This is a Father’s Day message for Black fathers, African fathers, made more urgent and needed by the constantly changing and ever challenging times in which we strive to live good lives, do our work well, and wage victorious struggles of smaller and larger kinds.

It is a message of homage and hope, of cherishing and challenging, of continuing the struggle, keeping the faith, and holding the line for a shared African and human good and the sustained well-being of the world.

Fatherhood, like our life, work and struggle, is an Ujima project, a collective work and a collective responsibility and all are needed for this awesome and indispensable work and joy we call fatherhood, as it is for motherhood and parenting as a whole. And so, we pay rightful homage to the mothers of our children and all others who made our fatherhood possible and aid in sustaining it.

This special day is marked and made meaningful by the honors, praises and reaffirmations of the good we strive to do, the joy we struggle to bring, the guidance we make great efforts to give, and the protection and the psychological, moral and material support we work so hard to provide in varied ways.

Related Stories:

America in Crisis Between Massacres and Myths: Seeking a Moral Compass and Commitment to Change

African Liberation Day and the Nguzo Saba: Principles and Practices for Liberating Struggle

Thus, it is also a special time for those who love and care to come together to bear and share witness to the truth of our measure and meaning as fathers, indeed as men among men, men among women, and men honoring the roles and responsibilities as fathers of sons and daughters, as members of our families and communities, and as co-combatants in the unfinished struggle of our people for freedom, justice and good in the world.

But again, this day is not simply a day for fathers in the abstract and isolated from our families and people or the struggles we wage for good in our lives and the world. Indeed, it is in a larger sense a homage to us all, the whole people who made us men and fathers possible. It is a celebration like Mother’s Day, Kwanzaa, Black History Month and the Days of our Heroes and Heroes, another day of remembrance, reflection, reaffirmation, and recommitment to the Good in the way we live our lives, do our work and wage our struggles.

And here we realize our Father’s Day is a father’s day celebrated in the midst of oppression and resistance, an ongoing struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves, secure justice, repair damage done, retrieve and rebuild on the best of who we are as fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, men and women, and honor the legacy of love, struggle, excellence and achievement left us by our honored ancestors.

May we honor this great legacy by living it. And may the struggles we wage always add to our honor and lead to our victory as the sacred teachings of the Odu Ifa counsel and encourage us. Indeed, this is a central point and part of this message, given by our ancestors Nanas Thurman, Brooks and Burroughs.

We – the people who have ridden the storms and hurricanes of history, constantly conducted our blooming in countless whirlwinds and regularly specialize in the wholly impossible – we cannot be defeated. Only if we, ourselves, surrender are we truly subdued.

We pay homage here to all Black fathers, past and present, and those yet to come: To the warriors and workers for a world, battling and building at the same time; to the devoted lovers and heavy lifters, seemingly sometimes bearing the weight of the world on our shoulders. To the givers, guardians and guides, the protectors and providers without denying the shared roles with mothers.

We pay homage also to the ordinary and everyday ones and the exceptional and extraordinary ones, to those successful and those still striving and struggling for the good, the right and the possible, regardless.

Indeed, we pay homage also to those who would, if they could; would have, if they could have; who tried, but were disabled, discouraged or crushed by the radical evil of racist and other oppressions. We cannot forget them or believe all is lost, but must constantly reach out to those less able, those on the road to ruin and those who stumble, fall and need help on rising and raising themselves.

For we are always humbly aware that, as our ancestors taught, there, but by the grace and good of the Divine and others, we too might be. And this too, as the ancestors instructed us in the Husia, we know that “the good we do for others we are also doing for ourselves.”

For we are building and strengthening the good community and world we all want and deserve to live in and leave as a worthy legacy for those who come after us.

Our task then is to speak the truth to our people, to men and women, to girls and boys, about who we are. And this truth speaking must be in both word and deed, an expression and embodiment of principles and practices that declare and demonstrate we are fathers in the fullest sense of the word.

Here, we again stress practice and repeat that practice proves and makes possible everything. Whether it’s in the matter of love or life, friendship, faith or fatherhood, it is our practice that determines the quality and demonstrates the reality of it.

