Black physicians, nurses, and healthcare professionals held a dialogue on racism, discrimination, and how the two affect their healing efforts.

They are on the front lines treating victims of social injustice every day, however, they are also victims of inequality and discrimination, they expressed.

LACMAHeals and the National Medical Association hosted the roundtable discussion, “African American Physicians – The Searing Journey” roundtable discussion at the Los Angeles County Medical Association Headquarters downtown on Aug. 31.

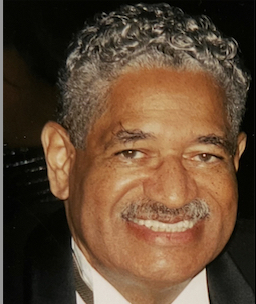

Dr. Brian Williams, renowned trauma surgeon, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas, was the featured guest.

He was thrust into the international spotlight when he spoke candidly to media about his position on the lack of open discussions on race and racism in America.

He spoke during a hospital press conference after treating the police officers who were shot during a protest against killings of Black men in Louisiana and Minnesota.

Williams has experienced clearly profound, professional changes since that night, and the status quo no longer became acceptable, he said.

“Personal changes. Spiritual changes … the Brian Williams that existed the day of July 7 going into work, he withered on the vine. There is a new person that’s emerging,” Williams shared.

He said he had been comfortable in his position with advanced degrees, a prestigious job, and well paid. He loves what he does, going to work every day, taking care of patients, and teaching students, he said.

“Still, that did not make up for the emptiness that I felt, knowing that I wasn’t being authentic about the impact these macro and micro aggressions that were occurring weekly. It was non-stop at my job,” Williams said.

He told himself his life was not that bad compared to his father and grandfather, and to focus on his blessings, not what he didn’t have.

“But in the end, when you can be so dehumanized based on the color of your skin, none of that matters, and since that night, I now acknowledge that. I’m not trying to hide that. I’ve pulled off that mask that had become a second skin for me, and I’m just stepping out into my truth,” Williams said.

The very private person who kept his emotions inside, who avoided talking about controversial issues, particularly about race, said he is very afraid. Still he is on a mission to help others that feel like him, and bridge the gap that transcends from diversity to understanding.

“Now that I’m out there, I can’t pull it back if I wanted to, but I don’t want to because that was a very unfulfilling existence for me,” Williams said.

Though petrified at the uncharacteristically public stand he had taken, he never had a moment of regret, he told the Sentinel.

Other guest speakers were Dr. Vito Imbasciani (president of LACMA), Dr. Richard Baker (LACMA African American Physician Advisory Committee Representative), Dr. Anne Staveren (President, Charles R. Drew Medical Society), and Gustavo Friederichsen (CEO of LACMA), who facilitated the dialogue.

The event helped kick off Imbasciani’s new presidency at LACMA. It also began LACMA’s year of engagement of doctors who work so hard they cannot fulfill other advocacy requirements.

“What we’re doing here tonight with one particular community is something that we intend to do with many, many other communities … We’re not here to lead tonight … We’re hear to listen,” Imbasciani stated.

Friederichsen launched a Q&A during which leading Black physicians shared their harrowing stories. They talked about the practice of medicine in terms of economic challenges, or whether barriers to success were regulatory or policy based.

Staveren noted Black doctors, particularly ‘baby boomers’ have gone through the status quo to get where they are, and there wasn’t a lot of flexibility to veer off that path if people wanted to become physicians.

“What are the footsteps or what kind of fire proof suits can we have for this searing journey,” she questioned. “Is it more of building a greater village for advocacy, a greater village so that we feel more comfortable for speaking out,” she continued.

Jordan Rivera, a fourth year student at Keck School of Medicine of USC, said he is one of five Black men in his class of 200. There is pressure to be exceptional, and if people notice at any moment two of them are hanging out, dynamics change, he said.

“It’s like you’re some type of crew, you’re some type of pack, but there’s no understanding that the rest of them have been hanging out the entire time,” he said.

He highlighted a few micro aggressions he said are debilitating at times. “I’ve had faculty members refer to Black patients as Negro patients. I’ve studied with friends using study guides that have been passed down through the years, going back to the traction alopecia. It’s written in that study guide as ‘ghetto braids,’” Rivera said.

His challenge has also been having to take the extra social obligation to try and correct in a manner that has been accommodating to the dominant society’s fragility of their sensitivity to race, he said.

“I think that’s some of the things that need to stop. Instead of us bearing the burden and feeling sensitive or trying to be accommodating to that sensitivity, I think it comes with actually letting people know that they’re making mistakes and that they’re hurting other people,” he said.

His program has been responsive and among other things, has increased the number of enrollment of Black males, he noted.