BUSTAMANTE and MANLEY, the fathers of Jamaica’s independence

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the independence of Jamaica (August 6), and being the home of the world’s fastest man. (Usain Bolt).

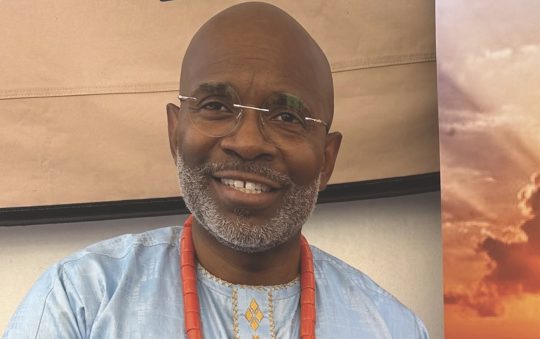

SIR ALEXANDER BUSTAMANTE – “The First Prime Minister of Jamaica, and one of the most influential political figures in the West Indies”

Born William Alexander Clarke in 1884, he became famous as Alexander Bustamante (a name he adopted in honor of an Iberian sea captain, who befriended him in his youth), a tireless labor leader with the ability to motivate his fellow countrymen; the first chief minister with an elected legislature but under limited self-government; and the first prime minister, and one of the architects of Jamaica’s independence from Great Britain. For much of his life, he lived under the tyranny of British colonialism with Jamaica existing as a crown colony.

Perhaps Jamaica’s most flamboyant and charismatic politician, Bustamante’s father, Robert Constantine Clarke, was the White overseer of a small, mixed-crop plantation called Blenheim, on the isolated northwestern coast of the island. (Because of the second marriage of his grandmother to Alexander Shearer, he became distantly related to Norman W. Manley, Michael Manley and Hugh Shearer – all of whom would eventually be chief minister and/or prime ministers of Jamaica). His mother, Mary Wilson, was a Black woman from the rural parish of Hanover.

Before leaving Jamaica in 1905, he attended primary school and did private studies. Overall he received little formal education in Jamaica and was disdainful of a plantation apprenticeship, which would have led him to succeed his father as an overseer. He migrated to Cuba where employment opportunities were expanding in the sugar industry; there he also served in the Spanish army. From Cuba, Bustamante went to Panama where he spent almost ten years; he met Mildred E. Blanck. While on one of his shorts trips back to Jamaica, they were married in Kingston. They then traveled to New York City, where he worked in a hospital before returning to Jamaica in 1932. In his travels, he noted the indignities, the exploitation and racial oppression of colonialism, so back in Jamaica, he campaigned for worker’s rights and never lost sight of the suffering and abject poverty of masses of his people.

Though a successful businessman, Bustamante’s concern for the plight of the workers – especially sugar can plantation workers – led him to organize the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union in 1938. He had also written a series of letters to “The Daily Gleaner,” Jamaica’s daily newspaper, and other British newspapers, highlighting the wretched social and economic conditions that the working masses were forced to endure. He realized that the system under which colonialism flourished would only be countered by mass mobilization of the working class and he sought to capitalized on the dissatisfaction of the under-privileged – those who were treated as second, third and fourth class citizens in their own country.

The British imprisoned Bustamante for allegedly violating the Defense of the Realm Act, but actually for his anti-colonial activities under the guise of being a troublemaker. The widespread discontent for the British that fomented under Bustamante’s leadership began to be noticed in other colonies. His activities were not confined only to Jamaica, but also in Trinidad, Barbados and other West Indian islands where the British Empire was loosing its grip. (About that time, the work of Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey was ever-present among Black people throughout the Caribbean and Africa).

When Bustamante was released from prison in 1942, he continued his anti-colonial activities and founded the Jamaica Labor Party (JLP) and served as the mayor of Kingston, the capital of Jamaica. His rival was his cousin, Norman Manley, who founded the People’s National Party (PNP). By that time, Jamaicans had been granted universal suffrage and during the first general election that followed, the JLP won 22 of 32 seats making Bustamante, the country’s chief minister and leader of the government, though still on a British leash.

During the second general election, the JLP won again, but in the third election in 1955, the PNP won making Manley the chief minister and Bustamante, the opposition. That same year, he was granted a knighthood by the Queen of England and officially became Sir Alexander Bustamante.

Though knighted by the Queen, Bustamante was still considered a troublemaker by the British who were experiencing anti-colonial turbulence in many of the West Indies islands in the wake of Jamaica’s agitation. They (the islands/colonies) eventually formed the West Indian Federation consisting of 10 islands/nations which Bustamante initially supported and then opposed. It lasted for approximately four years (1958 to 1962), but as British colonies, they were hindered by nationalistic attitudes and their individual need to be free from the British blinded them from realizing the strength in their unity. Also not yet being totally and fully independent, they each held limited legislative power. Bustamante’s tepid support led Jamaica’s withdrawal and a breakup of the federation.

Along with several other members of a Joint Parliamentary Committee, Bustamante helped draft the independence constitution which was followed by the signing of the independence agreement in London. In the April 1962 election, JLP was returned to power and on August 6, Jamaica gained its independence. Bustamante became the country’s first Prime Minister.

That same year, he married his second wife, Gladys Longbridge.

