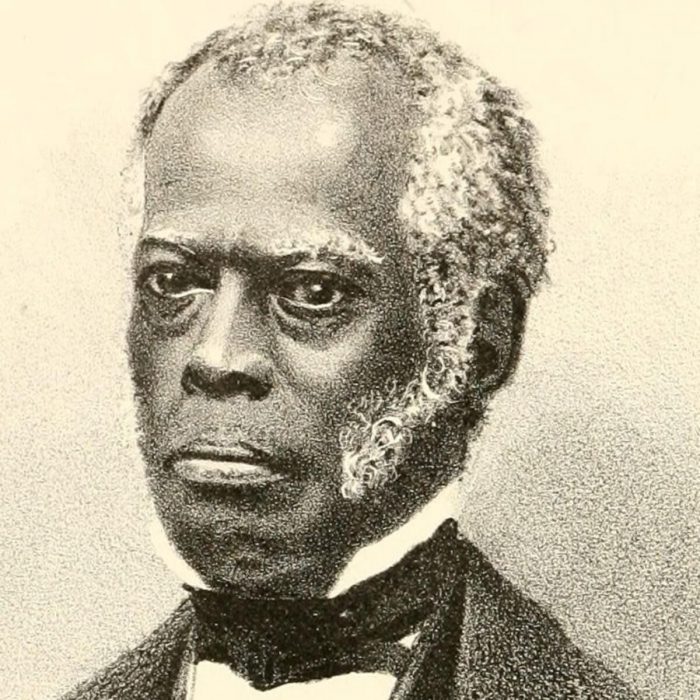

As a young slave, Lunsford Lane glimpsed a path to freedom when he sold a basket of peaches and collected 30 cents, the first money he’d ever touched.

Not long after that, he won a few marbles and sold those, too, adding 60 cents to his pile.

Slowly, Lane built a nest egg out of odd jobs, chopping extra wood at night, selling flavored tobacco and handmade pipes to members of the North Carolina state legislature in Raleigh. He stashed his loot away.

Then in 1835, he bought his freedom for $1,000, a fortune earned through sweat and beatings.

“I cannot describe it,” Lane wrote in his 1842 book “Narrative,” “only it seemed as though I was in heaven. I used to lie awake whole nights thinking of it. And oh, the strange thoughts that passed through my soul, like so many rivers of light; deep and rich were their waves as they rolled; these were more to me than sleep … But I cannot describe my feelings to those who have never been slaves.”

The state approved a historical marker for Lane, the sixth sign in Raleigh to honor a former slave. Sometime in June, said Ansley Wegner of the N.C. Highway Historical Marker Program, the man born property of Sherwood Haywood will be recognized on Edenton Street, just across the street from the Capitol where he sold pipes for 10 cents each.

But even after Lane paid the price, freedom stayed out of reach. A Raleigh judge declared that he had done nothing “meritorious” to earn his freedom, forcing Lane to travel to New York, according to the marker program’s research.

Twice, he tried to relocate in Raleigh, finding no welcome. A state law forbade freed slaves for staying longer than 20 days, so Lane paid to free one of his daughters and fled north. A second time, in 1842, a mob in Raleigh tarred and feathered Lane for giving abolitionist speeches up north, and he escaped to Massachusetts with the rest of his family.

“The thought that I was now in my loved, though recently acquired home, that my family were with me where the stern, cruel, hated hand of slavery could never reach us more … almost overwhelmed me with emotion, and I had a deep and strange communion with my own soul,” Lane wrote in “Narrative.”

Wegner said Raleigh’s marker collection includes five others with backgrounds in slavery: Anna Julia Cooper, Charles Hunter, Edward Johnson, James Harris and James Young.

In his “Narrative,” Lane describes his luck at being a house servant in Raleigh rather than a plantation slave, but still the knowledge that he would always serve another “preyed upon my heart like a never-dying worm.”

Once in Massachusetts, Lane worked in a Union hospital during the Civil War and later sold medicine, the state’s research said. Before dying in 1879, he helped found a school in New Bern, never forgetting that he was once forbidden to hold a book.

“The wine fresh from the clustering grapes never filled so sweet a cup as mine,” Lane wrote, concluding his book. “May I and my family be permitted to drink it, remembering whence it came!”