We come from a culture where drums talk; songs and singing lift us into the heavens and sustains us on earth; sculpture, painting and carving come alive; and dance is a creative link and life-line to the Divine.

And we come from an ancient and ongoing culture where the ancestors and elders, teaching the sacred narrative of creation, say that “In the beginning was the word and music.” And the word was first exceptional insight and image and became rhythmic speech, seeds of creation, vibrating with vital force, creating movement and music that constructed and colored the world.

Thus, creation became art and art became creation and by this vital emulative and creative practice humans can honor the ethical and aesthetic imperative to constantly repair, renew and remake the world, making it more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited, which is Kuumba, creativity, the Sixth Principle of the Nguzo Saba.

In this month dedicated to Black music, then, it is important for us to reflect not only on the special role music and the other arts play in our lives, but also the role the makers of music and other arts play in our culture and in our lives. For whatever else artists might think, imagine or assert, they are embodying and expressing certain views and values, certain conscious or unconscious commitments to the way people should live their lives and how they should think about and engage the world.

And given the importance of music and other arts in our lives, we must be clear about what we are creating, listening to, looking at and whether we are dancing to and participating in our own degradation or creatively, righteously and rhythmically reaffirming life, love, struggle and other good in the world.

In the Black and golden age of art and struggle we call the Sixties, our philosophy, Kawaida, played a central grounding and guiding role in the Black Arts Movement and a similarly significant role in the Black Liberation Movement. And since our organization Us and our philosophy Kawaida are still in this unfinished fight for freedom of our people, I would like to draw from and build on what many call a seminal article I wrote that became a fundamental reference and resource for how we should do and relate to Black art and how it should relate to us, our struggle and the world and the time in which we live.

The title of this article is “Black Art: Mute Matter Given Force and Function.” It was titled this way to suggest that the materials we work on and with are mute until we give it voice, value, force and function like the original Creator.

I begin the article by saying “Black art, like everything else in the Black community, must respond positively to the reality of revolution. It must become and remain a part of the revolutionary machinery that moves us to change quickly and creatively.”

Here I am arguing that the first critical role of the artist is to speak to the conditions and the times in which they live. As Nana Nina Simone informed us, “It’s the artist’s duty to reflect the times in which we live.” They must do this, we argued, conscious and respectful of the fact that we are a people in oppression and resistance and as Nana Paul Robeson and Nana Haji Malcolm state respectively, “the battlefront is everywhere” and “wherever Black people are is a battleline.” And artists have an obligation to speak to that and choose to do their work conscious of and concerned with this reality.

Moreover, this cannot be a superficial engagement with symbolic flying of flags and wearing of signs and symbols and pretending a depth of commitment that is not there. They must do art in such a way that it becomes part of the struggle of the people in substantive and sustained ways. As Nana Haji Sekou Toure taught us, “To take part in the African revolution it is not enough to write a revolutionary song. You must fashion the revolution with the people and if you fashion it with the people the songs will come by themselves and of themselves.”

Indeed, he goes on to say, “There is no place outside the fight for the artist or for the intellectual who is not himself concerned with and completely at one with the people and the great struggle of Africa and of suffering humanity.”

As I argued then and contend now, all Black art, regardless of any technical requirements, must have three basic characteristics which make it revolutionary. In brief, as Nana Leopold Senghor and tradition affirm, it must be functional, collective and committing.

To be functional, it must be useful to our people and the world, for we reject the false doctrine of art for art’s sake. For it to be useful, then, in this critical time of turning and tumult, it must, in the most creative and conscious of ways, praise and empower the people, expose and oppose the oppressor, and contribute definitively to the liberation struggle of our people. In a word, it must serve our people.

As Nana Elizabeth Catlett states, “I have always wanted my art to serve my people, to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.” Thus, she said, “We have to create an art for life and liberation.”

The second characteristic and requirement of Black art is that it must be collective. In a word, it must be from the people and be returned to the people in a form more beautiful and colorful than it was in real life. As Nana James Baldwin wrote of the Black artist that “to continue to grow, to remain in touch with himself and the community” from which he comes, he needs the support of that community.

For he concludes, “The responsibility of a writer is to excavate the experience of the people who produced him.” And then he must speak their special cultural truth to them and the world.

Here Nana Langston Hughes reminds us of a central “mission of an artist is to interpret beauty to people – the beauty within themselves.” And Nana August Wilson, grounded in Kawaida philosophy which insists on Black people and Black artists standing on self-defining and self-affirming ground, states that he stands on the sacred and self-defining ground of our ancestors, “men and women who can be described as warriors on the cultural battlefield,” especially during the Holocaust of enslavement.

And “As there is no idea that cannot be contained by Black life, these men and women found themselves to be sufficient and secure in their art and their instructions.” Thus, as I have written, “the Black artist can find no better subject than Black People themselves, and the Black artist who does not choose or develop this subject will find himself unproductive.”

Finally, Black art must be committed and committing. It must commit us to liberation, revolution and radical change. It must commit us to all that is us – our achievements of yesterday, our struggle of today, and our sunrise and flourishing of tomorrow. This is a commitment that includes the artist and community linked and locked in a mutually beneficial embrace of creation in sustaining of good, beauty and rightness in the world.

In conclusion, I wrote, “Let our art remind us of our distaste for the enemy, our love for each other, and our commitment to the revolutionary struggle that will be fought with the rhythmic reality of a permanent revolution.”

And in this uprooting and overturning of oppression and the upturning and creation of the good, new and possible, let us as Nana Gwendolyn Brooks taught us “nevertheless live” and dare and continue to “conduct (our) blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”.

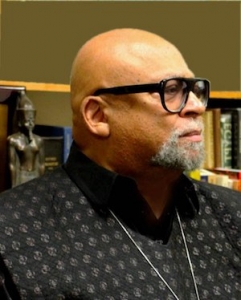

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.