Whatever other lessons we glean from the targeting, accusation, indictment, trial, trashing and conviction of Mark Ridley-Thomas and the dual response to all this by us and others, we know it’s more complex and questionable than is suggested by the deceptive and disarming phrase “justice has been served.”

A follow up article in the L.A. Times bemoans and seems bemused about Black leaders and everyday people paying tribute to a man who has been convicted of “being corrupt in a city rocked by corruption.” But we don’t have to contact the Innocence Project to know everybody convicted ain’t guilty.

Lived or learned lessons in African American history and the law offer abundant evidence difficult to deny or discredit. Indeed, we, as a people, live and come constantly into problematic and precarious contact with the law and we are still at this juncture in U.S. history seeking equal justice under the law with race, class and other diminishing determinants attached to it.

The tributes to Mark Ridley-Thomas occur first, as those offering them asserted, because of his over 30-years of exceptional service and achievement and the refusal to dismiss this dedication and delivery of good to the community, city, county and state because of what is considered a questionable and unjust conviction.

Indeed, they refuse to throw Mark under the bus or “mama from the train” because of a change in circumstance accompanied by what is perceived as political prosecution and a predatory practice of racialized law. And it was for them a sad day personally and collectively, as well as for the community, the city and society.

Now, the concept and practice of racialized law is key here. For it means recognizing that society has racialized crime and criminalized a race. That is to say, society sees and poses crime as a racial characteristic and problem, and the race of Black people as a problem, itself, translating this psychological racist disorder into public policy and socially sanctioned practice with devastating effects.

To talk of a political prosecution is to speak of the use of the law to discipline, detain, discredit and destroy opponents, rivals, rebels and those seen as problematic and insufficiently servile, deferential, and supportive of powerful others’ agendas. To talk of predatory practice of racialized law is to speak of targeting and preying on those disfavored and vulnerable, using racialized conceptions and practices of the law. And to racialize is to define everything in terms of race, a socio-biological category created and used to assign human worth and social status using Whites as the model.

Thus, there is the racialization of crime (called Black crime) and the criminalization of the race (Black people). Moreover, since the founding of the country, the law has been an instrument of oppression, i.e., legalizing and enforcing genocide, enslavement, segregation and various other kinds of repression, discrimination and destruction.

There was the suggestion that those standing in solidarity with Ridley-Thomas were doing it because of his race. It is a practice of double standard “reasoning,” questioning our sense of communal solidarity in resistance to what we perceive as a problematic and unjust indictment and conviction by reducing it to simple racial identification.

This is not done for White ethnics and others and is a way to racialize and reductively translate Black people’s capacity and customary practice of critical judgment of the just and unjust. Also, it hides their commitment to real justice and criticizes them for not uncritically accepting established-order definitions of justice and racialized interpretations of reality.

Anyone with a modicum of awareness can see that there is an abundance of examples of selective prosecution, especially along racial and class lines; that there is a lingering and sickening scent of selective moral concern about crime and corruption in racial and racialized terms; and there is a greater eagerness and animosity and too often lesser evidence in the targeting, pursuit, indictment, trial, trashing and conviction of Black people. Thus, in a real sense, as many see it, it’s not just about Ridley-Thomas, but a national problem of racialized selective moral concern and predatory pursuit of Black leaders in particular and Black people as a whole.

It is a communal sensibility, mode of reasoning and ongoing concern about achieving racial justice rooted, not in an abstract concept of race, but in a lived and living experience of centuries of racialized and racist domination, deprivation and degradation and a deep enduring commitment to questioning and ending all forms of oppression whether official, unofficial or otherwise.

The Black community leaders and members who stand in solidarity with Mark Ridley-Thomas do so also, then, as a commitment to communal solidarity in struggle against injustice and oppression. We have both the right and responsibility to be concerned about issues of justice, equality of treatment, and rightful recognition of service and achievement of members of our community.

And we have no obligation to justify our communal concern for justice and equal treatment or accept without critical questioning what is perceived as injustice and unequal treatment, even if it is carried out under the color and camouflage of law.

Finally, there is here a sense of shared future or shared fate, an achievement of justice for everyone or no real justice for anyone. For indeed our freedom, justice and equality are indivisible shared human goods. As our honored ancestors taught, if you see an intruder in your neighbor’s house, you should confront and stop him, for if you allow him to intrude unchallenged in your neighbor’s house today, tomorrow you will find him in yours.

Our struggle in this country has been from the beginning to expand the realm of freedom, justice and equality so that it is an inclusive and shared good for everyone. And we cannot achieve this goal if we surrender our right and responsibility to question and confront, to think with our own minds, speak with our own mouth, and be concerned and care with our own hearing heart with its rightful attentiveness, empathetic understanding, and appropriate action as requested or required.

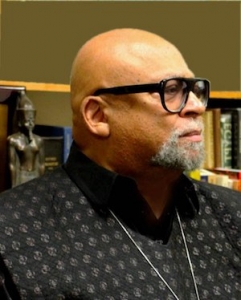

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.