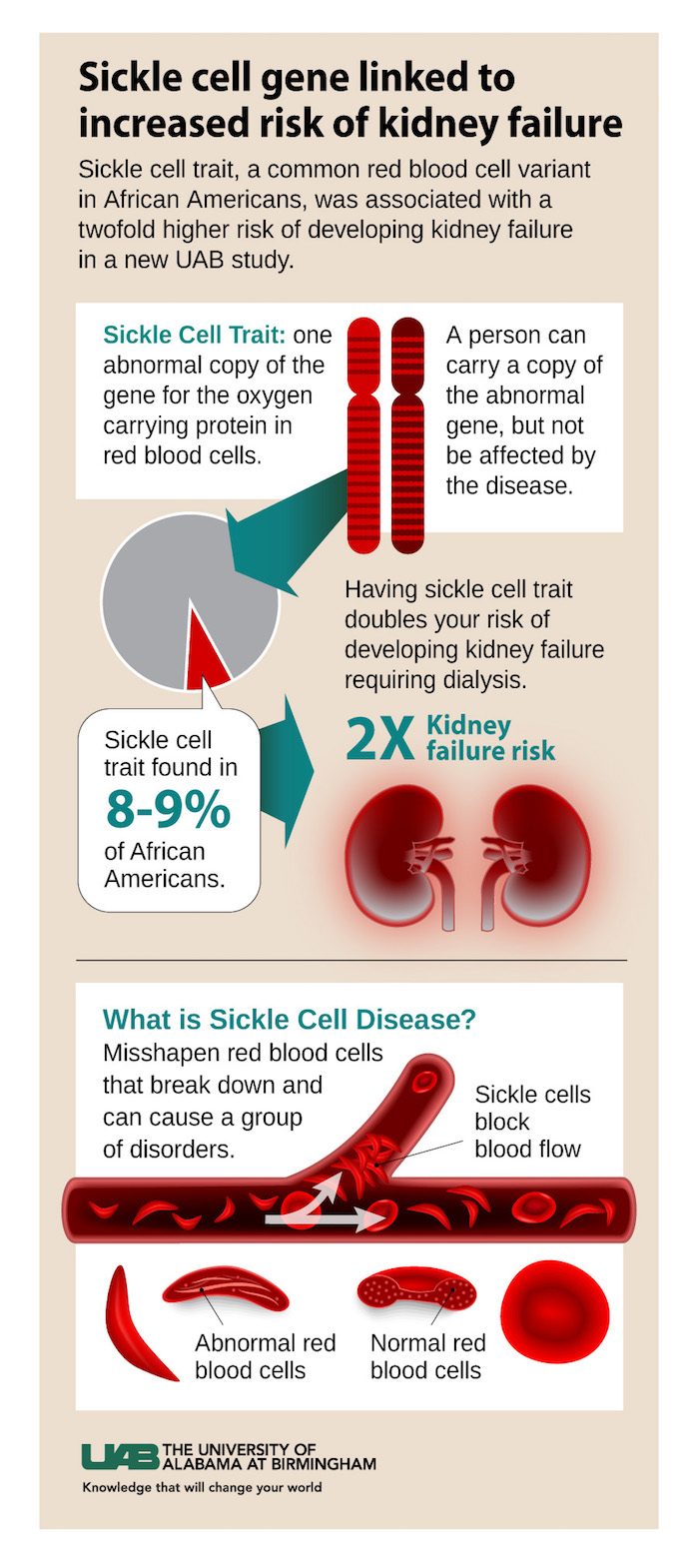

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – A person born with one abnormal copy of the gene for the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells, known as sickle cell trait, does not have sickle cell disease but is two times more likely to develop kidney failure requiring dialysis, according to a new study from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke cohort.

The REGARDS study findings, which appear in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, may have important public policy implications for genetic counseling for individuals with sickle cell trait.

Sickle cell trait and hemoglobin C are hemoglobin variants that are common in blacks. These variants are thought to have persisted throughout evolution due to their protective effects against malaria. Affected individuals do not have a disease: They carry only one copy of a hemoglobin gene variant, and unlike individuals with two copies of the variant, they do not experience symptoms. Prior evidence suggested that the variants may play a role in chronic kidney disease in blacks. However, the association of these hemoglobin traits to progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis was unknown.

A team led by Marguerite Irvin, Ph.D., assistant professor in the UAB School of Public Health Department of Epidemiology, and Rakhi Naik, M.D., assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, investigated these associations by using data from REGARDS, a large population-based study.

“REGARDS had a general-population-based sample of African-American participants large enough to determine the relationship of SCT with kidney failure, an outcome difficult to assess using other existing cohort studies,” Irvin said. “This study suggests it may be clinically useful to screen for SCT in families with a history of sickle cell disease to monitor more carefully for chronic kidney disease and its progression to end-stage renal disease.”

The researchers evaluated 9,909 blacks, of whom 739 had SCT and 243 had hemoglobin C trait.

Among the findings:

Kidney failure requiring dialysis developed in 40 of 739 (5.4 percent) individuals with SCT, six of 243 (2.5 percent) individuals with hemoglobin C trait and 234 of 8,927 (2.6 percent) non-carriers during the follow-up period.

The incidence rate for kidney failure was 8.5 per 1,000 person-years for participants with SCT and 4.0 per 1,000 person-years for non-carriers.

Compared with individuals without SCT, individuals with SCT had a twofold increased risk of developing kidney failure.

SCT conferred a similar degree of risk as APOL1 gene variants, which are the most widely recognized genetic contributors to kidney disease in blacks.

Hemoglobin C trait did not associate with kidney disease or kidney failure.

The investigators noted that SCT is currently identified at birth in the United States via the Newborn Screening Program.

“Although you cannot change the genes you are born with, doctors can use this information to start screening for kidney disease earlier and to aggressively treat any other risk factors you may have, such as diabetes or high blood pressure,” Naik said. “We still need more studies to determine if there are other treatments that can be used to slow the progression of kidney disease specifically in individuals with sickle cell trait.”

Study co-authors include Suzanne Judd, Ph.D., Orlando Gutiérrez, M.D., Neil Zakai, M.D., Vimal Derebail, M.D., Carmen Peralta, M.D., Michael Lewis, M.D., Degui Zhi, Ph.D., Donna Arnett, Ph.D., William McClellan, M.D., James Wilson, M.D., Alexander Reiner, M.D., Jeffrey Kopp, M.D., Cheryl Winkler, Ph.D., and Mary Cushman, M.D.

This article was originally published by University of Alabama at Birmingham News. Read more stories at www.uab.edu/news