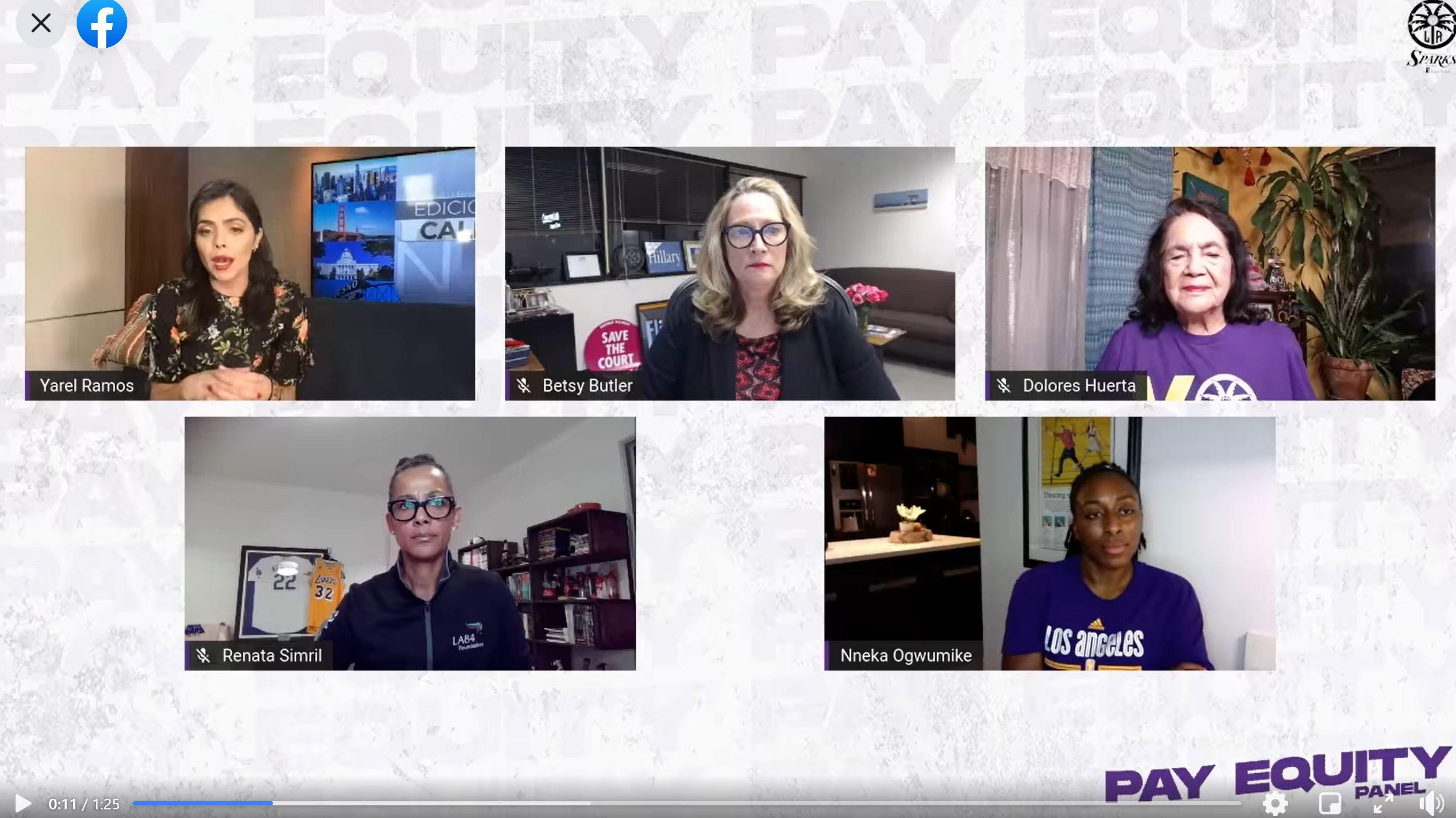

The Los Angeles Sparks recently hosted a conversation about pay equity. All-Star forward and WNBPA president Nneka Ogwumike, was featured in the panel along with National Farmworkers Association co-founder Dolores Huerta, LA84 Foundation President and CEO Renata Simril, and former California State Assemblymember Betsy Butler.

Although there has been an amount of progress, women get paid 89 cents to every dollar a man earns doing the same job. The amount is less if the woman is a minority.

Ogwumike discussed the new collective bargaining agreement for the WNBA, it increased player’s pay by 53 percent and offers full maternity benefits.

“It was clear to us that the changes that we made for working moms were not just obvious changes that needed to be made, but also changes that we didn’t realize haven’t been enacted in what we would consider more traditional jobs,” Ogwumike said.

Along with getting less pay than men, women hold very few leadership roles in different industries. For Simril, play equity equals pay equity. Playing a sport can give young girls the leadership skills that can help them advocate for themselves in professional settings. However, opportunities to compete may not be obtainable for working-class and impoverished families.

“The fact that it’s households earning below $25,000 a year have the highest level of lack of participation for young kids across the board, but certainly you see a widening gap from a gender perspective,” Simril said. “One in four girls don’t play sports in L.A. County.”

California can be a model of pay equity to other states because of its $13 per hour minimum wage and having an employment commission that protects women from discrimination, according to Huerta. She also applauded Ogwumike for being a professional female athlete.

“You are such a great symbol for young women,” Huerta said to Ogwumike. “It makes everybody so proud that you are there.”

Title IX, a law that ensures that schools provide sports teams for girls, became law in 1972. However, some school districts still fail to enforce it. Being the executive director of the California Women’s Law Center, Butler fights against the school districts to provide athletic programs for girls.

“The bottom line is when girls play in sports, they’re more likely to graduate from high school … go to college, they’re going to have stronger careers, get paid more,” Butler said. “Discrimination exists in the hiring and promotion practices, company cultures; historic systems of oppression make it difficult for women to invest in their educational and career opportunities.”

When asked about her experience of being a female in sports, Ogwumike noted how her generation takes for granted having an American professional basketball league for women. Going from having sellout crowds at Stanford to having a less populous crowd during Sparks games was an adjustment.

What empowered Ogwumike was an ability to be involved in the decisions that the WNBA makes.

“For me to be able to speak on panels like this with the likes of women who are leading experts in their fields and to contribute and use that in my own leadership qualities on both as a teammate and as the president,” Ogwumike said. “I feel as though that it’s my responsibility.”