DAYTONA BEACH, Fla. (AP) They are old men now, something Billy Jackson never had the chance to be.

They walked to the podium in the chapel of R.J. Gainous Funeral Home on Saturday to honor Billy and speak of the horrors they endured at the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, the bond they share with Billy.

The remains of more than 80 boys have been uncovered at Dozier. Billy died there in 1952 at the age of 13. His remains were sent to his sister Mattie Jackson in Daytona Beach last week. He was honored and buried Saturday.

Pastor Johnny Lee Gaddy came to Billy’s funeral from his church in Bushnell. He was sent to the Dozier school in 1957 for the same reason Billy was sent there _ skipping class.

Gaddy recalled being held down to a cot in the school building known as The White House as a massive-looking guard repeatedly beat him across the back with a worn leather strap.

The suction from the belt tore the skin off my body,” Gaddy said to the stunned group of about three dozen family members, friends and fellow survivors who attended Billy’s memorial service.

The state run, juvenile detention institution _ which opened in 1900 and wasn’t shuttered until 2011 _ is now synonymous with being one of the most horrific institutions in the country, where children suffered daily abuse meted out by a handful of administrators. The punishments were harsher against blacks and youngsters who tried to run away, and survivors also told of unmarked graves on the school’s property where those who had died “mysteriously” had been dumped into wooden boxes and buried.

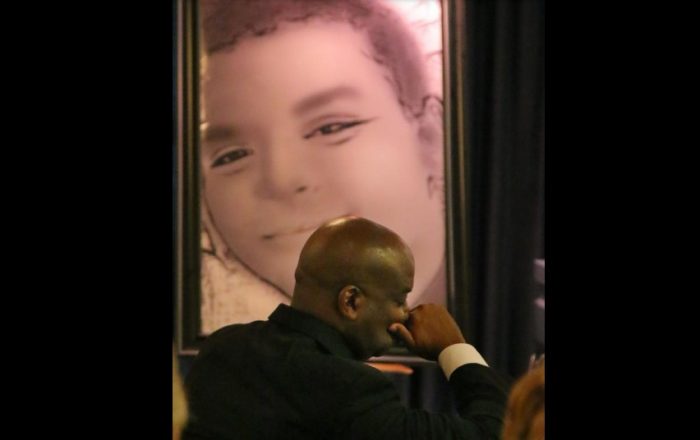

Jerry Cooper came from Cape Coral. Now president of an organization of Dozier survivors called the White House Boys, Cooper got sent to the reform school in 1961 for running away from home. He said he was beaten at least 135 times over the course of one night’s punishment and choked up as he explained how he saw others treated at the institution.

“Four other boys were hooked to the plow share. Even though we had mules,” he said.

Cooper said Dozier boys called kids like Billy rabbits, nodding toward the blue casket by his side. “He was a runner.”

On the third escape attempt _ and consequent beating _ Cooper said Billy was sent to the hospital, but didn’t last long after he was released.

Billy’s official death record states he died of pyelonephritis, a urinary tract infection that affects one or both kidneys, according to niece Ida Cummings of Washington, D.C. But the family feels strongly that severe beatings at the institution killed Billy. And several White House Boys agreed.

Johnny Walthour of Jacksonville, told the Florida Times-Union that he helped bury Billy’s body in October 1952. Walthour, who died earlier this year, recalled that Billy’s stomach was bloated and bruised.

“Mother told me they had beaten him to death,” Mattie Jackson said last week. Their mother, Susie Jackson, died just a few months after her son and Mattie believes her mother died from grief.

Skipping school and running away from home was a common way for boys to get sent to the reform school _ a fact not lost on those who attended Billy’s funeral and burial.

“It could have been me. It could have been anybody,” said Billy’s childhood friend, Roy Fletcher.

It could have been Daytona Beach Mayor Derrick Henry.

“There was a time or two that I cut class,” said Henry, echoing Fletcher’s words and the murmurs of many in the congregation. “The only right that we can make of this is to atone for this,” Henry said.

“This should not have happened. They suffered in a place that was assigned to help them. They took lives. They took dreams. They took hopes. Our goal should be that this does not happen to future generations,” said the mayor.

When Gaddy was taken from his home, he said he thought he’d have to go before a judge after getting into trouble _ just like Billy _ for skipping school. Gaddy said he stuttered as a child and hated the teasing. But he said the truancy officer cleared that up for him soon enough.

“He said, `N(asterisk)(asterisk)(asterisk)(asterisk)(asterisk), ain’t gonna be no judge. You goin’ to Dozier.”

Gaddy said it was easy to miss from the outside how terrifying the institution was for children who were sent there.

At first, he said, as a nature lover, he felt lucky.

“I thought to myself, `This is the most beautiful place. I’m glad to be here.’ But two weeks later,” Gaddy said, “my nightmares began.”

In his early days at Dozier, Gaddy recalled, a huge guard forced him onto the bed in The White House and told him to grab the sides of the cot for his predawn punishment. He said he looked like he was about 500 pounds.

As the strap connected with his bare flesh, Gaddy remembered his childhood reaction, “I’m just saying, `God, what had I done so bad?’ “

Gaddy said he didn’t speak up about his past for a long time.

“It was so hard. I lived through this, but I didn’t want anybody to know,” he explained, saying the other White House Boys were a catalyst to tell his story. He said he eventually came to peace with the awful memories.

“You can tear my body up _ but not my soul,” he said.

And while Billy may be at home and at peace, Cooper says there are still many who have a voyage yet to travel.

Walking away from the sandy grave site, Cooper talked about a task force the White House Boys are involved in and says while the investigation continues into the Dozier school, The University of South Florida is housing several unclaimed children’s bodies. Cooper said he is on a mission to not allow those remains to be reburied on Dozier school grounds.

“I’m fighting this hard” Cooper said. He doesn’t want the other children to remain in a place he calls “The 1,400 acres of Hell.”

“We were all in the same boat. And I love them all.” Cooper said.

Billy Jackson, surrounded by respect and love, was laid to rest in a blue casket at Mount Ararat Cemetery off Bellevue Avenue under a blistering afternoon sky in his hometown _ where his sister Mattie says he wanted to be all along.