Fifty years ago, on April 4, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on the balcony of Memphis’ Lorraine Hotel and this Wednesday’s anniversary was a time for the nation to reflect on the Civil Rights leader’s ideology. So, what does Dr. King mean to America today, asked reporters, citizens and activists across the United States. Answers varied from King’s legacy still being determined, to there being a need to revive his dedication to making societal changes that promote justice, equality and freedom.

“Like many in my generation, I was raised to view myself as inheriting rights and privileges for which the previous generations had struggled and sacrificed,” said filmmaker Bree Newsome, who emphasized to reporters at CNN that what was “old should be new again.”

Black millennials cannot take their freedoms for granted, she said.

“The expectation that we should have equality and the realization that we still didn’t have it, led to Black millennials rising up in mass protest during the latter half of the Obama administration … Access to public accommodations is the only civil rights issue of the 1960s for which we aren’t still actively organizing and protesting. Voting, education, police brutality, housing and wealth inequality remain central issues of modern civil rights and black liberation. Understanding that King’s mission was violently interrupted in 1968 is key to understanding where we find the nation in 2018: deeply divided along racial lines with great unrest, multiple social justice movements occurring and a government openly hostile to black protest,” Newsome said.

“I never even talked about it because I do — I get so emotional,” Mary Ellen Ford, who was a witness to King’s assassination in 1968, told NBC’s “Today”.

Ford had been part of the now historically significant photo that showed witnesses pointing toward the direction of gunfire. She was an employee at the Lorraine Hotel and was working when she and others heard gunshots ring out. In the photo she was a part of a group of onlookers in the hotel’s parking lot at the time, police marking her as “witness number 43.”

“I grew up (that day) because it was something I’d never seen before,” she said.

Dr. King had been in Memphis to support a sanitation workers’ strike there, the night before giving his “promised land” speech. The speech eerily seemed to predict his death.

“I’ve seen the promised land,” King said.

“I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord…”

Then, the following evening around 6 p.m. he and his associates had been on their way to dinner when he was fatally shot, while standing on the balcony outside his second-story room, a bullet striking him in the jaw and severing his spinal cord. King was pronounced dead after his arrival at a Memphis hospital. He was 39-years-old.

Shortly before, Dr. King had been focused on the problem of economic inequality in America and the suffering that came with it. He had organized a Poor People’s Campaign and had been to Memphis just weeks earlier for the sanitation workers. But a protest there ended in violence and a protestor was killed.

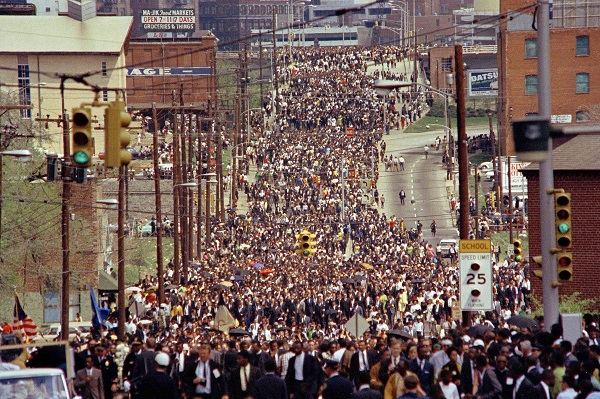

King left the city but vowed to return. Parts of the country erupted as news of his death spread, riots breaking out in a myriad of cities. On April 9, King was laid to rest in his hometown of Atlanta, Georgia.

“There’s certainly a lot of respect for the significance of [this anniversary],” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas who traveled to Memphis this week to join the commemoration.

Ridley-Thomas was 13-years-old at the time.

“I was struck by the impact of his death,” he told the Sentinel this week.

“To be here, now, 50 years later is really quite moving. We have a lot of unfinished business related to justice, peace and human dignity. But the nation owes a great debt of gratitude to Dr. King and his family and all of those continuing to fight for democracy.”

Urban League President Marc Morial, agrees that King’s mission is one that needs still be fulfilled.

“King’s Poor People’s Campaign floundered in the wake of his death, and Johnson’s War on Poverty seems to have become, in the hands of later presidents, a War on the Poor,” he told reporters this week.

“Income inequality has skyrocketed since the 1970s, and the buying power of the minimum wage has sunk.

“Now, a new generation of activists has revived King’s vision, and the Poor People’s Campaign, led by the Rev. William J. Barber, has begun a series of rallies and protests. Young people across the nation have risen up to protest gun violence — in a sense, echoing King’s condemnation of the Vietnam War.

“Fifty years after King’s death, we may be at a crossroads, but to paraphrase a favorite line of his: I do believe all roads lead, eventually, to justice…”

Said one of King’s closest associates Reverend Jesse Jackson, “We owe it to Dr. King — and to our children and grandchildren — to commemorate the man in full: a radical, ecumenical, antiwar, pro-immigrant and scholarly champion of the poor who spent much more time marching and going to jail for liberation and justice than he ever spent dreaming about it…”