This too is in remembrance, reflection and uncompromising reaffirmation. There is so much damage done to memory and mission in our lives and to our sense of self by large and small concessions to the constant call to let go and move on regardless of what is lost or left behind. We sacrifice so much in our rush to forget, stay in style or keep in harmony with the official writers and rulers of society. However, whatever we are and will become, we must give appropriate attention to our history, in spite of all the counsel from outside to forget the past, worship the present and forfeit our future for things embraced and enjoyed now.

Thus, on this anniversary month of the Million Man March/Day of Absence, October 16, 1995, we must be careful not to forget or diminish the impact and importance of this great event of the 20th century. It was not just the brilliance and timeliness of the idea by Min. Louis Farrakhan, who rightly read the urgency of the historical moment; nor the size of the MMM/DOA in D.C., two million men and women, rivaled only by President Barack Obama’s inauguration. It was also the exemplary organizing work that went into it by the Nation of Islam and the local organizing committees which activists built in over 318 cities; and the important role of the National Executive Council and National Organizing Committee formed on the principle of operational unity and to reaffirm the openness to women, especially in the Day of Absence activities, but also in the March itself. And finally, the significance of this moment and Movement in history, was its impact on the men, as well as the women and community, their heightened political consciousness and practice, and their active recommitment to strengthen our families and our people in positive and concrete ways.

However, the critical reading and rightful remembering of history is not automatic or easy, but requires steadfast resistance to the established order’s version of things. Indeed, from the beginning, the established order and its allies attempted to discredit the MMM/DOA and deny its numbers and its clear and cogent emphasis on social policy and social change. This dual emphasis is obvious in the Million Man March/Day of Absence: Mission Statement, written by this author, and which evolved as a consensus document, an earnest effort by the National Executive Council to build on common ground and bring forth some of our best thinking and deepest commitments in our life and struggle as persons and a people. The statement of mission offers us a way to keep alive the spirit and social aims of the Movement by studying the document and struggling to bring the aspirations enclosed to fruition and fulfillment.

The Mission Statement begins with a conscious recognition of the critical juncture of history at which we are living and the challenge it poses for us, i.e., issues of racism, classism, sexism; deteriorating social and environmental conditions; the country’s and governments’ “dangerous and repressive turn to the right” and their “producing policies with negative impact on people of color, the poor and the vulnerable; and the urgent need for audacious, transformative and progressive leadership and activism. Especially stressed was our commitment to “reaffirming the best values of our social justice tradition which require respect for the dignity and rights of the human person, economic justice, meaningful political participation, shared power, cultural integrity, mutual respect for all people and uncompromising resistance to social forces and structures which deny or limit these.” We had posed and pursued the MMM/DOA as a challenge to both ourselves and society, stating our “understand(ing) that the challenge to ourselves is the greatest challenge. For it is only by making demands on ourselves that we can make successful demands on society.”

Moreover, “we declare(d) our commitment to assume a new and expanded responsibility in the struggle to build and sustain a free and empowered community, a just society and a better world.” And we noted that “we are aware that we make this commitment in an era in which this is needed as never before and in which we cannot morally choose otherwise.”

The March’s stress on the Black man’s standing up was placed for two basic reasons. First, “some of the most acute problems facing the Black community within are those posed by Black males who have not stood up.” Secondly, “unless and until Black men stand up, Black men and women can’t stand together and accomplish the awesome tasks before us.” We had challenged the corporations and government to act responsibly. For we argued, central to our practice of responsibility is not only holding ourselves responsible, but also “holding responsible those in power who have oppressed and wronged us.” We criticized the U.S. government for participating in one of the greatest holocausts of human history, the Holocaust of African enslavement” and demanded reparations. Moreover, we called for an end to its criminalizing of a whole people, policies destructive to Black leadership and the Black community, unjust imprisonment, war and war-mongering, degradation of the environment and reversal of hard-won gains.

