Focusing on culturally tailored literacy and education is going to be the best bet for African Americans to combat Alzheimer’s Disease, an issue that affects the older community two to three times higher than their white counterparts, according researchers. For her part, Dr. Karen Lincoln, an associate professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work and founder of Advocates for African American Elders at the USC Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging, has conducted the Brain Works study, which highlights that fact. Alzheimer’s is the fourth leading cause of death among African American older adults.

There is no cure for AD, but experts agree that earlier diagnosis provides greater treatment and planning options — including organizing ongoing care and planning for financial and social well-being — for patients and caregivers, Lincoln said.

“Alzheimer’s education is important for everyone,” she said.

“However, increasing Alzheimer’s literacy among African-Americans is crucial for increasing their awareness of their personal risk for the disease, improving care, reducing disparities and ultimately enhancing the quality of life of people diagnosed and their caregivers.”

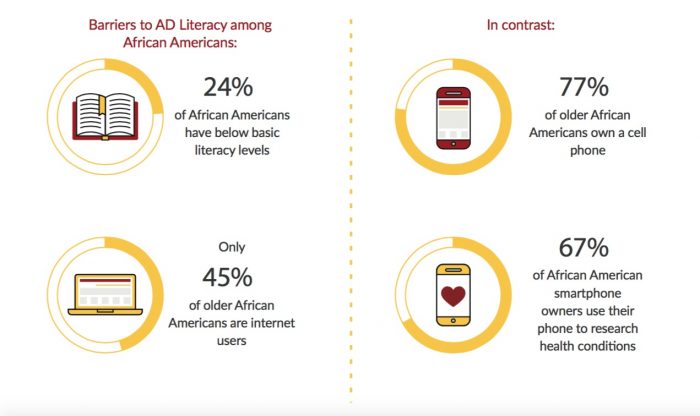

Researchers, explained Lincoln, say traditional methods of educating older Americans and their caregivers — print communication and the internet — are missing the mark. One in four African-Americans have below basic literacy levels and less than half of older African-Americans are internet users. In contrast, 77 percent of older African-Americans and 92 percent of African-American adults overall own a cellphone, providing what the USC research team called a “level playing field” and the means to reach its target audience.

For the study, USC researchers enrolled 225 African-Americans ages 45 years and over from senior centers, churches, senior residential communities and social clubs in Los Angeles. They randomly assigned participants to three different interventions and conducted pre- and post-intervention surveys to evaluate their effectiveness.

First, one group of participants received standard printed materials on Alzheimer’s and attended a 60-minute, culturally tailored talk show format event held at a large community site. Second, another group received the materials, attended the talk show and also received daily text messages designed to increase knowledge about Alzheimer’s by providing “nudges” to engage in healthy brain behaviors.

Third, a different group received the materials, attended the talk show event and received text messages that addressed the same kind of information as the general text messages but used colloquialisms, language and style that better resonated with older African-Americans.

In another culturally tailored message designed to encourage mental stimulation, researchers substituted a suggestion in the general text messages to play Scrabble and Sudoku with a culturally tailored suggestion to play games popular in the African-American community such as bid whist, dominoes or spades.

While all three groups had measurable increases in Alzheimer’s literacy from baseline (measured by the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale, a set of 30 true/false items), the group that received the culturally tailored text messages had the greatest increases in literacy.

“There are no other interventions I’m aware of that focus on Alzheimer’s disease literacy in African-Americans,” Lincoln said. “In addition to being culturally appropriate and tailored, it’s fairly low-tech, which is very important as we’re talking on average about a low-literate, low-computer-use population.”

As a social worker, Lincoln started a program through which she works with a lot of seniors in South Los Angeles, directing them to resources and providing information and education. Through her work, she started to see a disturbing trend. She began to notice that more and more people were looking for help with loved ones whose mental health was deteriorating.

But they were looking for help that was difficult to find. Some African-Americans delay consulting a physician about memory problems, for instance, by as long as seven years, according to Patricia Clark and colleagues, at Emory University. Reasons include their own or their family’s inability to recognize the symptoms, low perceived threat of getting Alzheimer’s or their belief that the symptoms of Alzheimer’s are just part of the aging process.

“We started to see a lot of people looking for help with things like housing, medical resources, etc. and I thought, ‘We really need to get to people before they get to a crisis state.’ [African Americans] are more likely to reach crisis state, diagnosed at later stages when it’s less manageable. We were dealing with a lot of things like senior fraud for instance so we started to educate people on what signs to look for…”

Then, the crisis hit home.

“About two years ago my mom started to engage in some interesting behaviors,” Lincoln recalled.

“I was being told [by my sister who lives in Northern California] about some of things going on and they were being explained away.

[For instance], she started to purchase a lot of unnecessary things from television. My sister noticed she was trying to get a reverse mortgage on her house. As a result of that, we had to find somewhere for her to move because of all the expenses that she had racked up that were attached to her mortgage. And then, here hygiene started to deteriorate, which is another sign…”

Fortunately, for Lincoln’s family her mother was able to get the help she needed. But others haven’t been as lucky. Over 5 million Americans suffer and of those a little over 40 percent are black.

“The likelihood of suffering Alzheimer’s is up to three times as great among African-Americans than whites. If I didn’t actually know these facts, I could have guessed based on my work with older African-Americans and their families in South Los Angeles and other under-resourced, underserved communities,” Lincoln wrote in a recent commentary about her experiences.

“Of the many crisis-oriented requests I receive as a social worker, the most common involve the effects of memory loss on a person’s ability to live independently and their family’s inability to care for them. Consider scenarios where an aging parent repeatedly calls the police for no reason or falls into extreme debt for inexplicable purchases or scams. Housing issues come up a great deal: Adult children seek to understand what help Social Security can give (none) and face considering quitting their job when realizing they and their parents can’t afford $7,000-a-month for memory care, special care living units designed for Alzheimer’s or dementia patients. Let’s not even mention latchkey parents; seriously, don’t because health care providers are duty bound to report that.

“While, the causes of Alzheimer’s are relatively unknown, the higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s among African-Americans has been attributed to a higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension and poverty – all risk factors for Alzheimer’s. However, few studies focus on risk-reduction factors such as Alzheimer’s education…”

Additional study authors are Tiffany W. Chow, professor of clinical neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and director of clinical monitoring and diversity strategies at USC Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, and Bryan F. Gaines, co-chair and project specialist for Advocates for African American Elders and assistant director of the Hartford Center of Excellence in Geriatric Social Work at the USC Roybal Institute.

The study was supported by a $28,500 grant from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50-AG05142) and two grants totaling $19,400 from the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1 TR001350).