Back in the early 1980s, I worked in the legal and aerospace industries where the work environments were predominantly White. I worked my way up to supervisory positions, honing my writing and speaking skills so much so that vendors whom I dealt with over the phone assumed I was White. You should have seen the looks on their faces when we met face to face.

So, I could relate to the segment in the PBS documentary, “Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story,” where White prospects would come seeking his services, only to reject him when they learned he was Black. When they would do so, he’d ask, “How much are you planning to spend on this project?” If they said $8,000, he’d wittily retort, “We don’t take on projects less than $10,000” as a way of asserting the prestige of his firm.

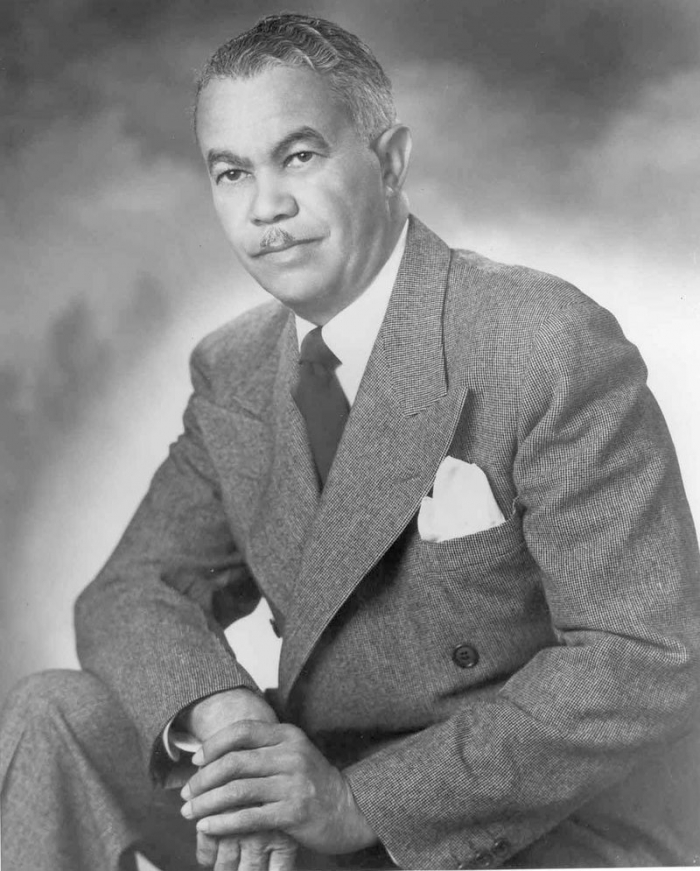

Pioneer Paul Revere Williams, born February 18, 1894 with an orphan background, followed his dream of becoming an architect and by the early 1920s was designing homes and commercial buildings in and around Los Angeles. He became the architect of choice among Hollywood’s elite including stars Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Lon Chaney and Barbara Stanwyck.

He and actor Danny Thomas became good friends. Williams gave Thomas his blueprint for the St. Jude Hospital that bears his name. At the time of his death on January 23, 1980, Williams had created some 2,500 buildings in the United States and around the globe.

Related Stories

Inglewood Football Seniors Commit to Colleges

Crenshaw Has Six-Game Winning Streak After Win Against Washington Prep

Always representing himself well-dressed, mild-mannered and professional, Williams easily fit into White circles, but despite all of his career successes and popularity, he was not always welcomed even in some of the buildings he had designed because he was Black.

Williams was the first Black architect to be admitted to the American Institute of Architects (AIA). One of his crown jewels is the design of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

In an essay titled “I Am A Negro” published in 1937 by American Magazine and reprinted in 1986 by Ebony Magazine, Williams wrote, “I came to realize that I was being condemned, not by a lack of ability, but by my color. I passed through successive stages of bewilderment, inarticulate protest, resentment, and, finally, reconciliation to the status of my race.

“Eventually, however, as I grew older and thought more clearly, I found in my condition an incentive to personal accomplishment, an inspiring challenge. Without having the wish to ‘show them,’ I developed a fierce desire to ‘show myself.’ I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, as an individual, deserved a place in the world.”

For Black History Month, please check your local PBS listings for “Hollywood’s Architect” to see how Paul R. Williams used talent, determination and even charm to defy the odds and create a celebrated body of work.

Larry Buford is the author of “Things Are Gettin’ Outta Hand” and “Book To The Future” (Amazon). Email: [email protected]