This is in joyful and grateful homage to our illustrious foremother, Harriet Tubman, in this month of her transition and ascension, March 10, 1913. We offer sacred words and water to this leader and liberator, this all-seasons soldier, abolitionist, freedom fighter, strategist, teacher, nurse, advocate of human, civil and women’s rights, and this family woman: daughter of her parents and people, sister, wife, mother and aunt. At the heart, center and core of the life, work and struggle of Harriet Tubman is her focus on freedom. It is from the outset an inclusive and indivisible freedom: the collective practice of self-determination in and for community. Thus, it is not enough for her to free herself, for that to her was only an escape from the immediate bondage of the devilish enslaver and the radically evil system they built and maintained. And it was not enough to have crossed a line that in most minds meant leaving the land of bondage and entering the land of “freedom” and forgetting those left behind.

Indeed, for her, freedom meant more than seeking and finding a comfortable place in oppression and letting those who would and could follow you. That is why, having escaped form enslavement, she could only feel free and happy for a brief while and was thus compelled to turn around and bring all she could out of bondage so that they could enjoy the collective and inclusive freedom both she and they needed. For she tells us that all the people she loved and knew and who suffered and longed for freedom were back in the belly of the beast, fighting daily against the deadening, debilitating and acidicly corrosive and erosive effects of the Holocaust of enslavement, and she was determined and duty-bound to liberate them.

Harriet Tubman had imagined and prepared for freedom before she took that radical, irreversible and life-risking initiative to free herself, regardless of the costs and consequences. She had not simply hoped and prayed, but also hoped and practiced a freedom in the small and narrow space she carved out of the hard rock of the reality of enslavement which surrounded her. She began to think free, to study means to free herself and trained with her father and mother. She learned the lay of the land, the map of the night sky, the resources and pathways to freedom in the fields, forests, marshes and swamps. She memorized places of rest and renewal, of concealment and quiet, safehouses, allies and alternative routes and areas to avoid.

And she studied and learned the ways and wisdom of her own people who also brought knowledge of various and useful kinds about the fields, forests, waterways, plantations, pathways, enslaver patrols and persons helpful and harmful. And she counted on them to be courageous, strong and knowledgeable, and the historical records reveal she constantly cared for them and their children on the way, as well as for the weak, the ill and the aged, encouraging all and calling on all, even the fearful, to have faith, stay strong, act against their fears, apprehensions, doubts and “keep going” forward to freedom.

She gave her life in love to her people. Given such love for her people and the meticulous, dangerous and demanding time she spent again and again reaching out for them, teaching them to believe in themselves and their capacity and right to be free, we know whether the words people tell us she said or acts she’s supposed to have committed, are true or not true. For example, she never said, “I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves.” This is something that comes from the pathological conception of Black people and easy to accept if you already have a tendency to let the oppressor be our teacher and tell us how to understand ourselves in the most self-doubting, self-denying, self-condemning and self-mutilating ways.

The problem of liberating more enslaved Africans was not their lack of will, but her lack of more resources to achieve it, more allies to support it, and the numerous obstacles posed by the savage system and its supporters to save itself. The key lessons here of the awesome audacity, knowledge, skill, sacrifice, dedication, discipline and achievement of Harriet Tubman are lost, if we are deceptively diverted to indict our people instead of the oppressor. The problem of freeing more enslaved Africans couldn’t possibly have been that they didn’t know they were enslaved. For even the most chain-hugging persons among them knew they were enslaved, even if they lacked the will to be free.

Again, Harriet Tubman loved her people, knew the depth of their suffering through the lived experience of her own life and all the other horrific evidence of the moral and social savagery of White supremacy, masquerading as God-given, manifest destiny and other holocaust-justifying lies and ways of life. And she was determined to free them regardless of the odds, obstacles, the cost, consequences and the sacrifice required. Thus, she says, “I have heard (my people’s) groans and sighs and seen their tears, and I would give every drop of blood in my veins to free them.” This is the meaning of her declaration of commitment and defiance: “We must go free or die and freedom is not bought with dust,” i.e., purchased cheaply. Therefore, her battle cry “Go free or die” is directed not against the fearful ones wanting to go back, which again is taught to indict the people and divert from the awesome work she did, but to politically educate the people to the choice and practice of freedom. Likewise, her carrying a pistol, sword and rifle was not directed against the oppressed, but to protect them on the journey from the enemy oppressor. This is clear in her determination to have liberty, i.e., freedom or death and that no one would take her alive to torture, maim and kill her as they promised if they caught her.

Note how she says, “I had reasoned in my mind there were one or two things I had the right to: liberty or death. If I couldn’t have one, I would have the other” (emphasis mine). Thus, she had thought this out, not against her people, but for herself and her people. And reaffirming this, she said she would fight for freedom “as long as (her) strength lasts.” And she “prayed to God to make (her) strong and able to fight. . .” to the end. And she did. And when the Civil War was won, she continued to fight for the poor, aged and ill, for the veterans, for African rights, women’s rights and human rights, leaving a legacy of lessons and good.

And in this legacy no lesson is more important than the model and mirror and the enduring advice she gave in many ways about committing ourselves to righteous and relentless struggle for the shared good of a real and inclusive freedom. It is both a freedom from unjust and evil practices of domination, deprivation and degradation, and also freedom as the conditions and capacity to live good and meaningful lives and come into the fullness of ourselves. Again, however, she wants us to refuse to be deterred, diverted, dispirited or defeated and to wage the righteous and relentless struggle for a real and expansive freedom—not a fantasy freedom, a consumerist freedom, a machine-addicted and human-alienated freedom, but a freedom made real and enriched in and for community.

Regardless of the social savagery and madness that surrounds us, we must hold on and keep going. Regardless of the hurricanes and vicissitudes of history, we must hold on and keep going. And regardless of battle fatigue, sagging courage, sacrifices required and temporary blurred vision concerning our ultimate goal, we must hold on and keep going. Indeed, in her own words, she advises us: “If you’re tired, keep going; if you’re scared, keep going; if you’re hungry, keep going; and if you want to taste (real) freedom, keep going.”

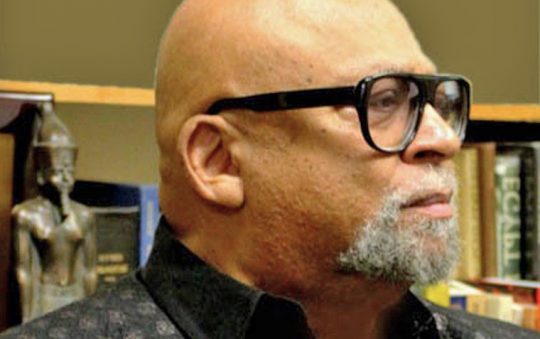

Dr.MaulanaKarenga,ProfessorandChairofAfricanaStudies,CaliforniaStateUniversity-Long Beach; Executive Director, AfricanAmerican CulturalCenter(Us);CreatorofKwanzaa;and authorofKwanzaa: ACelebrationofFamily,CommunityandCultureandIntroduction to BlackStudies,4thEdition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.