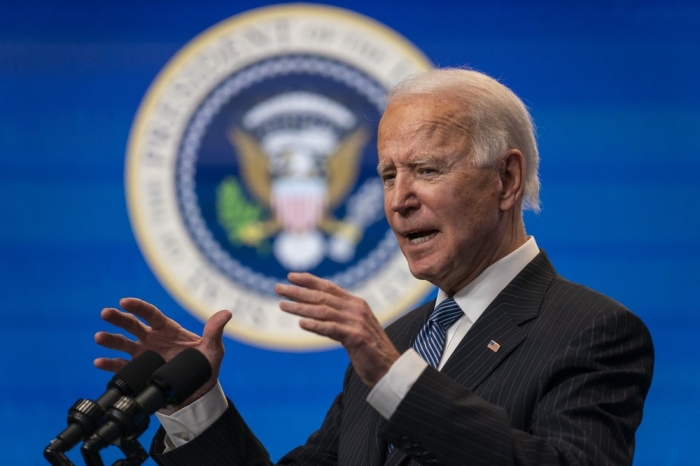

Coming off a successful midterm, President Joe Biden must follow through on a resolution to Black labor in the New Year. Specifically, he has to keep his promise to train and hire skilled workers on an equitable basis for the 700,000 jobs anticipated under the $1.2 trillion infrastructure law, most notably in highway construction.

The failure to do so will result in a replay of the discriminatory outcomes of past infrastructure projects. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black Americans are glaringly under-represented in the vital construction industry, comprising five percent of the workforce compared to their 14 percent of the population. By contrast, about 61 percent of the workforce is white and 30 percent Hispanic. (Moreover, about 25 percent of the workforce are immigrants, legal and illegal.)

Just as the Biden administration must act, Black political and labor leaders should prepare to scrutinize the infrastructure policies of states. Vigilant oversight is the best way to be confident that inclusive hiring provisions are upheld. To date, about 6,000 projects funded by the infrastructure package are quietly underway, and about $185 billion has been distributed to states.

The promise of jobs was made last year when the administration lobbied Congress to support the bill; it made a commitment to train and employ Black skilled labor for the construction trades. In November 2021, after Biden signed the act into law, Congressional Black Caucus Chairwoman Rep. Joyce Beatty (D-OH) informed constituents of the jobs to come.

For example, she recounted a conversation with Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg—whose department allocates funds for highway projects. According to Beatty, she “reached out to talk about diversity and equity in projects” and was assured that it would be a priority of the administration.

Her understanding was reinforced by the former CBC chair and White House senior adviser Cedric Richmond. He described the training and employment for thousands of construction jobs for hard-pressed Black workers bypassed by the industry. The jobs include building roads, weatherizing projects, electrification of bus fleets, and more. “Ninety-four percent of these jobs won’t require a four-year degree,” Richmond added.

To bring more Blacks into the industry will require overcoming racial barriers with deep roots in modern history, according to Travis Watson, the chair of the Boston Employment Commission. Watson leads the agency that oversees employment goals for city construction projects. He described both the appeal of union construction jobs and the methods used to thwart Black skilled workers in a piece for the Stanford Social Innovation Review, titled, “Union Construction’s Racial Equity and Inclusion Charade.”

“Union construction jobs are not just good jobs, they are great jobs,” he wrote, noting that the jobs “have a relatively low entry barrier and offer world-class training, great pay, and benefits that allow members to retire with dignity. However, what’s often overlooked is union construction’s racism, and that those great jobs, particularly leadership positions, are designed to remain filled by white men.”

Five Ways the Law Seeks an Inclusive Construction Industry

The Infrastructure Act includes little-discussed provisions to promote equity in the construction trades. Here are five important ones in a 1,000-page document with many sections of directives. For example, the hiring standards for “Surface Transportation” projects—primarily the federal highways—include the following language:

First, Section 11203 on “State Human Capital Plans” requires the Biden administration to encourage each state to develop a five-year plan “for the immediate and long-term personnel and workforce needs of the state.” Although compliance is voluntary, the state plans have a due date of April 2023, and a copy should be made available to the public.

Second, the state plans should identify ways to broaden the racial and gender composition of the state construction workforce. For example, Section 13007 on “Research, Technology, and Education” calls for “targeted outreach and partnerships” and paid employment opportunities such as “pre-apprenticeships, apprenticeships, and career opportunities for on-the-job training.”

Third, the plans should reflect the language in Section 25019 on “Local Hiring Preference for Construction Jobs.” It addresses the barriers to employment for ex-offenders, people with disabilities, and “individuals that represent populations that are traditionally underrepresented in the workforce.”

