In the process of review and reflection for the 50th anniversary celebration of our organization Us, our philosophy Kawaida, and our core values, the Nguzo Saba (The Seven Principles), I retrieved a classic article by Dr. Vincent Harding, one of the most thoughtful activist theologians of our times (May the good he left last forever.). And on this the 53rd anniversary, as part of our remembrance, reflection and recommitment, I would like to share again what I wrote. His article is called “The Religion of Black Power” and was written in 1968. In this article, he engages my thought in ways few writers in the early days and even less in later years have done. He draws exclusively from The Quotable Karenga and places my thought Kawaida, without naming it, in comparative conversation with Kwame Toure, Nathan Wright and others in the vanguard of the Black Power Movement and with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and him, from the Civil Rights Movement and Christian position.

Harding places us, our leadership, philosophy and organization in the vanguard of the Movement, characterizing me as “one of the best trained and most thoughtful of the Black Power leaders.” And he asserts that our organization Us “has so far articulated the most clearly structured and self-conscious religious manifesto of all the Black Power groups.” Moreover, he continues, “It is representative of much of the Movement’s concerns both in its rather humanistic, secular (in the most religious sense of that word) orientation and in its obvious reaction to the Black Christian churches.”

Now, in spite of his laudatory assessment of me and Us, Harding has rightfully placed us in the vanguard of the Movement, not mistakenly called us the vanguard of the Movement. For no one group could accurately and honestly claim such a status at the expense and dismissal of all the groups fighting on the frontline, i.e., in the vanguard of the Movement. Certainly, we saw and see ourselves as a vanguard organization and in the vanguard of the Movement, second to none in leadership, philosophy, organization, paramilitary capacity and readiness, and revolutionary commitment in thought and practice.

And if the attitude of the state toward a group is any indication of the radical nature of its thought and practice, it bears noting that we, Us, were on every FBI list of radical and revolutionary groups any other group was on, that we were victims of the Cointelpro program and were attacked, imprisoned on trumped-up charges, forced underground and in exile, and the target of a propaganda campaign of vicious misinformation, disinformation and discrediting still in process. Here it is important to note that what FBI Chief Hoover feared was not any one group, but rather by his own words in the Cointepro document, he feared and worked to “prevent the coalition of militant black nationalist groups. (For) In unity there is strength.” What he feared then was our active unity, our becoming a united self-conscious social force for liberation and radical and revolutionary transformation of society.

When Harding says our “manifesto” or publically expressed philosophy is religious, he misreads it. For it is not religious, but essentially ethical, focused on values, concrete conditions of life and the moral requirements for a good life and for waging the liberation struggle. Kawaida, as an ongoing synthesis of the best of African thought and practice in constant exchange with the world is a cultural and social change philosophy, ethical at its core. And the Nguzo Saba (The Seven Principles) are essentially ethical in their content and intention to offer culturally-grounded and rightful ways to reflect on and cultivate ourselves and our relations, understand and carry out our obligations and build the good and caring families and communities we all want and deserve to live in. In a word, they offer a moral and cultural mapping and motivation to discover and pursue paths leading to our becoming and being the best of what it means to be African and human in the fullest sense.

And clearly, by extension, these principles are also ways we understand and engage society and the world in our efforts to create and sustain the just and good society and world we all, again, want and deserve. Indeed, he, himself, designates our philosophy as “humanistic” and “secular”. What he is responding to is the depth of our commitment to our people and the struggle which resembles religious faith. Certainly, our willingness to be martyred in righteous resistance, like Malcolm, takes on tones familiar in religious discourse. But it is also present in revolutionary speech and writing. Thus, we said, “We must believe in our cause and be willing to die for it. And we should stop (simply) reading other peoples’ literature and write our own and stop pretending revolution and make it.”

Furthermore, Harding cites the quote of mine, “The fact that we are Black is our ultimate reality.” It is a quote Dr. James Cone, dean of Black liberation theology, cites as a point of departure for Black liberation theology and one which the poet laureate Gwen Brooks uses to introduce one of her poems. Harding recognizes that “There is a certain soundness in this view,” that it is a welcomed counter to escapist views and a reaffirmation of our own humanity. But he is rightfully concerned that it does not lead to isolation or disdain of “the goal of universal community” which he posits as essential.

Still, he reaffirms the good in my contention that “Our purpose in life should be to leave the Black community more beautiful than we inherited it.” Moreover, he points out that I stated that “We’re not for isolation, but interdependence—but we can’t become interdependent unless we have something to offer”—in a word, until we are independent, free and have the capacity or power to choose, build and exchange in mutual respect and mutual benefit. What we need, then, is power over our destiny and daily lives, and for us, this becomes a moral imperative.

Now, Harding is also concerned about Kwame Toure’s and my commitment to the right and responsibility of self-defense. He notes that Toure, “reaffirms the right of Black men everywhere to defend themselves when threatened”. And he is aware of my statement that “Black Power. . . is the means to obtain three things self-determination, self-respect and self-defense.” Thus, he notes that I write “If we fight we might be killed, But it is better to die a man than to live like a slave.” In the same vein, I also wrote, “If we fight we might be killed. But if we give in, we degrade ourselves and therefore cannot live with ourselves.”

Dr. Harding notes that Dr. Nathan Wright, chairman of the National Conference on Black Power and I, a vice-chair and major theorist of the Conference, agree that God is “A God of power,” that this has theological and ethical implications for our understanding of ourselves as images of God and our need for power to act in divinely-willed, creative and good ways. Indeed, we argue it is immoral to disempower a person or a people and to deny them the freedom and capacity to live lives of dignity, decency and continued development which they deserve as bearers of dignity and divinity. And thus, it is not only an oppressed people’s human right, but also their moral responsibility to engage in righteous and relentless struggle to free themselves and be themselves in good, expansive and life-enhancing ways. But again, Harding, like all our moral teachers, rightly cautions us to be measured and moral in our quest and constant striving.

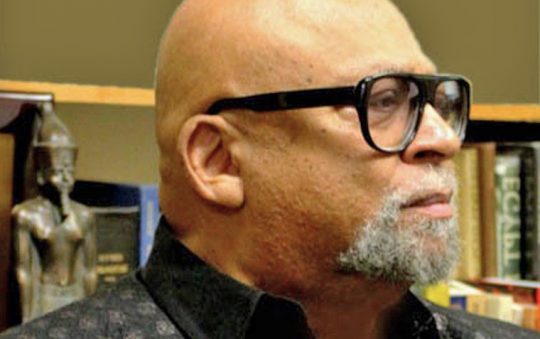

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.