“Henry Aaron, in the second inning walked and scored. He’s sittin’ on 714,” said Braves announcer Milo Hamilton calling the game on WSB Radio. “Here’s the pitch by Downing. Swinging. There’s a drive into left-center field. That ball is gonna be-eee … Outta here! It’s gone! It’s 715! There’s a new home run champion of all time, and it’s Henry Aaron! The fireworks are going. Henry Aaron is coming around third. His teammates are at home plate. And listen to this crowd!”

April 8, 1974—The first home game of the season for the Atlanta Braves, with a packed crowd of 53,775 people in attendance. It is the fourth inning, and Al Downing was pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Downing throws a slider, and Hank “Hammer” Aaron makes history hammering home run number 715, surpassing Babe Ruth for all-time career home runs.

“I had creeped up on the plate just a little bit… that pitch honed the outside part of the plate, but it hung right down the middle and I was able to get my bat on it,” said Aaron.

The ball flew into the Braves’ bullpen, Dodgers outfielder Bill Buckner nearly went over the outfield fence trying to catch it. The crowd cheers senselessly, cannons blasted, fireworks burst to the sky in celebration. As Aaron rounds third base, a swell of teammates, media, as well as his parents all meet him at home plate.

Henry Louis Aaron was born February 5, 1934, in Mobile, Alabama to Herbert and Estella Aaron. The Aarons lived in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Mobile they called “Down the Bay,” but Henry spent most of his formative years in the nearby district of Toulminville. Young Henry was one of eight siblings. His younger brother Tommie later also played in the majors, and for what it’s worth—the two brothers still hold the record for the most career home runs by a pair of siblings—768 home runs.

As a child he was fully entrenched in what was the most viciously segregated section of America. Aaron once recalled, “I remember many nights my brother and I would be out playing baseball… [My mother] would tell all of us ‘Come in the house and get under the bed!’ About 10 minutes later, we would have the Ku Klux Klan coming through intimidating and throwing firebombs and things like that. That is what really kind of set you apart and say just because your skin is little different, they were going to treat you a little different.”

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson, at the age of 28, stepped onto Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, and historically became the first African American player to play Major League Baseball. Two years later, the fifteen-year-old Aaron became very much influenced by the accomplishments of Robinson, and tried out for the Brooklyn Dodgers; however, did not earn a contract offer.

Entering the 1950’s, at 18-years-old, Henry Aaron was signed by the Negro American League’s Indianapolis Clowns earning $200 a month. During that season, his contract was sold for $10,000 to the Boston Brave’s before the team relocated to Milwaukee.

He worked his way up, and in 1953, Aaron was promoted to the Jacksonville Braves, becoming one of the first Black players to integrate the South Atlantic League. Aarons tribulations with racism would be ongoing throughout his career; however, he stayed focused and took his aggressions out on the baseball field. That season, Aaron won the MVP and led the Class-A affiliate league in runs (115), hits (208), doubles (36), RBIs (125), total bases (338), and batting average (.362).

Aaron’s talent was undeniable. In 1954, he attended spring training camp with the major league club. Some reports said that Aaron hit the ball so hard that management could hear the crack of his bat from the inside the clubhouse.

Author Roger Kahn said to Sports Century, “Spring Training the Dodgers and the Braves traveled together. Aaron was on second base, and between pitches [Jackie] Robinson walked over and shoved some dirt into [Aaron’s] shoes. Here was a young [Hank Aaron] and the great Jackie Robinson shoving dirt into his shoes. ‘What are you doing’ said Aaron, ‘Well I have to do something to slow you down,’ Jackie said.”

During a spring training scrimmage, left fielder Bobby Thomson fractured his ankle while sliding into second base. With no options, the team signed him to a major league contract. Aaron made his major league debut wearing number 5 on his jersey on April 13th. However, he went hitless his first five-at-bats against the Cincinnati Reds. With a batting average of .280 with 13 home runs, he suffered a fractured ankle the following September.

Coming back from injury, he changed his number to 44, in which some recognize as his “lucky number.” Call it coincidence, after the number change Aaron went on to hit 44 home runs in four different seasons. Aaron surely entered his athletic prime in the 1950’s; in 1955, hitting a batting average of .314 with 27 home runs and 106 RBIs; or 1957, in Milwaukee, when he hit a two-run walk-off home run against the Cardinals, clinching the pennant for the Braves, and going on to win the World Series against the New York Yankees.