To talk about practice that expresses and embodies our identity and commitment as fathers is to engage the question of a father’s presence in the lives of our sons and daughters, in our families, our communities, and our struggle. Clearly, one of the most compelling calls and continuing needs of Black fathers is to be present in concrete, caring and practical ways.

Indeed, to really be a father, to exist as a father is to be present. In Swahili, the word to exist or be present, kuwepo (koo-way’-poh), literally means to be in a place, to occupy space, to be somewhere. And that “somewhere” for Black fathers must be in the family, in the community and in the struggle.

Now the concept of being present must not be reduced to being present only in physical form. For persons can be physically there and still be nonfunctional or dysfunctional. So, presence does not mean just being in place without feeling or function. On the contrary, it must be a caring and active practice.

It means being in the home, but also in the heart and minds of our children and other family members because of the known and appreciated good we do and represent for them. It means being a felt presence, even in our physical absence. Indeed, in such a context of a felt presence in our absence, there are signs and substance of our being there – a continuing imprint and impact.

Naturally, the ideal situation is for fathers to be physically, psychologically and functionally present. But we know there are personal and social conditions that often do not facilitate, foster, support or even allow our physical presence. So many men are away from their children through separation, divorce, and distance occasioned by requirements of residence, incarceration, work, and service in other places in the country or overseas.

But we must still do what we can to be present in caring and active ways, still present in ways we can – in communication, counsel, material support, nurturers, guardians, guides and teachers of the good, the right and the possible as reflected in the Nguzo Saba (The Seven Principles).

And even as we are – what Nana Ida B. Wells calls on Black women and by extension all of us to be – “a strong bright presence” in our families, we must also be so for and in our communities and struggle. For we must be models and mirrors of our ancestors who lifted up the light that lasts, being sun and moon, day and night, grounding us in our highest moral and spiritual values and showing us the way forward.

We must be worthy partners as fathers and men, in life, love, work and struggle, warriors and workers for a new world. And we must, as Nana August Wilson taught in the Kawaida tradition, stand “squarely on the self-defining ground” of our culture in which we, our people, are the moral, spiritual and intellectual center.

For only from this vantage point can we define and conduct ourselves in the dignity-affirming, life-enhancing and world-preserving ways of our ancestors, ever concerned with the practice and promise of shared good in the world.

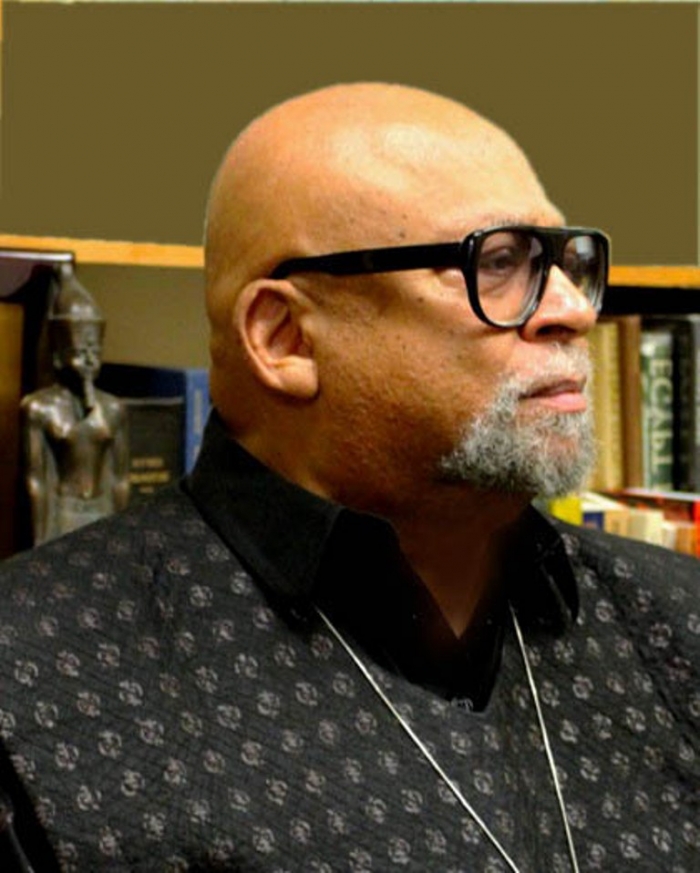

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.