And we called for “an economic bill of rights, universal, full and affordable health care, affordable housing, rebuilding the cities, protection of the environment, and a halt to privatization of public wealth and space.” We also called for honoring the just claims of Native peoples and an international policy of equal treatment of African and other Third World refugees (and immigrants), justice and peace, as well as cancellation of debt and self-determination for all peoples. And we called on the government “to increase and expand efforts to eliminate race, class and gender discrimination and stop pandering to White fears and White supremacy hatreds and illusions.” For corporations, the call to responsibility included the demand to respect the dignity and interests of the workers and the integrity of the environment; to share and reinvest profits back into the community; and to provide business opportunities and development programs in order to halt and reverse urban decay.

We ended the Mission Statement with a challenge and call to ourselves to sustain and institutionalize this moment and Movement. This was to include a new and independent political practice and economic initiative; a massive ongoing voter registration process, and rebuilding the Movement and an effective Black united front. It also called for strengthening of family and community “thru quality male/female relations based on the principles of equality, complementarity, mutual respect and shared responsibility in love, life, and struggle, (and thru) . . . loving and responsible parenthood.” It also included a call for continuing resistance to police abuse, government suppression, violations of civil and human rights and the industrialization of prisons”; support of political prisoners and prisoners’ rights; struggle against drugs and communal violence; support for independent schools and public education; building independent media and reshaping established-order media; increasing organizational involvement; solidarity with other Africans; alliance with other peoples of color; challenging our religious institutions to be more socially conscious and involved; and practicing the Nguzo Saba, The Seven Principles.

We ended the Mission Statement saying, “through this historic work and struggle we strive to always know and introduce ourselves to history and humanity as a people who are spiritually and ethically grounded; who speak truth, do justice; respect our ancestors and elders; cherish, support and challenge our children; care for the vulnerable; relate rightfully to the environment; struggle for what is right and resist what is wrong; honor our past, willingly engage our present and self-consciously plan for and welcome our future.”

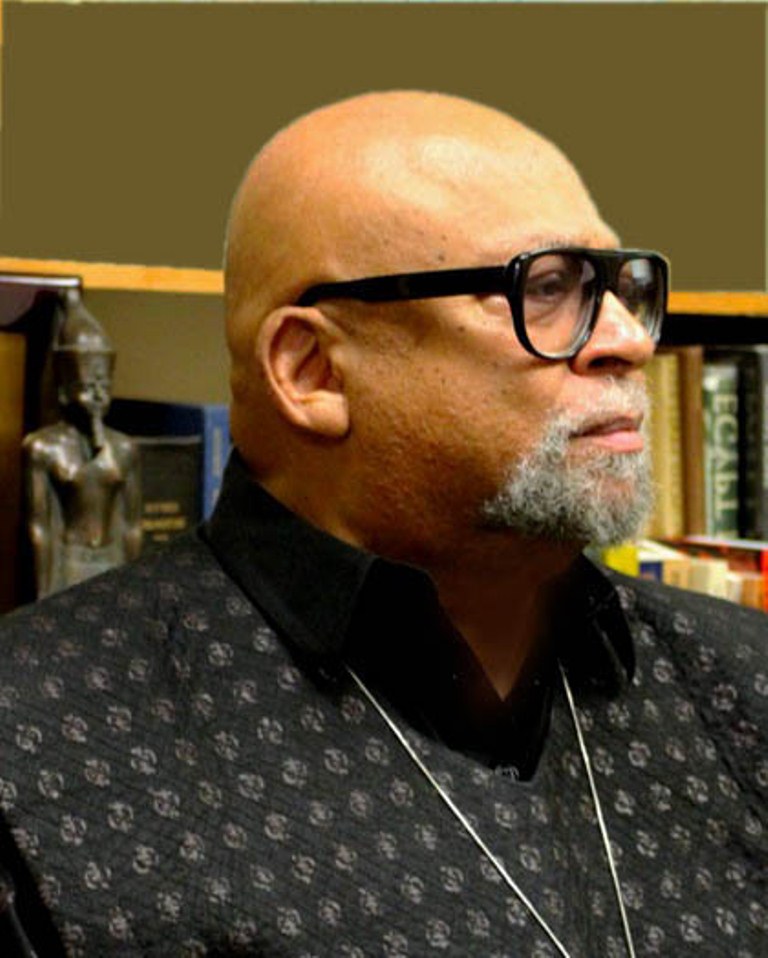

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite. org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.