When Melvin Gaines, Sr. contracted dementia and lost his memory, he also eventually lost his home as a result.

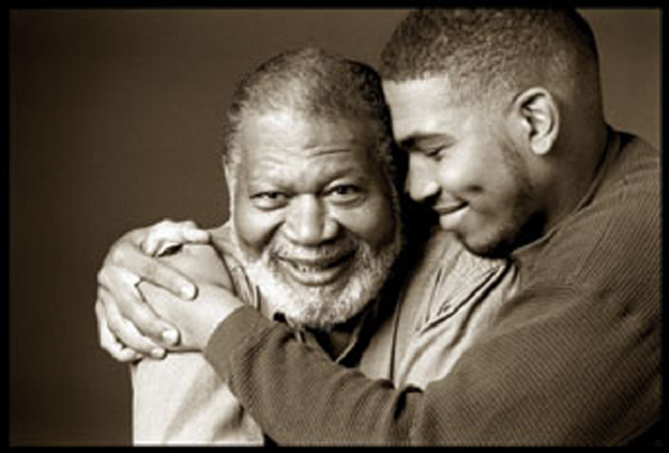

Bryan Gaines, his well-employed college-educated son, became his caregiver. His father’s resources were already scarce, barely enough to help care for him, he said.

Bryan’s 78-year-old father went from being a property and business owner to poor and homeless, according to Gaines.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness indicates that 564,708 people in the United States were homeless, as of 2016. Its “State of Homelessness in America” report further indicates that 50 percent of the homeless population is over the age of 50.

Health and safety risks, such as cognitive impairment, vision or hearing loss, major depression, and chronic conditions like diabetes and arthritis, are factors experts say.

Gaines had already been working on issues surrounding dementia, but focused heavily on Alzheimer’s given his father’s condition. Gaines initially felt there was no way he could handle the responsibility. Their relationship was estranged, according to Gaines, who said he was reared by his grandmother.

For as long as he could, Gaines provided 24-hour care for his father, but the expenses and tasks became too much to bear alone, he said. For instance, prescriptions cost approximately $900 for 30 pills, according to Gaines.

And after losing his house, Gaines’ father had to move into a facility, which required a $5,000 down payment, and money for other necessities, he said.

Eventually, Gaines opened up “The Melvin Gaines Center” (aka “Melvin Memory Care”), a care facility especially for his father, in South L.A.

“Because of poverty, he could not afford to be in a place,” Gaines stated. “I had the man in a place for one year … it costs $5,000 a month for him to live there, and it pretty much drained his account, but he got the worst quality of care that you could ever possibly want for $5,000 a month,” Gaines continued.

Gaines felt the only way he was going to provide his father with the type of care he needed with the amount of money he had was by opening the Melvin Gaines Center. He did so within one year, and made the full Alzheimer’s – Dementia care facility available to others to help offset the costs, Gaines said.

“We did well for a long time, but it was never very lucrative. It was just enough to take care of the people and get resources to the community,” Gaines recalled.

Unfortunately, his long-term plan for his father fell through, and Gaines had to close the facility after nine years.

“A lot of little things went on. It was just that the timing was bad. The housing market crashed. People were afraid, and so the business just didn’t ever take off to where I could get another facility up and running,” Gaines said.

Gaines said like a lot of care facility businesses in the Black community, insurance and the adequate type of care is very expensive, and ultimately, he just couldn’t afford it.

“It was a solution for my dad in the time of need, because he would have ended up in a low-level care nursing home, with pretty much very minimal care, and a quality of life that would’ve been very sad, like most people who can’t afford it … they just decline very quickly,” Gaines said.

Limited housing options are but one of the major impacts affecting seniors with dementia according to experts.

For instance, many large, assisted-living facilities and homes with trained 24/7 care staff exist, but they are not available to those with income levels between $500-1,500 per month, according to Marie Vernon, program director for All Hours Adult Care. The company helps transition seniors and adults looking for permanent long-term housing or care facilities, among other things.

Vernon said the typical rate for assisted living is $3,000, plus something called a level of care option. “That could put a person’s eating, diapering, and bathing assistance, and wheelchair or walking assistance in the level of $5,000 that they don’t have,” she said.

To get around these issues, she recommends that the state and federal government allocate more funds for homeless projects and senior care, as opposed to cutting state aid or Medicaid and Medi-Cal, particularly in California.

“Instead, they are trimming the budget under the belts of the poor, working class, and middle class, who now need long-term care in a facility or even at home,” Vernon added.

She said some solutions include recuperative care programs for people who need help with true, skilled, short-term nursing needs.

Meanwhile, Gaines continues working to improve quality of life for seniors with dementia. One of his latest creations is a hand-held church fan that outlines how to plan for Alzheimer’s when it hits home, he shared.

“Basically, it’s every single thing that people need to think about, once they find out that the person in their family or a friend has this disease. It takes them through the whole process, all the way down to making the final arrangements; everything I did for my dad,” said Gaines.

(This article was written/produced with the support of a journalism fellowship from New America Media, the Gerontological Society of America and the Retirement Research Foundation.)