Celebrating 25 years of success, the Pan African Film Festival (PAFF) kicks off this week on February 9 in Los Angeles at the Director’s Guild of America located at 7920 Sunset Boulevard. Opening night features a red-carpet film screening of “King of Dancehall”, directed by Nick Cannon whom also stars in the film alongside Whoopi Goldberg, Busta Ryhmes, Lou Gossett, Jr. and Kimberley Patterson.

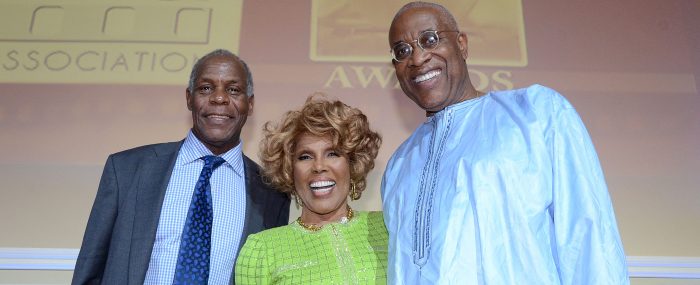

Opening night will also celebrate the work of famed actress Alfre Woodard with The Lifetime Achievement Award, presented by PAFF Co-Founder Ja’net Dubois. Dubois founded the PAFF in 1992 along with legendary actor Danny Glover and Ayuko Babu who serves as the Executive Director.

Besides the opening night screening, all movie screenings and panel discussions will take place for two weeks between February 10 and 20 at the Cinemark Baldwin Hills Crenshaw 15 Theatre located within the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, at 3650 Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. in Los Angeles. Woodard will share her journey with the PAFF audience in a hosted “Conversation with Alfre Woodard,” held on Sunday February 12 at 3pm at the Cinemark Baldwin Hills Theater.

PAFF 25 will screen 202 films, 124 of which are feature-length. The seventy-eight short films screened will be in consideration for Academy Awards as PAFF has been approved as an Academy qualifying festival. Representing 56 countries on 6 different continents, PAFF will proudly screen the largest selection of Black films ever screened at one event.

Having screened the first films of such prominent Black filmmakers as Gina Prince Bythewood (“Beyond the Lights”), Malcolm D. Lee (“Best Man”), Michael Jennings (“Moonlight”), Ava DuVernay (“Selma” &“13th”) and Academy Award winner Gavin Hood (“Tsotsi”); PAFF has also screened films by Raul Peck (“I Am Not Your Negro”), Oscar nominated Mahamat Saleh Haroun (“Gris Gris”) and many others.

The PAFF 25 Artfest will feature 150 major fine artists and clothes designers and jewelers from all over the world. The Artfest will also be held at the Baldwin Hill Crenshaw Plaza.

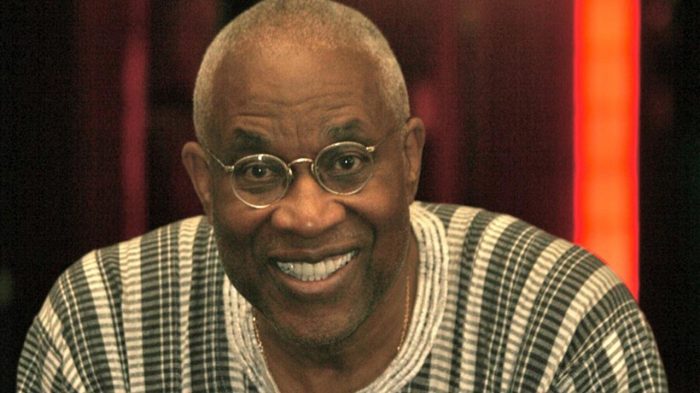

The Los Angeles Sentinel caught up with one of the founding members Ayuko Babu who is an international cultural, political and legal consultant specializing in Pan African affairs. Babu shared with the Sentinel in an exclusive interview the context of how and why the festival was birthed in 1992.

“There was a need after the 60’s decline, we understood that we’ve gotten Black folks to a level to begin to call themselves Black, stop calling themselves negro, to be African-American,” said Babu. “We realized the next step was to raise people’s consciousness and to connect Black folks from around the world to understand our story.”

Babu’s consciousness was transformed and shaped from 1954 and 55 with Brown vs. Board of Education, Emmett Till and through the war on Vietnam.

He was part of the genesis of Black student unions that created Black studies programs on college campuses around the country. Babu shared that Black student unions played a pivotal role in the late great Muhammad Ali having the opportunity to travel and speak on college campuses when he was stripped of his boxing title, sentenced to five years in jail and forced to pay a ten thousand dollar fine. Ali earned tons of cash for his speaking engagements but it’s important to note that without the support of Black student unions across the country and the critical support of the Nation of Islam who supported Ali financially and physically by guarding Ali during the tumultuous time, we might not have witnessed Ali as being one of the greatest orators in modern history.

“I refused to fight in Vietnam they drafted me ten times,” said Babu. “The whole thing and we all said we were not going to fight. We would go to Africa if necessary. We supported the Vietnamese, it wasn’t that I am against the war. The Vietnamese people were correct. It was their land; it was their country. They were right and they were using us to go fight those people and Ali and all of us all said we would not fight.

