As we come to the end of the year and face the worst of winter that is yet to come, these words written earlier in honor of our poet laureate, Gwen Brooks, and the spirit of struggle of our people which she raises up and reminds us of, are on point, appropriate and uplifting. For they speak to how we as a people know our best and most beautiful selves, especially under stress and in struggle: “turning the river,” remaining “alive in ice and fire” and “conducting our blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”

The month of June has already folded into July and yet I still feel compelled to pay special hommage in this space to Gwendolyn Brooks-Blakely (1917 June 7—2000 December 3), although there is no way we can sum up the meaning and message of this poet, mother, mentor, woman and way-opener, this clear seer and sense-maker of things past, deep reader and revered teacher of things present, and prophet and pre-seer of our awesome ability to remain in love and “Alive in Ice and Fire” and indeed, bloom in the whirlwind of our oppression and our struggle against it. But we can harvest and replant some of the seeds she has sown, and become and embody the free and flourishing women and men that she called on to self-consciously dare “conduct your blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind”.

Gwendolyn Brooks did an extraordinary thing in her 50’s; she comes into Black consciousness in the spring of ‘67, mentors and learns from her young mentors whom she calls the “New Risers”, cites and quotes their works, breaks with her large White publisher and publishes with Broadside Press, a small Black publishing house which creates space and support for numerous emerging writers. An internationally recognized and respected Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize recipient, she joins the Black Revolt and aims “to write poems that will somehow successfully call all Black people:” everyone from schools to alleys and pulpits to prisons. Aware she must not imitate or cater to youth even in revolution, she says, “My newish voice will not be an imitation of the contemporary young Black voice, which I so admire, but an extending adaptation to today’s Gwendolyn Brooks”. And with this self-understanding, as Haki Madhubuti, one she called “tall-walker” and a favorite son and for whom she wrote and dedicated poems, says, she emerges as an extraordinary “example for us all, a consistent monument in the real”.

The point of departure for her new poetry is her conception of and commitment to Blackness. She accepts and embraces my assertion that “the fact that we are Black is our ultimate reality”. It is her introducing quote for her poem “The Sermon on the Warpland”, appears again in her “Primer for Blacks” and was her sole message at the Broadside Press 25th Anniversary Conference in Detroit in 1975. Indeed, she says in “Primer for Blacks”, “The huge, the pungent object of our prime out-ride/is to Comprehend,/to salute and to love the fact that we are Black,/which is our “Ultimate Reality”/which is the long ground/from which our meaningful metamorphosis/from which our prosperous staccato/group or individual can rise.”

Furthermore, our love of Blackness must be expressed in our love of each other—deeply, freely, and without fear or falseness, and in the struggle to clear free space for this sacred and mutual giving. In her poem, “An Aspect of Love, Alive in Ice and Fire: La Bohem Brown”, she speaks of a love in the midst of struggle which binds and makes each other more beautiful. She opens the poem saying, “It is the morning of our love./In a package of minutes, there is this We. How beautiful”. Distinct, yet united in love and struggle, the lovers understand themselves as “merry foreigners in our morning,/we laugh. We touch each other/are responsible props and posts./A physical light is in the room/Because the world is at the window/we cannot wonder long.” For there is work to do. The sister-woman describes the brother-man and co-warrior in love and admiration, prefiguring a current longing by Black women. “You rise./genial, you are in yourself again. I observe/ your direct and respectable stride./You are direct and self-accepting as a lion in African velvet. You are level,/lean,/remote./” The love is monumental and mutual, rooted in shared struggle and forever friendship. Thus, she says “There is a moment in Camaraderie/when interruption is not to be understood./I cannot bear an interruption./This is the shining day;/the time of not-to-end.”

She is conscious of the warped and warping character of an oppressive society which she calls “warpland”. She teaches resistance and raising up the confused and “self-shriveled”. She tells us, “Say to them,/say to the down-keepers, the sunslappers/the self-soilers, the harmony-hushers,/ Even if you are not ready for day/it cannot always be night”. Then, dare to hurry the dawn and give fullness to the day.

Again, in her First and Second Sermons on Warpland, she calls for us to criticize and condemn the tide of terrible things that overflow and flood our lives, but then to dare to change them. Thus, she says, “My people, Black and Black, revile the River./Say that the River turns and turn the River”. And we must recognize “the coming hell and health together” and “prepare to meet/(sisters, brothers) the brash and terrible weather;/the pains;/the bruising; the collapse of bestial, idols.

But regardless of the encircling chaos and evil, we must choose life and flourish. She says: “This is the urgency! Live!/and have your blooming in the noise of the whirlwind”, the source and site of our self-formation as persons and people and the fire and furnace of our testing and tempering. So, she asks us to “straddle the whirlwind”, defy death and “live and go out./Define and medicate the whirlwind”. It is in this struggle to live and flower, to understand and appreciate the dignity and divinity of each of us that we realize that “A garbage man is dignified/as any diplomat”. And that “Big Betsie’s feet hurt like nobody’s business,/but she stands-bigly-/in the wild weed”. And there “she is citizen/and is a moment of highest quality; admirable.”

In our striving to ground ourselves, grow and flourish, we must find ourselves in service and support of the poor, oppressed and less powerful, defiantly marching “in rough ranks. In seas. In windsweep…Black and loud. And not detainable. And not discreet”. And given the terrible toll the whirlwind of oppression takes on us, many of us might feel loneliness and even despair, but we must raise ourselves repeatedly and dare continue the struggle. Our foremother and mentor, Gwendolyn Brooks-Blakely says, “It is lonesome. Yes. For we are the last of the loud”, the last who dare shout freedom, scream justice and struggle loudly and relentlessly to open wide the windows and ways to a new world for us all. Indeed, we are the last who must and do strive to redirect the river, bloom in righteous Blackness and rising sun, and seize the historical moment and become the noise, whip and whirlwind itself in the interest of a world unwarped and constantly unfolding for the Good.

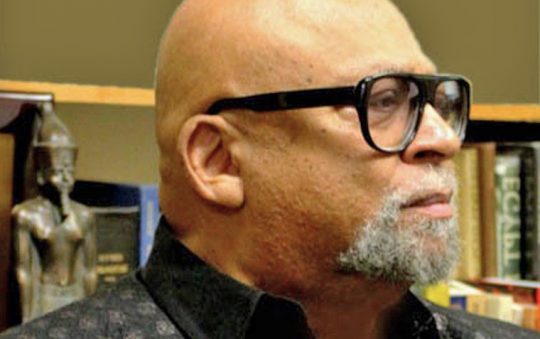

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.

12-26-16