Fourteen years ago, the Southern Poverty Law Center sent the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice a list of 74 cold cases involving African Americans allegedly murdered in racially motivated circumstances by White people between 1952 and 1968.

Most of the crimes took place in Mississippi, which contained nearly half of the 74 cases. Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee all made up the rest.

All went cold, and the victims’ families never received justice.

Today, a new path to justice has opened to crack these cold cases.

On Friday, June 11, President Joe Biden announced the first set of nominees for the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board.

The panel would have the power to declassify government files and subpoena new testimony that could reopen cases and reveal publicly why many racially motivated lynchings and killings of Black people were never adequately investigated.

“The White House hopes that the Senate moves quickly to [confirm] these nominees,” an administration official told the National Newspaper Publishers Association.

“The Board was established with nearly unanimous bipartisan support in 2019,” the official noted.

President Biden’s nominees are:

- Clayborne Carson has devoted most of his professional life to the study of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the movements Dr. King inspired. Since receiving his doctorate from UCLA in 1975, Dr. Carson has taught at Stanford University as the Martin Luther King, Jr., Centennial Professor of History (Emeritus).

- Gabrielle M. Dudley, an Instruction Archivist at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University. In this role, she partners with faculty and other instructors to develop courses and archives research assignments for undergraduate and graduate students.

- Hank Klibanoff, a veteran journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize in History in 2007 for a book he co-wrote about the news coverage of the civil rights struggle in the South. Klibanoff is the creator and host of Buried Truths, a narrative history podcast produced by WABE (NPR) in Atlanta.

- Margaret Burnham has served as a state court judge (appointed by Governor Michael Dukakis, 1977), civil rights lawyer, and human rights commissioner. A graduate of Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi, and the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Burnham has been on the Northeastern University faculty since 2002. She was named to the 2016 class of Andrew Carnegie Fellows, an honor recognizing a select group of scholars for their significant work in the social sciences and humanities.

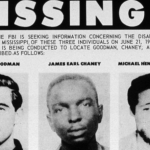

The panel could consider cases like the three civil rights workers in Mississippi – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner – killed by the Ku Klux Klan in June 1964.

Two months later, the activists’ bodies were riddled with bullets, burned, and buried in a dam in Neshoba County.

The “Mississippi Burning” case has largely gone unsolved and primarily unpunished.

In 2005, Edgar Ray Killen was convicted of three counts of manslaughter and sentenced to 60 years in prison, but authorities closed the case and put an end to hopes of prosecuting others involved.

In Lowndes County, Alabama, there is the case of 18-year-old Rogers Hamilton.

On a brisk night in October 1957, two White men arrived at Rogers’ home, summoned him outside, and put him in a truck.

His mother, Beatrice Hamilton, trailed the truck on a dusty road and watched in horror as they pulled Rogers out of the vehicle and shot him in the head.

When she notified the sheriff, he told her she didn’t see what she “thought she saw” and closed the case.

“No one cared, except his extended family, now scattered from Chicago to New York,” John Fleming, an editor at the Center for Sustainable Journalism, wrote in a 2011 column. “The case remains open, though the reality is that this case will never be prosecuted,” Fleming decided.

“Though the family wants justice, even if it means getting the local district attorney to indict a dead deputy, what’s equally important to them is the fact that the story of a long-dead [man] in faraway Alabama has finally been told.”