While segregation was still casting its ugly shadow over the U.S., the Homer G. Phillips Hospital was providing top-notch medical care to a predominantly African American part of St. Louis and training some of the world’s best Black doctors and nurses.

The 660-bed hospital closed 43 years ago, but the facility named for the man who led the fight to open a first-rate hospital for Black residents in segregated St. Louis is still revered by the city’s Black community. So a white developer’s decision to call a new three-bed facility the Homer G. Phillips Memorial Hospital has been met by a strong backlash that includes a lawsuit, protests and newspaper editorials decrying what some see as cultural appropriation.

“That smacks of racism to me,” said Zenobia Thompson, 78, who trained at Homer G. Phillips Hospital in the 1960s before eventually becoming its head nurse. “We are laser-focused and determined that that name will come down.”

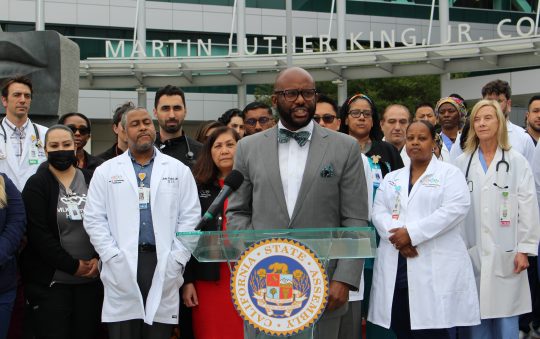

Darryl Piggee, a Black attorney who serves on the board of directors for the new hospital that is expected to open next spring, said it was his idea to name it after Phillips — to honor his legacy, not profit from it.

Related Stories

Brittney Griner Sentenced to Nine Years in Prison in Russia

“Hollywood Swinging:” MLB’s Top Sluggers Dazzle at Dodgers Stadium

“I’m from here, OK? So the idea that it was an appropriation isn’t true,” Piggee said. “I think the board is satisfied we are spreading word of the name of someone people should know about.”

The new hospital, which is in a different section of north St. Louis than the old hospital site, is part of developer Paul McKee’s NorthSide Regeneration project. Funded in part with nearly $400 million in tax increment financing, NorthSide seeks to transform a blighted area north of downtown with new housing, commercial projects and job-creating industry.

The hospital is a small but necessary part of the development. Medical care is scarce in north St. Louis, where about three-quarters of residents are Black and the median household income is 40% below the poverty line.

St. Louis’ prominent Black newspaper, the St. Louis American, noted in an editorial that it wasn’t opposed to the new medical center “but rather the insensitivity shown by the developer toward a community’s concern for his appropriation of the name of one of the Black community’s most hallowed and esteemed institutions.”

In July, Thompson and other nurses who worked at the original Homer G. Phillips Hospital filed suit, claiming trademark infringement. The suit seeks unspecified financial damages and a new name for the center.

Homer G. Phillips was a prominent Black attorney who a century ago led the fight for a new St. Louis hospital for Black residents in what was at the time one of America’s most segregated cities.

Passage of a bond issue provided the funding and the new hospital opened in 1937. Phillips didn’t live to see the hospital that would bear his name — he was shot to death in 1931 in an attack that remains unsolved.

Dr. Will Ross, a physician who is associate dean for diversity at Washington University School of Medicine and co-author of a book on the legacy of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, said it was the “social, health and economic anchor” of its neighborhood.

Walle Amusa, a longtime Black activist, recalled how the neighborhood around the hospital thrived. Scores of businesses served the nurses, doctors, staff and visitors. Well-manicured brick homes surrounded the hospital.

“It was like a family affair inside that hospital, and it was like a family community outside,” recalled Jobyna Foster, 86, a nurse for many years at the hospital.

Thompson agreed. She grew up in the neighborhood and recalled seeing the nurses walking proudly in their white uniforms.

“That’s when I decided to be a nurse,” she said.

Segregation created the need for the hospital, and many in the Black community say racism spelled its demise.

The two city-run hospitals became desegregated in the 1950s. For the next two decades, Homer G. Phillips remained open and continued to thrive, said Yvonne Jones, 75, who was a nurse there at the time.

Still, by the late 1970s, city leaders decided there was no longer a need for two city-run hospitals and ordered the closure of Homer G. Phillips, allowing the one in the white area of St. Louis to remain open. Amusa was among hundreds of people who formed a human blockade to stop the removal of patients and equipment from Homer G. Phillips, but it didn’t work and the hospital closed in 1979, six years before the other city-run hospital shut down.

Today, the massive brown-brick building that housed Homer G. Phillips still stands tall, serving as housing for senior citizens. The area around it has hit hard times. There are few businesses nearby, and many homes are vacant and condemned, with smashed-out windows and caved-in roofs. Crime is common and poverty pervades.

“When the hospital was closed it was like the death knell of the community,” Amusa said.

Piggee said the new medical center, and the NorthSide Regeneration project overall, will help revitalize north St. Louis.

NorthSide Regeneration has had its stops and starts since launching a decade-and-a-half ago. Some north St. Louis residents have complained that the hundreds of parcels of land purchased by the developer are nuisances, with few signs of progress. McKee did not respond to messages seeking comment.

But a new gas station and a grocery store have opened as part of the project. The most notable success was the federal government’s decision to build a $1.75 billion campus for the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency on nearly 100 acres (40 hectares) within NorthSide Regeneration’s boundaries, creating thousands of high-paying jobs. It’s expected to open in 2025.

The new facility sits a couple blocks from the NGA site. Hospital President Fred Mills sees it as a vital part of McKee’s plan for the area.

Mills, who spent decades leading larger hospitals, said Homer G. Phillips Memorial will offer 24-hour emergency room care capable of treating up to 15 patients at a time. The 15,500-square-foot facility includes an MRI imaging machine and amenities such as ports offering easy access to emergency dialysis and a room designed to make sure those with behavioral disorders are kept safe.

The developers have said the plans eventually call for expansion that could include a medical school, housing, a hotel and office space.

“Our dream and the goal is to have a larger facility, but you have to start somewhere,” Mills said.

Jones, who is president of the Homer G. Phillips Nurses’ Alumni, agreed that the new facility is badly needed. She just wants it called something else.

“We want to protect the name and legacy of Homer G. Phillips by having the current name removed from that building,” Jones said. “That’s all we want.”

Piggee said there are no plans to change the name.

“I understand their point of view but we just disagree,” he said. “I would hope we would be able to move on.”