The recent proposals for reparations coming out of San Francisco clearly remind us that reparations, as a concept, policy and practice, is complex and vulnerable to numerous recommendations without approval or implementation and to performance expressions of concern and acceptance without any concrete action afterwards.

Like the recent summer of anti-racist demonstrations and demands which produced system pronouncements and performances of empathy and understanding with little or no systemic change, reparations has been inserted through struggle in the national discourse, but has not yet reached and received the called for reckoning that would result in public policy and socially sanctioned practice.

The Kawaida conception of reparations is a larger concept, process and practice, requiring: 1) a communal and public dialogue; 2) public admission of the Holocaust of enslavement (Maangamizi); 3) public apology; 4) public recognition; 5) compensation in various forms; 6) preventive measures through radical structural changes; and 7) the earnest and audacious struggle to achieve these goals.

If we are not rightfully attentive to the diversionary and destructive ways and wiles of the oppressor, we will find ourselves denying each other monies we don’t yet have, fostering divisions we clearly don’t need, and undermining the possibilities of an operational unity without which we cannot win this vital and collective struggle. Moreover, as I have argued elsewhere, these unresolved contradictions in the Movement will undermine our call for a national reparations policy and program by engaging us in proposed separate settlements which can’t possibly represent the massive repair our communities need and justly deserve.

The arguments and acceptance of these proposed separate settlements certainly reaffirms the urgent need of our people for cash money and relief from disabling deprivation and suffering. But, they also can induce us to accept less than we deserve, reduce compensation to money, and focus less on the primary injury of the Holocaust of enslavement and its ongoing oppressive impact which gives the demand of reparations its essential moral meaning and moral weight.

Also, if we are not careful in our calculation of what is necessary and needed, we will make money the measure of all things and forget that money is a means not an end and that what is most important is a holistic approach which understands reparations as achieving a wide range of conditions and capacities to live good and meaningful lives and pass on these to future generations. And again, if we are not rightfully attentive, the demand for reparations and the discourse surrounding it can become an artificial substitute for the righteous and relentless struggle necessary to achieve reparations in any expansive sense.

For to talk of reparations in an expansive sense means to speak of the process and practice of healing, repairing, renewing, and remaking ourselves in the process and practice of repairing, renewing and remaking the society which injures and oppresses us. This notion builds on the holistic Kawaida concept of health, wellness and well-being as the absence of disease, injury and impairment, and the presence of physical, emotional, mental and socio-economic conditions and capacities to live a good and meaningful life; fulfill our relational obligations and rightful expectations of our loved ones and respected others; develop our potential; and come into the fullness of ourselves.

It is a fundamental and continuous contention of Kawaida thought that in the midst of the pathology of oppression, there is no reliable remedy except resistance, no strategy worthy of its name that does not privilege and promote struggle, and no way forward except across the bloodstained battlefield for a radically better world. Here in using the word “remedy,” I want to move beyond its English meanings of treatment of a disease or injury and in general, finding a solution. And instead, I want to link remedy with reparations and repair and expand the concept so that it contains and requires the practice of resistance, recovery and a life of health and wholeness.

To do this, I want to bring into conversation the Swahili concept kuponya with its multiple meanings for remedy. For in Swahili, kuponya means to remedy in numerous interrelated ways. These include meanings of to: heal; rescue; deliver as in save; cure; comfort; restore to health; escape and avoid danger; and preserve life.

It is within this expansive and inclusive conception of remedy that I conceive and pose reparations and resistance as inseparable radical remedies for the pathology of oppression. Summing up and centering this rich array of meanings of remedy as a radical practice of both reparations and resistance, I want to interpret its essential meanings as reparative and liberative practices: 1) to preserve life; 2) to treat and cure a disease, illness or injury; and 3) to enhance life.

Here I offer the Kawaida concept that we must understand and assert ourselves as injured physicians who have the capacity to and must repair, renew and remake ourselves in the process and practice of repairing, renewing and remaking society and the world, transforming them into an ever-expanding realm of freedom, justice and human flourishing. This reaffirms our agency, places responsibility for our ultimate repair in our own self-liberating and self-uplifting hands.

And as always when we talk of responsibility, we note its two interrelated dimensions. For the oppressor is responsible for our oppression, but we are responsible for our liberation from that oppression, and a key part of our responsibility is holding the oppressor responsible for his oppression of us. And there is no way to hold an oppressor responsible except through struggle against his oppression in all its savage and subtle forms.

Indeed, reparations is about achieving justice for the injured and oppressed, extracting accountability from the oppressor, and through this righteous, relentless and liberating struggle repairing, renewing and remaking ourselves and the world.

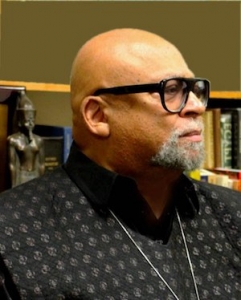

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.