As we commemorate the 1963 March on Washington, if we remember and reason rightly about our most massive marches in Washington, the threatened “thundering March” on Washington in 1941, the March on Washington in 1963, and the Million Man March in 1995, we realize that they have similar and interlocking lessons, aims and aspirations rooted in our centuries-old and ongoing righteous struggle for freedom as a people.

In a word, all were and are a part of the awesome history and hard-rock struggle of the Black Freedom Movement. For at the core and our constant need in all our demands and aspirations is freedom. That is to say, freedom from domination, deprivation and degradation, and freedom to live a good and meaningful life, develop our potential, flourish and come into the fullness of ourselves.

Looking back at these massive organizational and liberational projects, however, we find that they are planned and carried out with multiple motives and meanings, but always with focus still on freedom. For as Nana Haji Malcolm, freedom fighter and noble witness to the world for our people, taught, “freedom is essential to life” and justice and equality can only have substantive meaning and fullness in freedom. Among these reasons, whether for the original march and the commemoration of it, or all the subsequent ones, is first the practice of the morality of remembrance.

Indeed, we marched then and now in memory and reciprocal obligation to those who gave so much, sacrificed and suffered immensely, were jailed, imprisoned, assaulted, battered, shot, and much too-often murdered and martyred fighting for rights they had simply by being human. This morality of remembrance practiced for both the departed and the living is beautifully summed up by our foremother and freedom fighter Nana Fannie Lou Hamer. She tells and teaches us “there are two things we all should care about, never to forget where we came from and always praise the bridges that carried us over.”

We march and commemorate the marches also to uphold and reaffirm a tradition of righteous and relentless struggle, an ethical imperative and enduring struggle to expand and secure the realm of freedom and justice in this country and the world. It is a tradition left to us as a living legacy, a model and mirror by which we mold and measure ourselves. It is a tradition which identifies and defines us to history and humanity as a moral and social vanguard, consciously and irreversibly committed to a society and world of shared and inclusive good.

And it is grounded in and informed by a teaching we know and hold dear, the teaching of our forefather and freedom fighter Nana Frederick Douglass who taught us that “if there no struggle there is no progress,” that “the struggle may be a moral one or it may be a physical one, or it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle.” For “power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Also, our people and our allies march and commemorate to make and reaffirm pressing, priority and ongoing demands intimately and ultimately rooted in and related to our demands for freedom and justice. These demands are demands for conditions and capacities to live lives of dignity, decency and ongoing development. In other words, conditions and capacities of freedom and justice include their right to life, itself, sufficient and nutritious food, safe and clear water, adequate and affordable healthcare and housing, just employment and economic security, a healthy and sustainable environment, and security of person and people.

These dignity-affirming, life-enhancing and world preserving demands and essential goals of our struggle are rooted in an ethical and resistance tradition which is also informed by the ancient African moral imperative that “we must bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place among those who have no voice, the devalued, disempowered, downtrodden, the different and vulnerable. For we measure the moral quality of any society or social and racial justice project by how it respects and treats the most vulnerable among us.”

In the midst of the racist morals and social savagery of segregation, marches and other forms of resistance made clear that the struggle was not only against racist hatred, hostility and self-inflicted fear being turned into public policy and socially sanctioned practice which remains an ongoing focus of concern and resistance. But given the racist targeting and social terrorism directed against us, our liberation struggle has been from the beginning a dual one, a struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves.

It is to be ourselves, African Americans, Black persons and a people without penalty, punishment or oppression, and to free ourselves from the domination, deprivation and degradation imposed on us in various savage subtle, direct and disguised forms.

Finally, we march and commemorate, then and now, to reaffirm our understanding of the compelling presence and urgency of the unfinished struggle for freedom, justice and shared good in society and the world. Indeed, it is not only for a shared good in the world, but also a shared good for the world. In fact, our overall struggle is a combined and simultaneous one, both for human good and the well-being of the world and all in it.

Nana Dr. King, freedom fighter and world witness for our people, is right in asserting that, “All life is interrelated; we are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied to a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”

He speaks here of the global concern and impact of war and peace, but this and his concern for worker safety from hazardous chemicals and polluted air and water made in the support of the Black sanitation workers in Memphis makes an important contribution to our discussion and advocacy for environmental justice.

At the 1963 March on Washington, Nana King tells us and the country, “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on (a) promissory note to us concerning freedom, justice and equality,” giving “the (Black) people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

“But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now.” This centers the urgency of continuing struggle and of reparative justice.

And our honored freedom fighter, Nana Dr. Dorothy Height, uncredited co-planner of the March on Washington 1963 and recognized co-planner of the Million Man March on Washington 1995, sums up our duty and destiny in these difficult, dangerous and demanding times. She tells and teaches us that the gates of freedom have only been opened slightly and that as both persons and a people, “we must always be a strong presence, an unrelenting force working for equality and justice until the freedom gates are fully open.”

In the Million Man March Mission Statement 1995, the organizers reaffirmed our shared commitment to the ongoing liberation struggle, offer public policy demands and aims around issues of freedom, justice and equality, and noted the historical significance of the transformative work we do in the world.

The Mission Statement closes saying: “We stand in Washington conscious that it is a pivotal point from which to speak to the country and the world. And we come bringing the most central views and values of our faith communities, our deepest commitments to our social justice tradition and the struggle it requires, the most instructive lessons of our history, and a profoundly urgent sense of the need for positive and productive action.”

And through this, we rightfully “honor our past, willingly engage our present and self-consciously plan for and welcome our future.”

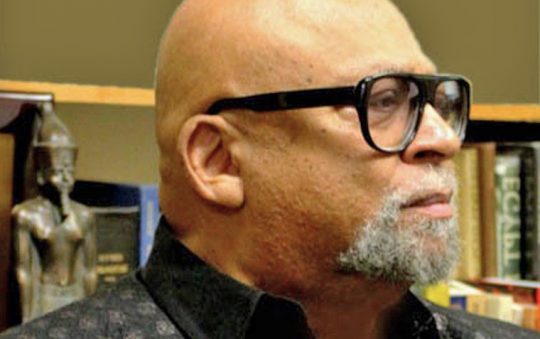

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.