This May 1, 1992 file photo shows Rodney King making a statement at a Los Angeles news conference. King, the black motorist whose 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles police officers was the touchstone for one of the most destructive race riots in the nation’s history, has died, his publicist said Sunday, June 17, 2012. He was 47. (AP Photo/David Longstreath, file)

.jpg)

This March 31, 1991 image made from video shot by George Holliday shows police officers beating a man, later identified as Rodney King. King, the black motorist whose 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles police officers was the touchstone for one of the most destructive race riots in the nation’s history, has died, his publicist said Sunday, June 17, 2012. He was 47. (AP Photo/Courtesy of KTLA Los Angeles, George Holliday)

This file photo of Rodney King was taken three days after his videotaped beating in Los Angeles on March 6, 1991. King, the black motorist whose 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles police officers was the touchstone for one of the most destructive race riots in the nation’s history, has died, his publicist said Sunday, June 17, 2012. He was 47. (AP Photo/Pool, File)

.jpg)

This July 20, 1993 file photo shows Rodney King speaking during an appearance on KFI-AM radio’s “Bill Handel and Mark Whitlock” show in Los Angeles. King, the black motorist whose 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles police officers was the touchstone for one of the most destructive race riots in the nation’s history, has died, his publicist said Sunday, June 17, 2012. He was 47. (AP Photo/Nick Ut, file)

The swimming pool at Rodney King’s home is seen in Rialto, Calif., Sunday, June 17, 2012. King, the black motorist whose 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles police officers was the touchstone for one of the most destructive race riots in U.S. history, died Sunday. He was 47. King’s fiancee called police to report that she found him at the bottom of the swimming pool at their home in Rialto, Calif,, police Lt. Dean Hardin said. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rodney King, key figure in LA riots, dies at 47

By CHRISTOPHER WEBER | Associated Press

Rodney King, the black motorist whose 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles police officers was the touchstone for one of the most destructive race riots in the nation’s history, was found at the bottom of his swimming pool early Sunday and later pronounced dead. He was 47.

King’s fiancée called 911 at 5:25 a.m. to report that she found him in the pool at their home in Rialto, Calif., police Lt. Dean Hardin said.

Officers arrived to find King in the deep end of the pool and pulled him out.

King was unresponsive, and officers began CPR until paramedics arrived. King was taken to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 6:11 a.m., police said.

Police Capt. Randy De Anda said King had been by the pool throughout the early morning and had been talking to his fiancee, who was inside the home at the time. A statement from police said the preliminary investigation indicates a drowning, with no signs of foul play.

Investigators will await autopsy results to determine whether drugs or alcohol were involved, but De Anda said there were no alcoholic beverages or paraphernalia found near the pool.

Authorities didn’t identify the fiancée. King earlier said he was engaged to Cynthia Kelley, one of the jurors in the civil rights case that gave King $3.8 million in damages.

The 1992 riots, which were set off by the acquittals of the officers who beat King, lasted three days and left 55 people dead, more than 2,000 injured and swaths of Los Angeles on fire. At the height of the violence, King pleaded on television: “Can we all get along?”

King, a 25-year-old on parole from a robbery conviction, was stopped for speeding on a darkened street on March 3, 1991. He was on parole and had been drinking — he later said that led him to try to evade police.

Four Los Angeles police officers hit him more than 50 times with their batons, kicked him and shot him with stun guns.

A man who had quietly stepped outside his home to observe the commotion videotaped most of it and turned a copy over to a TV station. It was played over and over for the following year, inflaming racial tensions across the country.

It seemed that the videotape would be the key evidence to a guilty verdict against the officers, whose trial was moved to the predominantly white suburb of Simi Valley, Calif. Instead, on April 29, 1992, a jury with no black members acquitted three of the officers on state charges in the beating; a mistrial was declared for a fourth.

Violence erupted immediately, starting in South Los Angeles.

Police, seemingly caught off-guard, were quickly outnumbered by rioters and retreated. As the uprising spread to the city’s Koreatown area, shop owners armed themselves and engaged in running gun battles with looters.

During the riots, a white truck driver named Reginald Denny was pulled by several black men from his cab and beaten almost to death. He required surgery to repair his shattered skull, reset his jaw and put one eye back into its socket.

King himself, in his recently published memoir, “The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption,” said FBI agents warned him a riot was expected if the officers were acquitted, and urged him to keep a low profile so as not to inflame passions.

The four officers who beat King — Stacey Koon, Theodore Briseno, Timothy Wind and Laurence Powell — were indicted in the summer of 1992 on federal civil rights charges. Koon and Powell were convicted and sentenced to two years in prison, and King was awarded $3.8 million in damages.

The police chief, Daryl Gates, who had been hailed as an innovator in the national law enforcement community, came under intense criticism from city officials who said officers were slow to respond to the riots, and resigned under pressure soon after. Gates died of cancer in 2010.

In the two decades after he became the central figure in the riots, King was arrested several times, mostly for alcohol-related crimes, the last in Riverside Calif., last July. He later became a record company executive and a reality TV star, appearing on shows such as “Celebrity Rehab.”

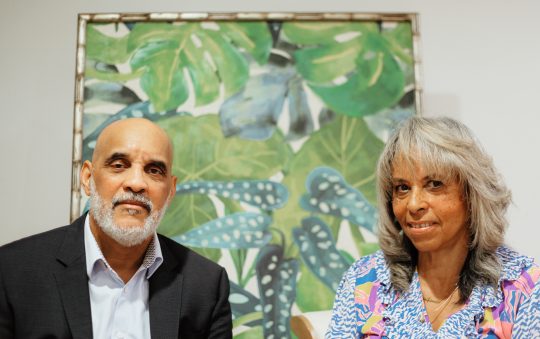

In an interview earlier this year with The Associated Press, King said he was a happy man.

“America’s been good to me after I paid the price and stayed alive through it all,” he says. “This part of my life is the easy part now.”

Rev. Al Sharpton said in a statement that King was a symbol of the civil and anti-police brutality movement.

“Through all that he had gone through with his beating and his personal demons he was never one to not call for reconciliation and for people to overcome and forgive,” Sharpton wrote. “History will record that it was Rodney King’s beating and his actions that made America deal with the excessive misconduct of law enforcement.”

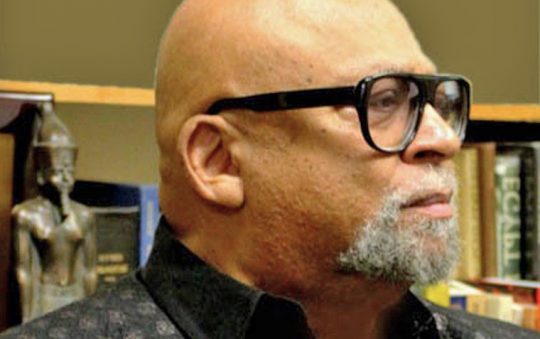

Attorney Harland Braun, who represented one of the police officers, Ted Briseno, in the federal trial, said King’s name would always be a part of Los Angeles history.

“I always saw him as a sad figure swept up into something bigger than he was,” Braun said. “He wasn’t a hero or a villain. He was probably just a nice person.”

King’s case never would have become such a symbol without the video, he said.

“If there hadn’t been a video there would have never been a case. In those days, you might have claimed excessive force but there would have been no way to prove it.”

The San Bernardino County coroner will perform an autopsy on King within 48 hours.