“We began to realize that this is why we pushed for Black studies,” said Babu. “I was one of the people who helped create Black study centers across the country and Black student unions. I was in SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) and the Black Panther Party and the Black Congress and then I also went to UCLA law school so I was part of that whole experience.

“We knew what was important in this historical moment was a struggle about whose story gets told. Because if you follow the wrong story you follow somebody’s else’s story and they deliberately created that in us to listen to somebody else’s story…and see the frames of us. We knew we needed to hear our story.

“And what that meant was a result of the slave trade and global colonization African people are spread across the planet so a little bit of our story is everywhere. A little bit of it is in Haiti, a little bit of it is in New Orleans, a little bit of it is in Lagos, a little bit of it is in Kenya, a little bit of it is in Papua New Guinea, a little bit of it is in New Zealand and a little bit of it is in Jamaica. We tend to get caught up in our own particular story.

“You can get caught up with, ‘I’m from New York, I’m from L.A., I’m from the Westside. We all get caught up in these little stories but that is just a piece of the story. And if you don’t hear what Lagos is talking about and you don’t hear what New Orleans is talking about than you haven’t heard the whole story and then you can’t integrate the whole story and have a better understanding.”

Babu was part of the great Black migration of folks going north. His parents went to Wyoming where he was raised in Cheyenne and the significant thing about being raised in Cheyenne was there were only 2,000 Black folks in the entire state and 1,000 in the city of Cheyenne which is the capital of the State.

“Raised in that situation we had to go 100 miles to get a Miles (Davis) or James Brown record down to Denver because the radio was all country western,” said Babu. “So we wanted to understand who we were, what we were about and understand ourselves.”

The journey for music gave Babu and his friends a better appreciation for Black culture and Black people because they go out and get it.

“One of the things we noticed and I’ve talked to Taj Mahjal about it, Taj Mahjal who was one of the great blues musicians,” said Babu. “Taj was raised in Great Barrington, Massachusetts like [W.E.B] Dubois. A whole bunch of Black folks come out of small towns. So was Langston Hughes, he was from Joplin, Missouri and so was Richard Pryor he was from Peoria, Illinois.

“So you sometimes think of these Black folks being from the big cities, they really came here because this is where Black folks were. So, what happens is you have more of an appreciation. If you are around a bunch of Black folks and the pathology of Black folks and all that confusion…we came here looking and hungry for the culture. And we also appreciated the culture and could distinguish between the culture and the pathology.”

Babu didn’t move to Los Angeles for the sunshine or for the palm trees, he came to L.A. because Black folks were migrating out here and he wanted to go to school. The next step was for him to travel to Africa and go to the Caribbean because he was on continual search for the African story.

Babu attended L.A. City College, graduated from California State Los Angeles and attended UCLA Law School.

“Being at the university what the university did was this, it brought all Black folks from around the world,” said Babu. “You get a chance to talk to Nigerians, you get a chance to talk to Jamaicans, you get a chance to talk to the Cameroonians, the aborigines because they are all there to get some information and some knowledge. And that’s what the whole universal space is about, information and knowledge. So, that informed us and that led us to join the movement.”

In addition to PAFF, Mr. Babu currently serves as a permanent member of the jury of the annual Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA), headquartered in Lagos, Nigeria. AMAA is the world’s largest Pan African film awards event, covering the continent of Africa and its worldwide Diaspora. In 2016, Mr. Babu was appointed to the California Film Commission.

Currently he is developing formal ties with the National Film and Video Foundation (NFVF) of South Africa, a government agency whose mission is to develop and promote the South African film industry. He also works with the Africano Film Festival in Milan, Italy, the Zanzibar International Film Festival in Tanzania, where he has served as a member of the jury, and the Rwanda Film Festival in Kigali, Rwanda, where he served as a member of the jury.

In past years, Mr. Babu was a consultant to the late Bishop H.H. Brookins, of the African Methodist Episcopal Church when Bishop Brookins’ district covered southern Africa. He was also a consultant to the late Mr. Dick Griffey, President of the African Development Public Investment Corporation and SOLAR Records. In 1977, he was a consultant to Stevie Wonder and helped facilitate Mr. Wonder’s participation at FESTAC (the 2nd Festival of Pan African Arts and Culture) held in Lagos, Nigeria. At FESTAC, among other activities, Mr. Babu helped coordinate the satellite transmission of Mr. Wonder’s GRAMMY appearance from Lagos.

In 1984, he brought the famed Les Ballets Africains de la Republique de Guinee to the Olympics in Los Angeles. He was Co-Chair of the Program Committee for The Nelson Mandela Reception Committee at the Los Angeles Coliseum in 1990, appointed by Congresswoman Maxine Waters.

He has sat on the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Peer Grant Review Panel and the Los Angeles County Arts Commission Grant Review Panel. He has been a member of the Los Angeles Arts Loan Fund review panel. He is currently a member of the Mayor’s African American Heritage Month Committee for the City of Los Angeles.

“I am part of continuum of Black folks that has been going on since Ancient Egypt to protect our story and tell our story and be part of that.

“My legacy is I was a good soldier. Doing what I was supposed to do and thanks to other people showing me what to do in life because there is a way on how you organize your life to end up working on Black folk’s business. I really didn’t want to work on white folk’s business.

“The legacy of the festival is that we are trying to do our part in this period to pass the story on and help expand because we got to really have our own film industry.”

For the PAFF 25 schedule listing and ticket information visit paff.org.