Streets. Schools. A bridge in Burkina Faso. The name of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. can be found across Africa, a measure of the global influence of the American civil rights leader who was shot dead 50 years ago after speaking out against injustices at home and abroad.

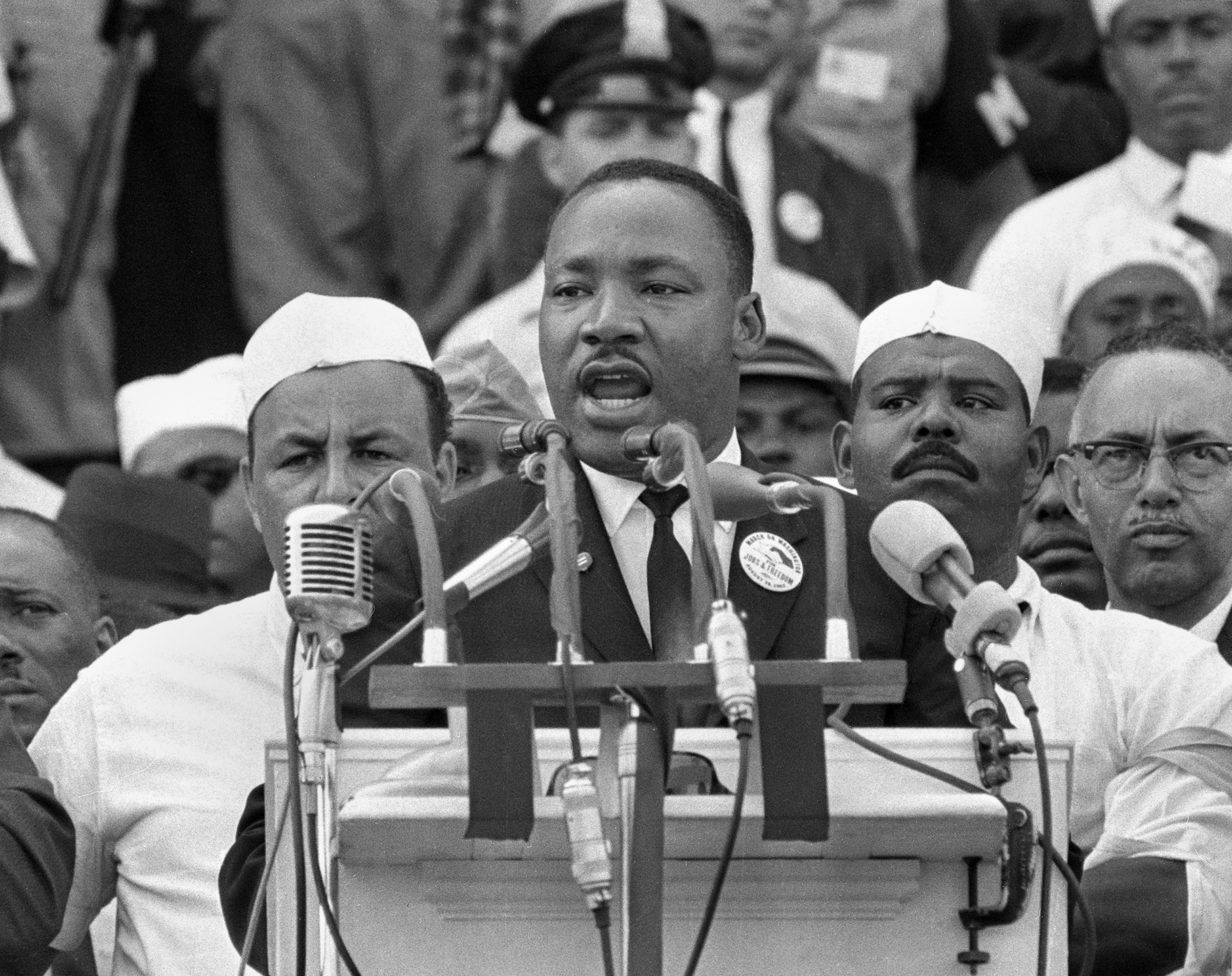

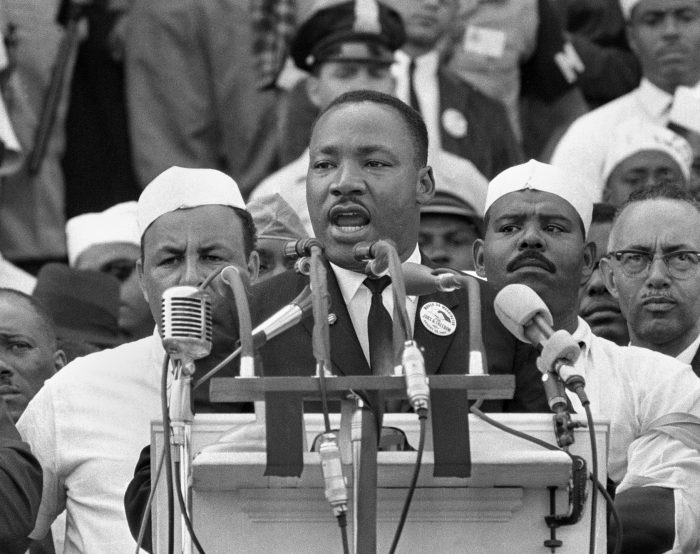

A school for poor children that is named after King in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, took as its motto, “Have a Dream,” borrowing a line from one of King’s most famous speeches.

“Martin Luther King stood for human rights and equality, so we wanted a way of inspiring and motivating our students,” said Robert Mpala, the school’s founder.

In rural Liberia, a West African nation founded by freed American slaves, one official spoke proudly of a privately owned Martin Luther King School. “Martin Luther King was a great man. We still follow his dream,” said J. Maxime Bleetahn, director of communications at the Ministry of Education.

Africa’s push for independence from colonialism, which mirrored King’s own movement for racial equality in America, attracted the civil rights leader’s attention and support.

King first set foot on the continent in March 1957 to attend celebrations marking the West African nation of Ghana’s independence from Britain.

After he returned to Africa in November 1960 to attend the inauguration of Nigeria’s first president, King said African leaders had told him “in no uncertain terms that racism and colonialism must go, for they see the two as based on the same principle.”

The parallels between King’s efforts and Africans’ quest for independence were perhaps strongest in apartheid-era South Africa, where racist laws oppressed the majority Black community for decades.

In December 1965 King delivered a speech in New York denouncing South Africa’s White rulers as “spectacular savages and brutes” and called on the U.S. and Europe to boycott the nation, a strategy the West eventually embraced and that helped end White rule.

