The National Park Service (NPS) is set to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Port Chicago explosion, a tragic event that claimed the lives of 202 Black sailors. The incident occurred on July 17, 1944, in Contra Costa County, when 4,606 tons of ammunition being loaded unto two U.S. Navy cargo ships detonated, instantly killing 320 men on site and injuring another 390 workers.

On July 20, the National Park Service (NPS) in collaboration with Friends of Port Chicago National Memorial band, the U.S. Army’s 834th Transportation Battalion, will host the commemoration at the Military Ocean Terminal Concord (MOTCO) in Concord.

According to organizers, the event provides an opportunity for friends, family, journalists, and others interested in the history of the disaster to honor the memory of the victims and shed light on the largest mutiny trial in U.S. naval history.

The Rev. Amos C. Brown, president of the San Francisco Branch of the NAACP, and the pastor of the Third Baptist Church of San Francisco, says he continues to seek justice for the men who died in the blast and survivors who later were accused of rebellion.

“It was nothing but another instance of forces in America being perpetrators of hate, harm, and hardship of Black folks,” Brown said of tragedy and the injustice that followed. These Black men who died in that blowup several miles from San Francisco should never be forgotten.”

Jake Sloan, an Oakland resident with extensive knowledge of San Francisco Bay shipyards that attracted many African American men from the South seeking employment during the World War II, attended the 75th commemoration of Port Chicago at MOTCO.

Sloan, the author of “Standing Tall: Willie Long vs. U.S. Government at Mare Island Naval Shipyard,” said standing on the grounds where the explosion occurred was a surreal feeling.

“It was quite an event. It was exciting in a way and sad in another way,” Sloan told California Black Media (CBM) of his experience at the monument site. “I actually walked through the site in addition to attending the ceremony. If you’re an African American, and if you know the story, you can almost feel it.”