Fourth, the state plans should calculate the workforce needs for energy infrastructure and building efficiencies. Section 40513 on “Career Skills Training” seeks ways to identify and recruit workers from “target populations of individuals who would benefit from training” and “achieve economic self-sufficiency.”

Finally, the law calls for the transportation secretary to explore ways to bring women into the trucking industry. Section 23007 on “Promoting Women in the Trucking Workforce” has the following directive: “It is the sense of Congress that the trucking industry should explore every opportunity to encourage and support the pursuit and retention of careers in trucking by women.” It suggests the establishment of a federal “Women of Trucking Advisory Board.”

Black Construction Workers and Remedial Justice for Past Wrongs

Black political and labor leaders may want to weigh the merits of preferential hiring claims as “remedial justification” for historic wrongs. The Biden administration has acknowledged a pattern of racial disparities in past infrastructure programs. Recently, Biden’s infrastructure “czar,” the former New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu, spoke of the need to prevent similar outrages.

However, the administration has been slow to champion remedies for the pattern of discrimination in the highway construction industry. Such activity has kept the Black labor force under-developed, while helping to bolster the white middle class and major construction companies.

Here are some ways that racism has played out under past federal infrastructure initiatives:

Between 1935 and 1943, the federal government initiated an industrial plan to jump start the economy during the great depression. Under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, the government invested $11 billion dollars to put more than 8 million people to work under the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Yet, the WPA projects excluded Blacks from all but the least-skilled and lowest paying construction jobs, despite the promise of the Roosevelt Administration to prohibit race discrimination. As a result, Black workers were paid far less than white skilled tradesmen and the WPA neglected to invest in their training and retention.

In 1956, the federal government embarked on a second infrastructure initiative known as the Federal Highway Act. The postwar industrial plan authorized the construction of 41,000 miles of interstate highways. Over many years, transportation planners routed some highways directly, and sometimes intentionally, through Black communities. In addition, homes were taken through eminent domain—with below-market value compensation to those displaced.

Moreover, the highway projects generated well-paying construction related jobs for white men and contracts for white-owned companies, primarily. Some of the companies that benefited from exclusive highway contracts are still around to compete for infrastructure projects today.

In the 1960s, Black construction workers and contractors had high hopes when President Lyndon Johnson issued Executive Order 11246. It called on the secretary of labor to promote equity in the industry—but the hopes were soon dashed.

Paul King, who owned a Black construction company in Chicago at the time, recalled the period in a 1999 article, titled, “Can You Dig It?: Affirmative Action and African Americans in the Construction Industry.”

He wrote: “On July 23, 1969, I was one of the leaders who shut down Chicago construction sites because of the absence of black workers and contractors in HUD-financed building projects. Hundreds of demonstrators were inspired by Presidential Executive Order 11246, which required contractors on federally assisted construction projects to not only cease discriminating against blacks, but take ‘affirmative action’ to increase African American participation.”

Black Construction Workers and Discrimination Today

Returning to 2022, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reports that Black workers continue to face discrimination in the construction trades. According to Charlotte A. Burrows, chair of the EEOC, “The construction sector has always been an important component of the American economy, as a major employer of America’s workers, a pathway to prosperity and security, and a key indicator of the nation’s health. Unfortunately, many women and people of color have either been shut out of construction jobs or face discrimination.”

Burrows described incidents that included “displays of nooses; threats and physical harassment; and sometimes physical or sexual assaults.” Meanwhile, Travis Watson of the Boston Employment Commission described methods that construction unions have used to exclude Black workers: There is the “Catch 22,” where people are required to have a construction job to join the union, but need union membership to get a job; “Stonewalling,” where a union frustrates an applicant by refusing to communicate; “Biased Gatekeepers,” where union dispatchers bypass Black workers for jobs, and “Discriminatory Testing,” where applicants must pass a subjective test for membership. Finally, “Explicit Racism,” where white workers use racist language and assign Blacks to dangerous situations.

In addition to the obstacles created by employers and unions, Black labor encounters undue competition from immigrant workers—both legal and illegal. Since 2003, Hispanic workers have crowded the field and account for 30 percent of the workforce today, up from 20 percent in 2003. Some contractors favor them as pools of cheap labor.

In closing, the Biden administration has a responsibility to make good on the promise of construction related jobs for Black labor. It can begin by scrutinizing the state plans for highway and energy projects.

Black leaders must be especially vigilant in states with new-found political clout such as Maryland, Georgia, and North Carolina, and in states where their community is key to political success like Virginia, New York, New Jersey, Michigan, and Illinois. All have a role to play to insure the implementation of racially inclusive hiring for the infrastructure of modern America.

Roger House is associate professor of American Studies at Emerson College, Boston. The commentary is reprinted from The Daily Beast.