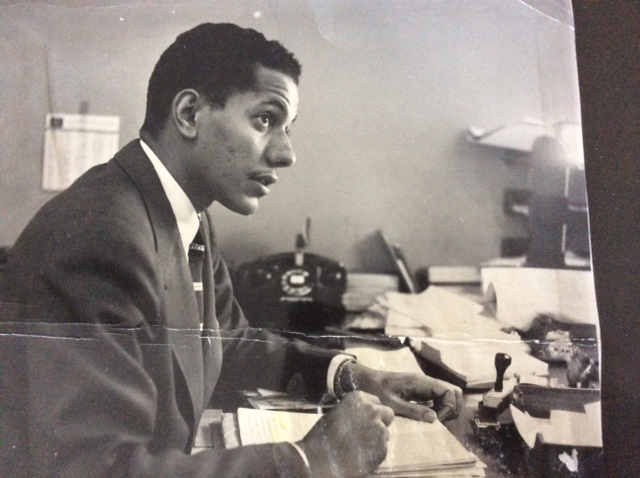

Born in Dallas Texas in 1926, Louie Robinson defied the odds of a time when America denied the existence of Black excellence, let alone the tools with which a Black writer could emerge to chronicle such things. Robinson not only showcased some of the nation’s most famous symbols of Black achievement, he exposed their humanity in such a way that readers might see themselves in the stars. Sidney Poitier was first interviewed by Robinson in 1955, before the Bahamian born actor was well-known.

But he had been cast in the film Blackboard Jungle by a major studio, which made him newsworthy to Black readers.

“We were to meet at MGM and trying to figure out how we would recognize each other,” Robinson said in a recent interview, “ then it hit us: if you’re there, you are one Black man. I will be the other one.

Poitier describes the passing of the writer who became a friend and collaborator as a major loss.

“Never in my life have I known a better man. His life was an experience that will leave behind memories of major importance. In his life from which many humane experiences have arisen to the benefit of so many of his fellow human beings, he has always stood strong and he has always reached out to those in need”

When he joined Johnson Publishing Company in the late 50’s, the timing was just right for a self-taught newspaper man looking to open the world like a book. Black stars were emerging on stage and screen, in sports, politics and business – and demanding equal access and attention. After Robinson was promoted to West Coast Editor of Ebony Magazine in 1960, his stories graced the covers for the next 30 years. He fulfilled a passion and worked to fill a void he first noticed as a child growing up in Mineral Wells Texas. In his yet unpublished memoirs, Robinson writes about what was missing at the time:

“I listened to the radio, read newspapers, witnessed life as presented in the movies, and in time studied American civics, not yet quite realizing that these were devoted to the White version of America, and that the Blacks I did not hear or see or read about in all this were the Blacks whose existence most of America did not truly wish to recognize.”

Known for his engaging writing style, integrity and a passion for facts instead of gossip, ROBINSON won the respect of those he covered over the years,. His articles profiled the struggles and triumphs related to making it big in a system intent on keeping Black people small. Sammy Davis Jr. was a member of the storied Rat Pack with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop, but while he performed to packed houses at Las Vegas casinos, the entertainer’s Caucasian valet still had to place his bets for him. No Blacks were allowed at the gaming tables.

Many of the people Robinson wrote about became lifelong friends, including Davis, singer Nancy Wilson, tennis champion Arthur Ashe, comedians Nipsey Russell and Bill Cosby, baseball pioneer Curt Flood and, most notably, actor Sidney Poitier with whom he helped organize two books nearly 30 years apart: This Life (1980), and Life Beyond Measure (2008) . Robinson also wrote the first book on Arthur Ashe, Arthur Ashe: Tennis Champion (1970) and was chosen by Maria Cole to co-author her late husband’s life story in Nat King Cole, an Intimate Biography (1971),

Robinson also explored the complicated relationship between White audiences and the Black superstars they at once applauded and sometimes derided. When Elvis Presley topped the charts with his fusion of White hillbilly music and Black rhythm and blues, it was Robinson who tracked him down for Jet Magazine in 1957 to ask about racist comments being attributed to him. Presley denied ever saying, “The only thing Negroes can do for me is buy my records and shine my shoes.” telling Robinson he would never say such a thing and that people who know him knew he would never say it. Robinson confirmed this with several Black sources and his story knocked down the rumor.

If Robinson was ever star-struck, it never showed. He didn’t marvel at celebrity, only at his own good fortune to be able to do what he loved: writing.

Louie Robinson passed away at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago on October 2nd, 2 days before his 89th birthday, after a long battle with heart failure. He is survived by his wife of 62 years, Mati Delores, a retired career counselor, 4 of their 6 children, Toni Frazer, Michael Robinson, Robin Robinson and Stacy Robinson-Hinkhouse, son-n-law Lou Hinkhouse, 10 grandchildren, 13 great-grandchildren and 5 great-great-grandchildren. A private memorial service is planned.

Contributions in honor of Louie Robinson are invited to the Southern Poverty Law Center, donate.splcenter.org. To acknowledge your support or contact the family, please use the email LouieRobinsonLegacy@gmail.com