The shooter rapidly fires through the front doors of an elementary school with an assault rifle and blasts his way down the hallway. Screaming children are running for their lives or frozen in fear. Teachers quickly try to decide: barricade the doors, or make a run for it with their students?

Police officers arrive with guns drawn, working their way through the school. Finally they confront the shooter and end the threat.

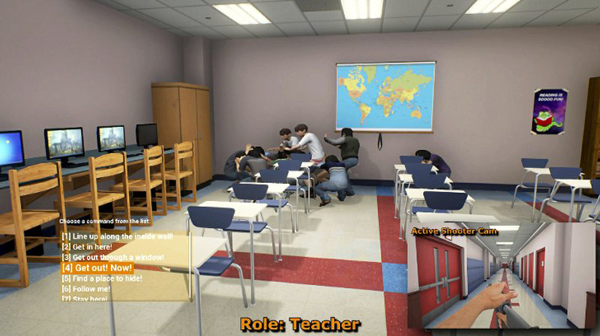

Using cutting-edge video game technology and animation, the U.S. Army and Homeland Security Department have developed a computer-based simulator that can train everyone from teachers to first responders on how to react to an active shooter scenario. The training center is housed at the University of Central Florida in Orlando and offers numerous role-playing opportunities that can be used to train anyone in the world with a computer.

“With teachers, they did not self-select into a role where they expect to have bullets flying near them. Unfortunately, it’s becoming a reality,” said Tamara Griffith, a chief engineer for the project. “We want to teach teachers how to respond as first responders.”

The $5.6 million program – known as the Enhanced Dynamic Geo-Social Environment, or EDGE – is similar to those used by the Army to train soldiers in combat tactics and scenarios using a virtual environment.

Originally designed for police and fire agencies, the civilian version is now being expanded to schools to allow teachers and other school personnel to train for active shooters alongside first responders. Homeland Security officials say the schools version should be ready for launch by spring.

Each character has numerous options, including someone playing the bad guy, said project manager Bob Walker. For example, each teacher has seven options on how to keep students safe, and some of the students in the program might not respond or be too afraid to react. So that becomes another problem to be solved.

“Once you hear the children, the screaming, it makes it very, very real,” Walker said.

The program can have the shooter be either an adult or a child.

“We have to worry about both children and adults being suspects,” he said.

The program’s designers listened to real dispatch tapes to understand the confusion and chaos that goes along with such frightening situations, Griffith said. They also talked to the mother of a child killed in the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, who walked them through everything that happened that tragic day.

“It gives you chills when you think about what’s happening on those tapes,” Griffith said. “It tore us apart to listen to her and what she went through.”

But it all serves one main goal: to train educators to save lives when an armed attacker bursts through a school door.

Another EDGE program, which was launched in June, has an active-shooter scenario involving a 26-story hotel that includes numerous possible environments for first responder training: a conference center, a restaurant, or office spaces. As many as 60 people can train on the program at once and can be located anywhere.

“It’s important that this provides agencies like fire and law enforcement an opportunity to train together,” said Milt Nenneman, Homeland Security Science and Technology First Responder Group program manager in a recent Justice Department article. “Very seldom do they have the opportunity to train together in real-life, and it is hard to get those agencies time away from their regular duties.”

School safety advocates say safety training gets pushed to the back burner until a tragedy happens. Amanda Klinger, director of operations for nonprofit Educators School Safety Network, said this new program could help change that.

“I hope that people will sort of see this simulation as a really cool and engaging way,” she said, “to think about school safety.”