One may watch the viral video of UCLA gymnast Nia Dennis’ Beyoncé-inspired floor exercise or celebrate the news of South Carolina head coach Dawn Staley becoming the AP Women’s Basketball Coach of the Year and take for granted the progress women’s athletics has made in the past 50 years.

When Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 was passed, academic institutions had to ensure equality in the federal funding of activities for men and women. Prior to that, women’s athletic activities go little to no funding.

During the Civil Rights Movement and prior, African American female athletes felt the sting of their double-minority, being overlooked in the media and occasionally going unrecognized by their male counterparts.

Yet, they found success in collegiate athletics and beyond. An example of such is the story of Wyomia Tyus.

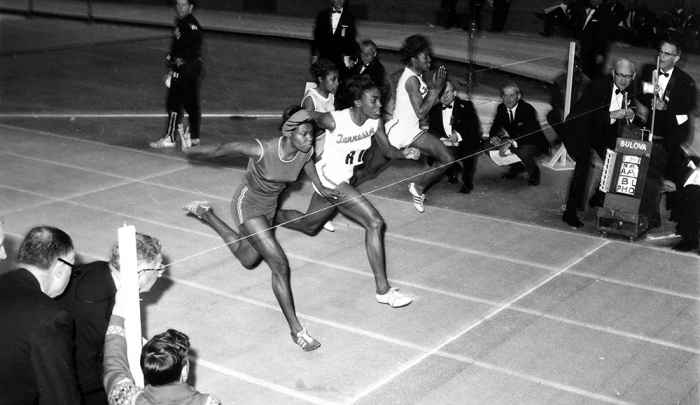

Griffin, Georgia native Tyus rose into prominence a decade before Title IX was passed as a sprinter for the Tennessee State Tigerbelles, the successful HBCU track and field team that produced Wilma Rudolph.

“They’re known for having fast women, on the field that is,” Tyus joked in an interview with the L.A. Sentinel, but her statement could not be truer. Tennessee State housed over 40 Olympians who won 23 medals.

“13 of those medals were gold,” Tyus said

Tyus was the first Olympian to win two consecutive gold medals in the 100m when she won in the 1964 Tokyo Games and in the 1968 Mexico City Games. She chronicled her track and field career in her autobiography “Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story.”

While she made those achievements, collegiate sports provided few to no options for women.

“It’s not like it is now, young women have the opportunity to go to any university or college they want and any sport that want and then all the encouragement and everything young girls and young women get nowadays,” Tyus said. “Tennessee State, at one point, was the only school that was giving athletic scholarships to women in the whole USA.”

In the book “Tigerbelle,” Tyus noted how her coach, Ed Temple, said the Tennessee State track and field program “was Title IX before Title IX.” Temple started coaching at Tennessee State in 1950 at a time where intramural sports were a standard for women, intercollegiate competition was uncommon. Yet, Temple worked to galvanize women in track and field at the time.

Discrimination came in different forms, from social and familial settings to the media.

“I grew up with people saying ‘You’re not gonna be able to have children because you’re competing,’ ‘you’re gonna have muscles, men don’t like muscles,’ all those kinds of things,” Tyus said. “For me, it did not bother me.”

“Tigerbelle” co-author Elizabeth Terzakis wrote how Sport Illustrated featured the all-White Texas Track Club instead of the Tigerbelles in 1964. The Texas Track club was touted for their hairstyles and makeup they wore during track meets over their athletic merit.

After winning a gold medal in the 4x100m relay at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Tyus dedicated her medal to John Carlos and Tommie Smith in the wake of their medal stand protest. The Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), the organization that Carlos and Smith were members of, did not include any Black female athletes in their projects.

Regardless of the struggles she faced, she remained positive and allowed her athleticism to pave a way for generations of female athletes.

“We were at a time not only were we at Tennessee State, women weren’t encouraged to do all those things, but I grew up during the Jim Crow Era,” Tyus said. “There were so many things that if you look at it, if you start thinking about it, those things were against you, but they just made me a stronger person.”