As Juneteenth, now federalized as Juneteenth National Independence Day, takes its place as the main focus among the many emancipation celebrations in this country, it is good to reflect on it and reaffirm constantly its central and sustaining meaning and message for us.

Let us reaffirm at the outset that it is good to celebrate and sing ourselves and our freedom songs. As our Black National Anthem urges us, we must “lift ev’ry voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring, ring with the harmonies of liberty,” i.e., freedom.

And in that celebration and commemoration, we must tell our own sacred narrative, raise and reflect on our long, difficult, demanding and toll-taking struggle for freedom and recommit ourselves to continue the struggle that will ultimately determine the course and content of our lives and our ultimate victory for freedom and good in the world.

Likewise, we must safeguard ourselves and all things dear to us, even our holidays, protecting ourselves and things we value from the ruthless and imperious appropriation and distorted interpretations of others, especially our oppressor. Indeed, one of the greatest challenges of any meaningful holiday in U.S. society is to safeguard it from trivia and trash, from its being reduced to simply and safely fun and games and the addictive consumption of things, from mindless and imitational Americana and Americanism, and from the normalized process and pressure to allow the dominant society to define the holiday in its own image and interest through funding and favors granted, withheld or denied.

And Juneteenth is no exception, having no immunity or exemption from these social processes and common and confusion-inducing practices, and thus we must self-consciously define and defend it on every needed and necessary level.

Our celebration of freedom as a people is a serious and sacred practice, rooted in the memory and reaffirmation of righteous and relentless struggle against the radical evil of unfreedom, especially the Holocaust of enslavement, but also, the savagery of segregation, and the sustained, pervasive and violent oppression of systemic racism.

And it must always be joined with a self-conscious commemoration of the great suffering, sacrifice and loss of lives of our people and a sincere spoken and unspoken commitment to continue the struggle, keep the faith and hold the line until full freedom is an achieved, experienced and lived reality. Thus, if Juneteenth is to truly be such a celebration of freedom, then we must be rightfully attentive to how it is conceived, interpreted and practiced.

As a celebration of our freedom, Juneteenth should and must put our people at the very center of the celebration and commemoration, rightfully raising them up and praising them for their service, sacrifice and struggle in the interest and advancement of our freedom. It must not be reduced to receiving late news on a specific day, but about the history of struggle that brought us to that day and the continuing struggle afterwards.

In a word, Juneteenth must be placed and celebrated, not in isolation, but in the midst of the larger freedom struggle before and after June 19, 1865. Only then can it do honor to the people who lived, served and died on the various battlefields for freedom we were compelled to enter and remain on even today.

And it is in this context of a continuing struggle, an unfinished fight for a still-to-be-realized freedom that we are able to rightfully recognize and find common cause with those who continue the struggle in the honor of our ancestors and in the interest of our own good and the good of future generations.

Moreover, to celebrate Juneteenth rightfully is to have and teach an accurate, agency-respecting and dignity-affirming understanding of the circumstances surrounding the holiday itself. It means rethinking and rejecting the idea that we did not know that Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863; that we did not see and hear about over 150,000 enslaved Africans being brought to Texas to escape the Union army and the freedom however limited that came with it.

It also means rejecting the idea that Galveston, which was a seaport city and a site of constantly bringing and sharing of news and literature by Black sailors, was unaware of the momentous events happening in the country or even of the Union and Confederate battles being waged in and over Galveston since October 1862.

Accepting such a version denies Black consciousness of the changing world and civil war around them, of their enslavers’ increasing desperation, and of their own efforts and eagerness for freedom. In such a reductive conception of our agency, we become absentees of our own history, spectators who read and reference the words and ways of others, and deny, diminish and erase ourselves.

Let us also be able to concede that the arriving general was late not the news and that he declared a freedom that was not real or realized in the simple announcing that all enslaved Africans “are free.” Indeed, the late-coming and limited freedom-announcing general told enslaved Africans that they were “advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages” in an imaginary new labor system of “employer and hired labor.” Moreover, he told them, “They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness there or elsewhere.”

Clearly, it was an announcement of a change of status, from enslaved to emancipated, but it was also a questionable gain when we were at the same time advised to remain quietly where we were before the announcement, not to seek sanctuary or support from the army, and not to be “idle,” unemployed or practice freedom by walking off the plantation and seeking a new life and new form of labor elsewhere.

Such a narrative is deficient, denies our agency and minimal awareness and leaves us with others, i.e., White people, as our central reference and remembrance in our own historical narrative. The need, then, is for us to ask ourselves and our scholars where are we and what did we do in our own history and struggle for freedom, regardless of who else and what else we might add to the narrative and notions of Juneteenth, and then, as always, we must place the celebration and commemoration in the context and critical consideration of our larger liberation struggle.

Finally, let us concede that freedom and emancipation are two different realities and responsibilities. Emancipation is being freed by others; freedom as a practice is a self-liberating activity. Emancipation is granted, but as Nana A. Philip Randolph teaches us, “Freedom is not granted it’s won. Justice is not given it’s extracted.”

Thus, emancipation is received and rightly remembered, but freedom is self-consciously achieved through righteous and relentless struggle of a people who know themselves as ultimately their own liberators, who know the fight for freedom is still not finished, and who understand, teach, celebrate, commemorate and advance the liberating truth and struggle of their own lives and history.

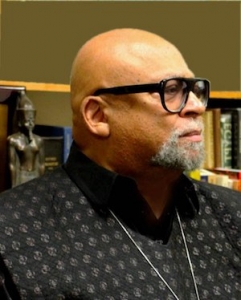

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.