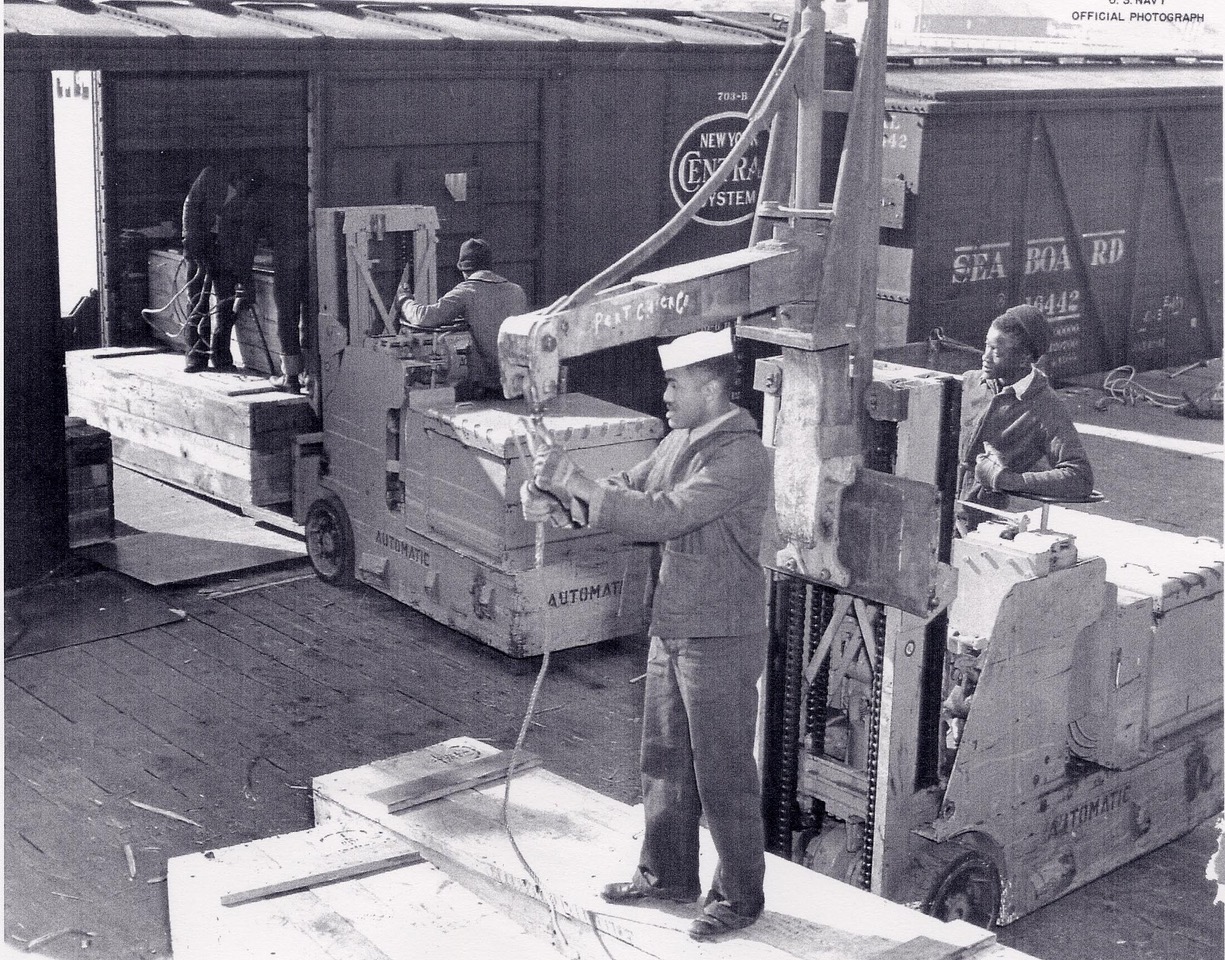

Located 35 miles northeast of San Francisco, the Port Chicago pier was built in 1942 and expanded within two years to accommodate space for the loading of naval cargo ships.

According to the Naval History and Heritage Command (NNHC), around 10:18 p.m., a “seismic shock wave” that started at Port Chicago shook the entire San Francisco Bay and “was felt as far away as Boulder City, Nevada. The explosion was so powerful that it decimated both ships, sent debris flying for miles over the Suisun Bay, and left a large crater in place of the pier.

Brown also said the African American sailors were unfairly blamed for the explosion, which was later determined to have been an accident likely caused by unsafe working conditions and lack of proper training.

What ensued after the explosion highlighted the racial disparities in the Navy’s policies at the time.

“In the aftermath, surviving sailors were ordered to resume the same dangerous tasks without any changes to safety protocols,” NPS described on its webpage dedicated to Port Chicago Naval Magazine, which was converted into a National Memorial Park.

“On Aug. 9, 1944, 258 African American sailors refused to work, leading to 50 being charged with mutiny.”

The men were dishonorably discharged for refusing to follow a racially motivated order to clear debris from the area and retrieve sailors’ appendages, many of them who were the survivors’ friends and fellow servicemembers. White officers were given hardship and time off following the accident.

U.S. Representatives John Garamendi (D-CA-08) and Mark DeSaulnier (D-CA-10) have been working to seek justice for victims and their families.

“The Port Chicago 50 were ordered to their deaths in the summer of 1944, nearly four years before President Truman signed the executive order formally banning racial segregation in the American military,” Garamendi said in 2023.

“Now, almost eight decades later and even after President Clinton’s 1999 pardon for Freddie Meeks, the families of the Port Chicago 50 convicted for mutinying against an order that should never have been given are still waiting for justice.”

The court hearings and trials were conducted at Treasure Island Naval Base in San Francisco and Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo.

In an Aug. 24, 1980 interview for the University of Californiahttps://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=https-3A__www.youtube.com_watch-3Fv-3DPz1tNVn75RY-26t-3D229s&d=DwMFaQ&c=euGZstcaTDllvimEN8b7jXrwqOf-v5A_CdpgnVfiiMM&r=C0bOnd207F99SFw-0e0P-_0YoovOIF4XJSA414HHrZ8&m=A82zCAy_7eCd-ruScZwoOZdhYogMJVWXWe3tOMJ15UOROSqI5kcHRK3amjEcIulM&s=UibF93cn6HO-AtbLOb3swvTiclmufLiI3v2k8zzEzdI&e=Berkeley’s Port Chicago Oral History Project, Meeks said it was reported that the explosion was a “sabotage” mission. He countered that argument, saying that some of the bombs were handled “lackadaisically” by the soldiers. Many of the bombs had to be rolled on and off the ships, causing them to bump against each other if the sailors on the other end didn’t adequately retrieve them, Meeks said from his perspective.

On Feb. 23, 2023, Garamendi, DeSaulnier and U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA-12), presented a House Resolution recognizing the victims of the Port Chicago explosion and the clearing the court martial charges against the African American sailors.

“These 50 courageous sailors have suffered the impact of racial discrimination throughout their service in World War II, and their names have been tainted for 73 years,” Lee said in a February 2023 statement.

“In today’s political climate, we must come together against discrimination and inequality. It is imperative that we rectify this wrongdoing and bring justice to those sailors who made great sacrifices for our nation.”