Graphic (Amen Oyiboke/LA Sentinel)

On a rainy Christmas Eve in 1988, South Los Angeles native Toni Bazley was on her way home from work when she noticed a mother and two children waiting at a bus stop.

“It was close to 10 o’clock and I couldn’t just drive by the family without offering a ride to them. It was Christmas Eve and no one deserved to wait in the rain,” said Bazley. She remembered asking the woman if she wanted a ride home and pulled into the closest gas station to let the small family enter her 1981 Toyota Corolla.

Bazley continued southbound on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and made a right turn on Vermont. That’s when her good deed took the wrong turn.

“I got into a hit-and-run accident with a drunk driver on the intersection of Vermont and Florence. The driver slammed into me so hard that my car hit a pole and folded,” said Bazley. The mother and children were unharmed, but Bazley suffered from head injuries and was rushed to Martin Luther King Jr./Drew hospital.

Bazley quoted her experience to be different than those who negatively spoke about MLK hospital during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, calling it “Killer King”.

“I know people had horrible mentalities about the hospital because of some things that occurred there. Honestly, it affected my thoughts too until I had my accident,” said Bazley.

But, Bazley maintains that her experience was a positive one.

“The doctor at MLK did a wonderful job stitching me up and calming me down,” Bazley said.

South LA resident Toni Bazley believes the new hospital is the right steps in the right direction for South LA and healthcare services. (Amen Oyiboke/LA Sentinel)

Eight days after the riot then-Governor Edmund Brown assembled an investigation group called the McCone Commission. The group held the responsibility of exploring the root causes of the uprising and made recommendations to Congress on what some of the remedies should be to help residents of South L.A.

The commission released the 1965 McCone Report, which stated that upgrading healthcare services in South L.A. would increase the chances of overall improvement of health conditions in residents of the area, who felt neglected in resources for medical attention. In response to that report, then 8th District Los Angeles County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn made it his mission to bring emergency healthcare to the area.

The hospital was founded, as a response to the Watts Riots in honor of civil rights pioneer Martin Luther King Jr. It was a sign of hope and change for a city recuperating from violence and low quality medical services. The hospital then opened in 1972 to the general public and was licensed for 461 beds.

“A lot of people believed the community of Watts didn’t need a hospital, but my father believed it,” said Rep. Janice Hahn (D-Los Angeles), daughter of the late Kenneth Hahn.

“Eventually, through a lot of effort my father was able to get put on the ballot to have the people of the county vote to issue money for the hospital. He always believed that everyone deserved proper healthcare services. The lack of hospital care was really one of the biggest holes in the community.”

The healthcare needs of South L.A., also known as Service Planning Area 6, not only included emergency and trauma services, but also inpatient services, primary care and specialty services that were in high demand but in short supply, according to L.A. County’s Department of Health Services.

“When my father was there it was a really good hospital. He always made sure they had all the equipment it needed to be a good hospital,” said Hahn.

However, reports had shown that problems in patient lapses started soon after the hospital opened. In 2003, the hospital faced crises like untimely patient deaths due to neglect. In February of 2005, the hospital lost its seal of approval from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. King/Drew hospital soon became the smallest of the county’s four general hospitals decreasing down to 357 beds by 2006.

“I started working at King hospital when the name ‘Killer King’ was given to us. That name preceded the opening of the hospital,” said Samuel Shacks, former vice chancellor of pediatrics at King/Drew. “That name was not an earned name it was a given name. We had a very developed staff and good doctors who knew how to tackle the difficult area we were in.”

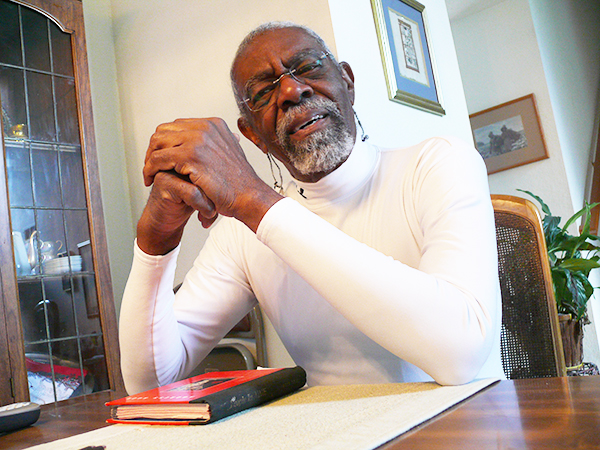

Former pediatrics doctor at Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Hospital Samuel Shacks served his position at the hospital until 2006. He believes the name “Killer King,” was created to cause a biased mindset of the facility. (Amen Oyiboke/LA Sentinel)

Shacks started his residency at King/Drew in 1977 and took on a faculty position in 1982 where he stayed at the hospital for 19 years. “Many people in the area ignored King and went outside our corridor to visit other hospitals. People did not fight to speak up about the troubles we faced servicing the area. They always thought it was better for them to not be at King,” said Shacks.