In 1966, the Braves moved to Atlanta during the pinnacle of the Civil Rights Movement. At the time, of reintegration of Whites and Blacks, 100 years after reconstruction era. Though, Aaron spent the bulk of his career in relative obscurity concerning media popularity, he burned with a type of hard gem-like flame. His appeal slowly grew on the public when his reputation developed into the home run hitter who would surpass Babe Ruth’s untouchable record.

Dick Gregory once said, “That record didn’t mean nothing to Black folks that wasn’t into sports. It was when they added the racial thing to it, then for the first time we knew it was important.

With Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death in 1968, the riots in 1969 the White backlash after the civil rights movement, and the Braves playing baseball in the heart of the civil rights movement—Aaron received death threats surrounding his play.

Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully addressed the controversy leading up to Aaron’s recording setting hit, “What a marvelous moment for baseball; what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron… And for the first time in a long time, that poker face in Aaron shows the tremendous strain and relief of what it must have been like to live with for the past several months.”

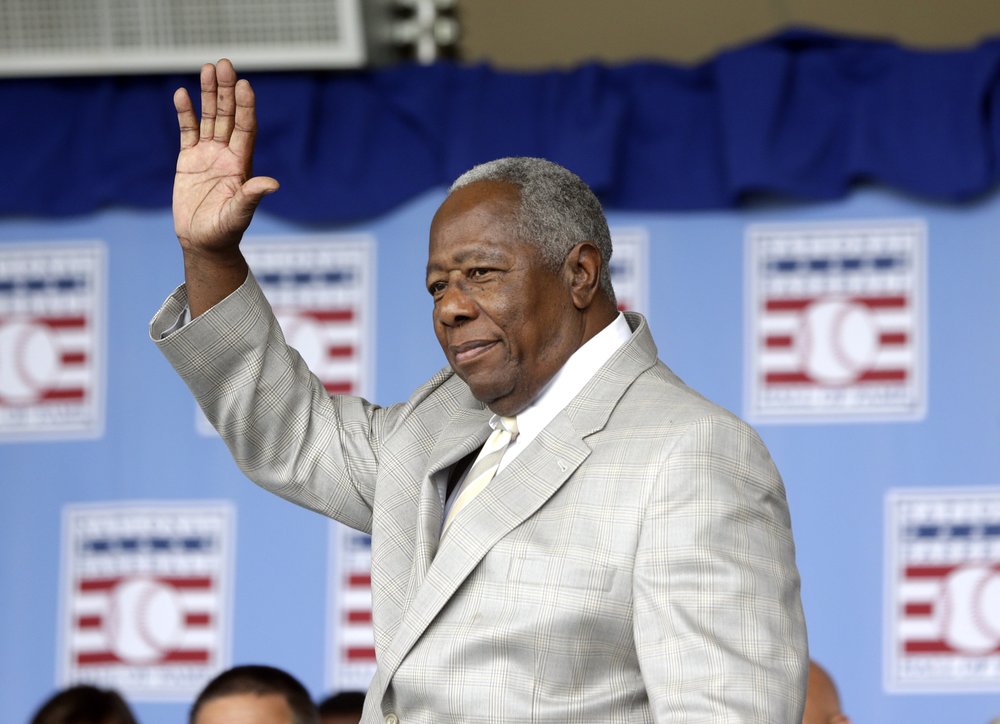

Though, Aaron spent the bulk of his 23-year career in relative obscurity concerning media popularity, he burned with a type of hard gem-like flame. Aaron who drove in more runs than Lou Gehrig, scored more runs than Willie Mays and had over 12 more miles worth of bases than the runner up Stan Musial, and even if you take away every single home run, he still had 3,000 hits. He is a Baseball Hall of Famer—class of 1982, he was awarded with the Presidential Medal of Freedom from former President George W. Bush, he was awarded with the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP in 1976, and countless other accolades.

The life and legacy of Hank Aaron transcended sports. He spoke for peace and shined a light a broken system that still rears its head through prejudice. Aaron inspired generation to chase their dream in a manner of grace by discovering his inner strength.

Aaron once said, “As a little boy growing up in Mobile, Alabama, I dreamed of playing baseball. I wanted to play baseball so bad but had nobody to help me, so I just thought that if I ever got into a position to help other children, regardless of whatever color they may be, and [help] them chase their dream, I was going to do anything that I possibly could… That’s why we have the Chasing the Dream Foundation.”

Hank Aaron’s Chasing the Foundation promotes youth development by funding programs that support the achievements of the youth struggling with limited opportunities. Enabling them to develop their individual talents to pursue their dreams.