Every holiday of every hero or heroine we celebrate is, at the same time and in equal measure and meaning, a celebration of our people, indeed a celebration of ourselves. Indeed, whether we believe they are chosen and raised up among us by heaven or history or both, they find their foundation and footing, their mission and meaning in the lived experience, the cultural values and practices and the historical and ongoing struggles of our people.

And so, it is with all those who took up the banner and moved to the frontline on the battlefield for freedom, and who served, soldiered and sacrificed in ways sorely needed and eminently notable.

These, of course, are too numerous to name, but they include Nanas Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, Maria Stewart, Mary McLeod Bethune, A. Philip Randolph, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Marcus and Amy Garvey, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Haji Malcolm, and so many others. And each and all of these are true daughters and sons, servants and soldiers of their people, our people, Black people, reflecting the greatness, sacredness and soulfulness of their people as well as of themselves.

Thus, whatever the lessons and legacy gleaned from the rightfully uplifted life and struggle of Nana Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., none is more important or essential than how this is meaningfully and continuously linked to understanding and honoring the people who produced him. And so, again, it is with all the others who through dedication, discipline, sacrifice and tireless struggle became noble witnesses of our sacred lives and righteous struggle to the world.

I speak here of our people, the African American People, a soul people, a sacred people, a resilient and resourceful people, righteously and relentlessly struggling to be ourselves and free ourselves, flourish and come into the fullness of ourselves. And it is the Black Freedom Struggle in this country, rooted in our culture of righteous resistance to evil, injustice and oppression and our ongoing struggle for the good in the world, that served as the fire and furnace in which he and all others were tested and tempered and came into their own.

In fact, Nana King would not have been grounded in his particular and essential moral and spiritual principles, harbored and held to hope and faith that sustained him in the most difficult and demanding times or achieved what he did without his people and the moral and political culture and support they provided for him to immerse himself in and draw from continuously. Clearly, he is not unaware or uncaring concerning his relationship with his people or the historic transformative role they had to play and did so, in expanding the realm of human freedom in this country and the world.

This is why on the eve of his assuming leadership of the Montgomery Improvement Association, from which he emerges as a national and international leader and freedom fighter, he gives them a central charge and challenge. Thus, he defines Black people as a moral and social vanguard whose righteous and radically transformative struggle would compel historians of future generations “to pause and say, ‘there lived a great people – a Black people – who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization’. This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility.”

Moreover, in an essay titled “A Testament of Hope,” which he wrote in 1968 prior to his assassination and martyrdom in April of that year, he affirmed his faith in his people’s, our people’s capacity and role as a moral and social vanguard. He stated that he believed we had “in (our) nature the spiritual and worldly fortitude to eventually win (our) struggle for justice and freedom.”

He said, “It is a moral fortitude that has been forged by centuries of oppression,” and we add, forged by righteous and relentless resistance in those centuries of savage oppression. Continuing, he states that “Black (people) in America can provide a new soul force for all Americans, a new expression of the American dream that need not be realized at the expense of other (people) around the world, but a dream of opportunity and life that can be shared with the rest of the world.”

Here Nana King borrows from and builds on the world-encompassing views of our moral concerns and sense of responsibility deeply rooted in the moral and political culture of his people. He, like his contemporary Nana Haji Malcolm, sees our moral stance and political responsibility as including a vision of and commitment to freedom and justice as a shared good in the world.

Also, Nana King finds common ground in this shared moral and political culture with Nana Anna Julia Cooper who precedes him and who affirms that in our culture “we take our stand on the solidarity of humanity, the oneness of life and the injustice and unnaturalness of all favoritism whether of gender, race, country or condition.”

And of course, this moral vision and accompanying ethical imperative is found also in the sacred teachings of Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune who taught us as a people and as a joint project with others that “We must remake the world. The task is nothing less than that.”

It is important here to stress again that Nana King and all other honored ancestors recognized and appreciated both the particular and universal character of our struggle, mission and message to the world. Indeed, as Kawaida reads it, our liberation initiatives are particular in our efforts to be ourselves and free ourselves and to speak our own special cultural truth and make our own unique contribution to the reconception and reconstruction of U.S. society.

But, it is universal in their clear and concrete contribution, as Nana Cooper, Bethune, Malcolm and King note, to expand the realm of human freedom and justice in the world so that all can equitably share in the good and goods of the world.

This is again why the essential moral and political message of Nana King and all our other honored ancestors are not simply about civil rights, but about human rights, rights of freedom, justice, equality, security of persons and people, and to the conditions and capacity for a good, full and meaningful life. Haji Malcolm clearly draws the necessary distinction between civil rights, granted by a government, and human rights which he called God-given natural rights, rights we have as human beings, regardless, as the Husia teaches, of time, place or biological and social characteristics or conditions.

Here it is important to stress again that in discussing Nana King, we not accept the dominant society’s renaming and redefining the Black Freedom Movement as the Civil Rights Movement. For it reduces the moral meaning and scope of Nana King’s and our peoples’ concerns and struggle. Also, it leaves out the Black Power phase of the Black Freedom Movement, producing such distortions as calling even Haji Malcolm a civil rights leader when in fact he criticized the classification of our struggle as a civil rights one and called on us to understand ourselves as waging a human rights struggle.

Moreover, such a renaming also unnames the Blackness of our struggle, giving without rightful resistance the dominant society definitional deference and power to the detriment of truth, history and our people. Indeed, as Kawaida teaches that one of the greatest powers of a society, institution or person is the power to define reality and make others accept it even when it’s to their disadvantage.

Dr. King recognized this deadly and deforming definitional power, speaks of the various sinister sites of it in the daily papers, history books daily life, and what he calls the “cultural homicide” directed against us of which it is a vital part. And he urges us to resist these assaults on our dignity, rights and life with a radical “divine dissatisfaction.”

Moreover, he praises our people for the “courageous and creative” ways they have struggled, maintained community and touched and turned the consciousness and conscience of the world. He says of our people in his Testament of Hope, “They have left the valley of despair, they have found strength in struggle, and whether they will live or die, they shall never crawl or retreat.” And with allies, they will in struggle “shake the prison walls until they fall.”

He notes in closing that “it’s a paradox that these (Blacks) who have given up on America are doing more to improve it than are its professional patriots.” Here again, he places hope in those whose divine dissatisfaction with injustice, unfreedom and oppression, “the poor and despised,” those strengthened in struggle and blamed for “arrogance, lawlessness and ingratitude” will achieve “the radical reconstruction” America needs.

In a word, honoring our ancient ongoing and living moral and political tradition of our people, we, in alliance and struggle “will fight for human justice, brotherhood (and) secure peace and abundance for all” and inevitably achieve these vital goods. Indeed, he assures us in his final speech that “We as a people will get to the Promised Land!”, that is to say, achieve the essential ground for a shared and inclusive African and human good and the sustained well-being of the world and all in it.

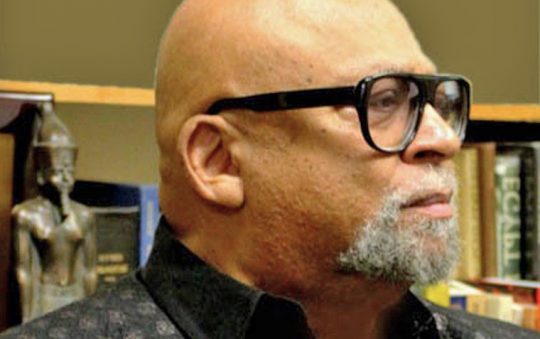

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.