Reports of a grossly inadequate facility and improper incidents exposed by the Los Angeles Times from 2004-2007 showed a lack in general upkeep in the King/Drew Hospital. “That is what people should expect when you are the least resourced county hospital. We also had to fight for resources in a way that others could get and a lot of equipment we received came used,” said Shacks.

After the articles were published the hospital closed its doors for good in 2007. For eight years nearly 1.2 million residents of the surrounding area have gone without an emergency care facility in their community. However, things will reportedly change this year.

After its closing, county officials chose to hand the hospital over to a non-profit chain, Martin Luther King Healthcare Corporation, to reevaluate and remodel its infrastructure. The new Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital (MLKCH) is scheduled to treat patients in late spring, according to Al Arimendez the Marketing and Communications Manager of MLKCH.

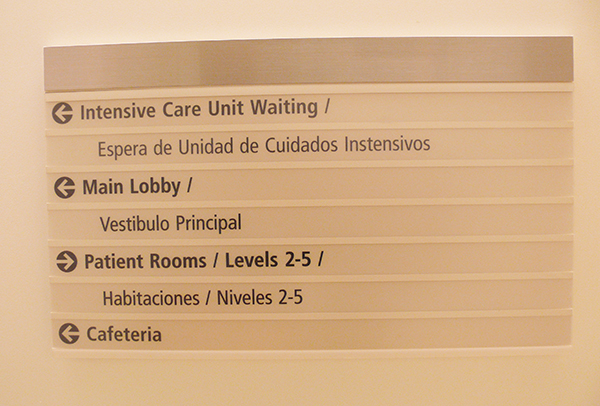

Multiple signs throughout the hospital direct patients and healthcare staff to the 16-inpatient services provided. (Amen Oyiboke/LA Sentinel)

“We are a phase hospital, so we have to go through licensing and training before we can do anything. That’s why we are really careful about giving exact opening dates because it really isn’t our call. It depends on our licenser requirements,” said Arimendez.

Opening dates have been repeatedly set back and Arimendez stated that it’s due to the non-profit funding. “We are a 501c3 so our money is coming from other sources,” he said. The $284 million hospital is equipped with five levels of restructured rooms, brand new medical equipment and 16 departmental services. Hospital officials state that the new hospital will give baseline services that the area has lacked for the past eight years.

“The new hospital is designed to meet the needs of the area it serves. The hospital will have new equipment, specialists, new physicians 24/7 and we will work with people outside of the hospital to help patients transition in and out of the facility,” said Dr. Elaine Batchlor, President and Chief Executive Officer of MLK Community Hospital.

Each bedside has installed new hospital monitors and electronic touch equipment. (Amen Oyiboke/LA Sentinel)

One of the benefits that the hospital will have is recruiting new physicians and specialists to add to the hospital and that will help the area,” said Batchlor.

But for some residents the new hospital just isn’t enough.

“A new facility is a good thing and I’m not against that. But, what happens to the people who need trauma care?” said community activist Larry Aubry.

“We cannot continue to be satisfied with what is mediocre in South L.A. The norm is detrimental to our health,” said Aubrey.

Trauma and stroke victims will have to travel to three and 10 miles away to St. Francis Medical Center or Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Still, hospital officials hope that keeping the local residents aware of provided services will prevent victims needing trauma care from coming.

“Healthcare has changed a lot over the past 15 years. We are focusing on preventative wellness programs and services to help minimize rescue care,” said Batchlor. “This helps prevent their health deteriorating to the point where they need emergency care.”

The shaky past of King/Drew hospital continues to raise concern about what is to come for South L.A.’s new MLKCH healthcare services however, residents like Bazley hope the new center will bring the hope the community has been missing for eight years.

“I’m happy that the black and brown community has a place to go for care. People can complain all they want, but we have to recognize that we just received a brand new facility that will help us all,” said Bazley.

These pieces are part of a USC Annenberg directed collaboration investigating social change in South Los Angeles 50 years after the Watts Riots. All project stories can be found at www.wattsrevisited.org