Two years later, Bustamante, because of failing health, withdrew from active participation in public life, turning over the day-to-day executive power to his deputy, Donald Sangster. He officially retired in 1967. Bustamante was honored as a ‘National Hero of Jamaica’ in 1969.

Sir Alexander Bustamante died on August 6, 1977, the 15th anniversary of Jamaica’s independence. He was 93 and was buried in the shrine for prime ministers.

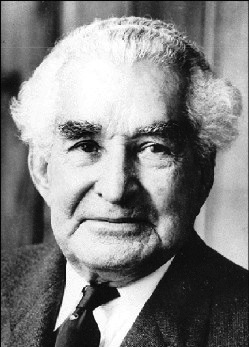

THE HONORABLE NORMAN MANLEY – “The second chief minister of Jamaica, advocate for universal suffrage and one of the architects of the independence agreement.”

“I say that the mission of my generation was to win self government for Jamaica; to win political power which is the final power for the Black masses of my country from which I spring.”

Those were the words of Norman W. Manley who was born on July 4, 1893, a time when the British ruled Jamaica as a part of its evil empire. Later on, when Jamaica gained its independence, Manley said that the mission was reconstructing the social and economic society, and the life of Jamaica. And this he did along with many other freedom fighters including his cousin Alexander Bustamante with whom he sometimes traveled different, but parallel paths that were aimed at the same goal – the independence of Jamaica.

Manley came from a mixed race family, and as a young man, he was a brilliant scholar and a daring athlete. He won a scholarship in 1914 to study law at Oxford University, England as a Rhodes scholar. (At that time, there were no independent universities in the British West Indies and as a British colony, Jamaica was subjected to British law. Jamaicans had to go to England to study law to become lawyers in their own land). Manley paused from his studies during World War I and enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery; he returned to his studies in 1919 and was admitted to the bar in 1921.

Returning to Jamaica as a barrister, the economic conditions drew Manley to public service where he gained prominence for his work on behalf of workers and labor troubles. He became a strong advocate for their causes and help form the first large cooperative, the Jamaica Banana Growers Association (JBGA). As its attorney and advocate, the JBGA challenged the United States-owned United Fruit and the British-owned Elders and Fyffes companies which produced a favorable contract for the workers and the United Fruit. Manley also realized that in order to restructure Jamaican society to be beneficial to the masses, direct political action was necessary.

In early 1940s, Manley founded the People’s National Party (PNP), ostensibly to secure universal suffrage for the people and to use those rights to build a political base. At the same time, his cousin, Alexander Bustamante, had founded the Jamaica Labor Party (JLP) with fundamentally, similar objectives. As political rivals, they were competing for much of the same constituency and their rivalry would have been healthy if they were competing in an independent, sovereign country. Though they held general election in 1944, they were still subjected to the British. However, it was a step in the right direction: their efforts resulted in a new constitution and placed the country an inch closer to independence.

(Universal suffrage is loosely defined as the right to vote; though it does not guarantee the opportunity to vote in those instances where the rules are handed down by a dominant power that granted suffrage grudgingly)

After the founding of the two main political parties and the first general election was held, the JLP was victorious. Manley became leader of the opposition party and continued to educate the Jamaican people about the reality of politics and the need for independence.

In addition to his political activities, Manley still practiced law as his main source of income and keep in touch with the Greek letter legal fraternities. As a member of the African American Alpha Phi Alpha, he delivered a speech entitled “To Unite in A Common Battle” in 1945 at the general convention in Chicago, Illinois.

Back in Jamaica, politics consumed much of his time. The PNP won the next election and Manley became the nation’s second Chief Minister in 1955; it was ten years since universal suffrage had been granted. He remained chief minister until 1962. During that time, he became a strong advocate for the West Indies Federation, which was established in 1958 to unify British colonies into a single unit to fight for their independence.

Inter-island bickering ensued and the federation lasted only four years. In addition, Bustamante’s opposition to the body diminished Jamaica’s participation in that body. However, Manley used has political influence and called for a referendum – unused in Jamaica at that time – to let the voters decide. And they decided against Jamaica’s continued participation in the federation and hastened its demise.

After Jamaica’s withdrawal from the federation, Manley began to focus on independence for his country. He chaired a joint committee set up specifically for that purpose and led it to London to negotiate independence for Jamaica. (Bustamante was a member of that committee).

Manley’s PNP lost the next election to JLP, so that when Jamaica gained its independence, Bustamante was in charge and thus became the country’s first prime minister. Thereafter, Manley again became the leader of the opposition party. He retired from politics in 1969 and was honored as a ‘National Hero of Jamaica’ along with Bustamante, Marcus Garvey and others.

Manley died in September 1969. Three years later, his son, Michael Norman Manley became Jamaica’s fourth prime minister.

[FOOTNOTE: Some of the words used in the Jamaican style of English, adopted from England, differ in spelling from the same words in American form of English. Their spellings have been changed in the above to facilitate American readership. For example: HONOR was HONOUR; LABOR – LABOUR; REALIZED – REALISED; ORGANIZED – ORGANISED; FAVORABLE – FAVOURABLE … and so on. The same applies to the date: in the Jamaican form of writing, OCTOBER 2nd 2009 would be “2-10-09,” whereas the American version would be “10-2-09.”]