King was unable to visit South Africa after being denied a visa. But years later a bust of King was slipped secretly _ by diplomatic pouch _ into a South Africa still in the grip of apartheid.

American sculptor Zenos Frudakis said the U.S. government approached him about creating a bust of King that would be installed in South Africa for “political impact.” As it was barred by South Africa’s government from being displayed in a public space, the sculpture was dedicated in 1989 at the U.S. Embassy, visible to people outside the embassy fence.

People who were part of the struggle against apartheid spoke at the sculpture’s dedication, and Frudakis said he was impressed “as they were risking their lives to bring equality and freedom to everyone in South Africa.”

Today, the bust of King remains on display in a vastly different South Africa, which was transformed after anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela was freed from prison in 1990 and elected the country’s first Black president four years later.

Mandela was keenly aware of King’s contribution to equal rights and mentioned him when accepting the Nobel Peace Prize along with South Africa’s last apartheid-era president, F.W. de Klerk, in 1993.

“Let the strivings of us all prove Martin Luther King Jr. to have been correct when he said that humanity can no longer be tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war,” Mandela said. The Nelson Mandela Foundation plans to mark the anniversary of King’s assassination.

King’s inspirational speeches on love and justice, as well as his insistence on non-violent resistance, continue to resonate among some intellectuals and political activists in Africa, where many countries are now ruled by strongmen or democracy is in decline.

The civil rights leader was frequently cited by Ugandan activists last year as lawmakers moved to pass a bill that could keep the longtime president in power for many years more.

“We as a nation must recognize what Martin Luther King Jr. referred to as the `the fierce urgency of now,”’ one opposition activist, Mugisha Muntu, said at the time. “We too must make our voices heard.”