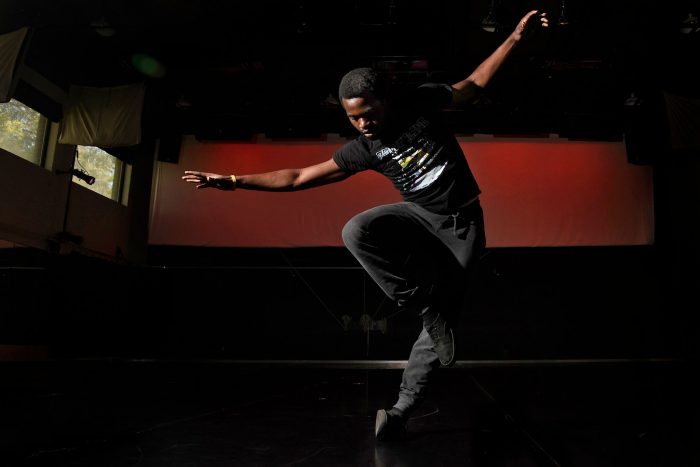

Tsiambwom Akuchu’s path to the stage at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., started with a little research.

Akuchu, who started break-dancing when he was a teenager, says “hip-hop’s history is embedded in its movement.” You can’t separate that history from the moves themselves.

He began exploring the ways that dance and movement are tied to Black history in the United States while working on his Master of Fine Arts degree in acting at the University of Montana. He took an African-American history course to further his understanding.

It developed into a personal, solo dance piece that he choreographed and performs himself. The 11-minute piece tracks “the history of black bodies in this country” through black dance and music, reaching back to African roots through plantation ballads to the Harlem Renaissance, and ends with Kendrick Lamar.

Earlier this month, he performed “EveryMan (Alright)” at the Kennedy during the American College Dance Association’s national festival. He was one of only 30 selected for the concert, a “once-in-a-lifetime experience,” he said.

“I’m still just reeling at that,” he said.

(asterisk)(asterisk)

In March, Akuchu took the piece to Boulder, Colorado, for the annual Northwest regional conference of the ACDA.

There, the professional adjudicators described his work as “an evocative and stirring piece, representative of the African-American experience from slavery to the present. The work is deeply embodied, solid in its canonical foundation, eminently relevant and critically necessary; an injection of survival.”

He received a standing ovation, the only one at the conference, and was selected for the Washington trip.

Akuchu’s research, choreography, acting and dancing abilities all came together to make a powerful piece, said Nicole Bradley-Browning, head of the UM Dance Program.

She said his ability to transport audiences through time and embody that history is a task that not many choreographer-dancers would be able to pull off. The fact that it’s a lengthy solo performance adds another layer of difficulty.

“Holding the stage by yourself for 11 minutes _ it’s a tall order and he pulled it off,” she said.

(asterisk)(asterisk)

Akuchu grew up in Cameroon in West Africa, and his family moved to Atlanta when he was 10. He started teaching himself to break-dance when he was 17 or 18, picking things up from other dancers or the occasional YouTube video.

While he was an undergraduate in acting at Georgia Southern University, he would alternate theatrical productions and shows with a dance crew that he’d joined.

It wasn’t until his senior year that his professors realized he could dance– a valuable additional skill for an actor –and encouraged him to apply those movement skills in his theater work.

He almost had a big break, one that didn’t pan out. He realized how much of success is luck, and decided to look at graduate school. “I want to be good. I don’t want to be lucky,” he said. “I want to know that I’m good at what I do.”

He was accepted to the University of Montana’s graduate program, where he began studying dance _ ballet, jazz, modern _ along with acting. Theater-goers may have seen him perform as Mercutio in UM Drama’s production of “Romeo and Juliet,” or in a key role in the spring production of “Everyman.”

(asterisk)(asterisk)

Akuchu has studied physical theater, such as ways to define a character or tell a story through movement alone, and so it’s difficult to separate his theater work from his dancing. The solo piece grew in part out of “Everyman,” his final theatrical piece before graduating, hence the title.

The piece opens with the sounds of chains, as Akuchu stands on a pedestal, or perhaps an auction block. He begins with an “abstracted” version of a dance from his tribe in Cameroon, known as the Babanki, or Kedjom. He pairs it with traditional movements from the ring shout, a celebratory ritual dance that slaves performed as “a mode of resistance” or a “space where they could reclaim their roots.” This section is set to a reconstructed ring shout, which has elements of call-and-response and repeated phrases, he said.

He found a recording of Ice-T reciting Harlem Renaissance poet Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” and set it to a plantation ballad called “Trouble So Hard” by Vera Hall.

He cycles forward in time to dances like the cakewalk, a “form created by slaves on plantations as a way to mock their masters,” he said.

“Interestingly enough, the cakewalk was then appropriated into minstrelsy, created by White people as a way to mock Black bodies,” he said. He contrasts it with contemporary dance styles, like house, which developed along with house music in the 1970s and ’80s.

“Most dance styles have a musical form,” he said. “When house music was coming up in like Chicago and New York, house dance was being developed at the same time. So the music would drive the dance which would drive the music.”

He juxtaposes contemporary break-dancing with capoeira, a “Brazilian dance style that slaves would use to disguise the fact that they were training to fight,” he said. He saw similarities not only between the movements, but their roots in resistance of one form or another.

Break dancing developed in the in the late 1960s and early 1970s, where it was an alternative to gang violence and poverty in a city that resembled a “bombed-out war field,” he said.

It culminates with Lamar’s anthem “Alright” and powerful, contemporary dance moves. There are even more elements than that in the piece.

“Every aspect of it is very deliberately chosen and constructed to have multiple, multiple meanings,” he said.

The performances have started to open doors for another phase of his career. At regionals, a dance professor at Brown University invited Akuchu to a festival, DANCE Now, in Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater in New York in September. He’s been approached about teaching and guest artist residencies, as well.

“Things are still settling,” he said, seeming in awe of the fact that these new career opportunities in the dance world are coming so fast.

“I just graduated with my MFA in acting,” he said.