name and call them up, and they’d give us all this information,” Stamps said. Students unearthing the contributions of African-Americans looked blankly at Census pages, hoping to see something they had missed the day before.

“There was nothing. The people there had either died or moved,” said Makayla Smith, 16. “We asked Dr. Leung. She didn’t know.”

As a stab in the dark, Smith and Noah Pope, 17, reached out to Edith Caywood, daughter of Lucius Burch, an attorney who worked on behalf of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to have the U.S. District Court injunction lifted against a march to support the sanitation workers in 1968. The two later found Thomas Brown, an African-American resident who was a child in Collierville when the U.S. joined the war.

“He told us that black families collected cans and bought war bonds. But he also said, `We didn’t have the resources that white kids did.’ Most African-American households didn’t have radios. They didn’t know much about the war. When they signed up to fight, they didn’t know where they were going; they just knew they were going off to fight for their country,” Pope said.

According to 1940 Census, African-Americans represented a third of Collierville’s population. But because the details of their lives _ beyond lynchings and details in crime blotters _ are missing from newspaper accounts, one of the students’ most-used primary sources, “You would think they didn’t do anything,” Pope said.

A panel in the exhibit notes the black community, under the leadership of O.L. Armour and his wife, Minnie, gave $18 in a Red Cross drive in November 1941, “with the meager incomes at the time, this was quite a contribution.”

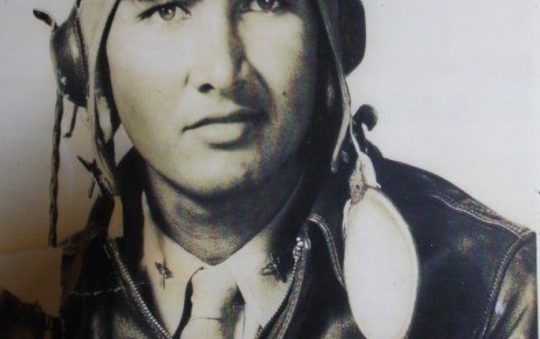

The work also turned up details of the efforts of the women of Collierville, including identifying Nina Stamps, who the class thinks may be the town’s lone WAVES (Women Accepted to Volunteer Emergency Service). Her descendants in California sent her dogtags for the exhibit.

“One of our points is we don’t historically know much about small communities in the United States because it is hard work,” Leung said. “When you have to spend a day and half to get this much information,” she said pinching her finger and thumb together, “it’s so easy to go the other way and focus on urban areas.

“If you want to reconstruct what happened, you have to be more creative. We could read The Collierville Herald and fish for the stories (on what white people were doing.) That was easy.”

The interviews students conducted will be added to the museum’s oral histories on YouTube.

“We are a repository for community history,” said museum director Ashley Carver. “Now, it is a fuller picture, including African-Americans and women.”

The exhibit, which closes May 28, opens with a reception from 5 to 7 p.m.