All photos are copyrighted and may be used by press only for the purpose of news or editorial coverage of Sundance Institute programs. Photos must be accompanied by a credit to the photographer and/or ‘Courtesy of Sundance Institute.’ Unauthorized use, alteration, reproduction or sale of logos and/or photos is strictly prohibited.

If you love jazz or even if you don’t and you know a thing or two about jazz, then you’ve heard the name Miles Davis and if you have not, then, you’ve not been listening or hearing very well

Miles Davis is one of the most significant jazz musicians to ever arrive from the era, no small feat since jazz gave birth to many geniuses of the art form.

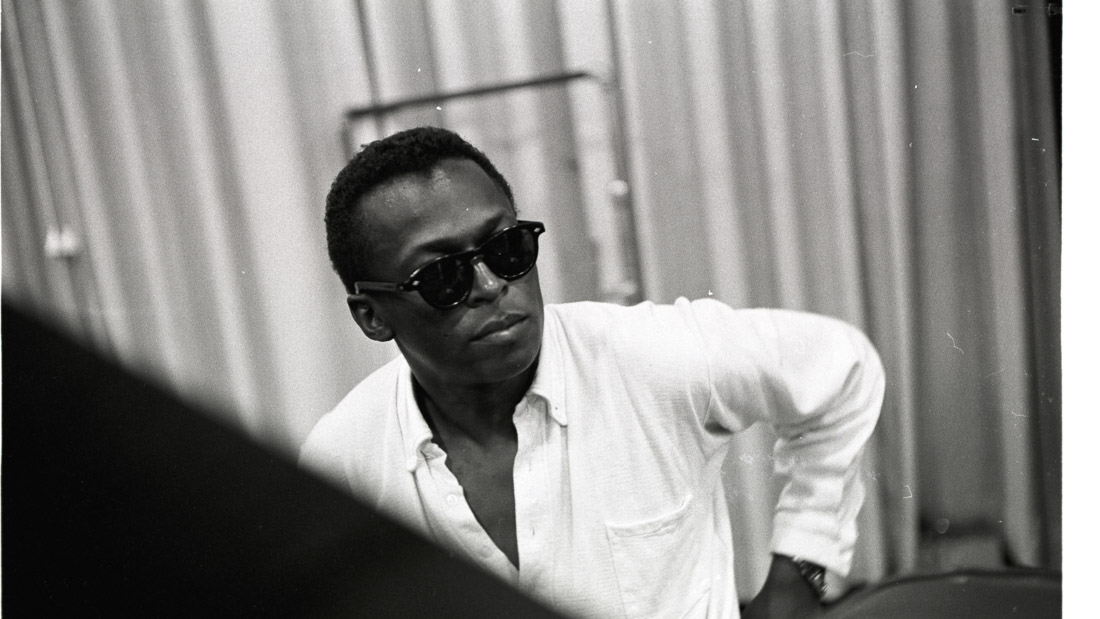

What Davis had, that others made comments upon, even from his earliest days was his “star” quality. That’s high praise since he was coming up with other jazz musicians who in turn also became legends yet they didn’t possess a mystic around their persona. Not like Davis who simply didn’t give an “F” and because of that his mystique only grew more. He burned through the ’50s and sauntered through the ’60s using and abusing, drugs and alcohol and building up his mystique which grew darker, and darker.

Despite his passion for drugs and booze, he found time for women whom he professed to love deeply yet he treated horribly subjecting them to mental and physical abuse.

“Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool” directed by Stanley Nelson (“The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution”) is a very rich and exhilarating look into a man who courted tragedy. Under Nelson, the story is sharply edited with interviews and amazing archival footage which feels as fresh as falling snow. Nelson is just as much a surprise as his subject which he brings to life with such care. The period montages are so well executed it feels like you’re viewing your own forgotten home movies. Narrated by the soulful voice of actor Cal Lumbly, perfectly impersonating a collective memory of Miles’ famous sandpaper raspy voice, as he reads passages from Davis’ autobiography.

Davis’s world, as an African American born in 1926, had limitations but compared to most, he lived with privilege because his father was a dentist and a farmer and the second wealthiest man in Illinois, but that did not shield a young Davis from the evils of Jim Crow. His father chose the trumpet for him and once Davis began playing it, he set his heart on getting to New York City where he read about the jazz clubs on 52nd St.

He made it to New York where he met Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker and while still in his teens, we worked with Billy Eckstine’s swing band. He was young and he was brilliant. He attended Juilliard and he journeyed to Paris, where he was treated as a rising star —equal (for the first time) to White people. He was part of history and he shook hands and broke bread with Sartre and Picasso, and fell in love, with a Parisian actress and singer— Juliette Gréco. That love affair didn’t last long. America called and Davis answered but not happily. On the airplane ride back, he was so unhappy about returning he couldn’t speak. It’s suggested that the depression lead him into his crippling heroin addiction.

A great promise, and because of addiction and depression Davis and at 29, he was making a “come back” after dropping out of Parker’s band. Determined, Davis tore up the stage at the Newport Jazz Festival (1955) and made the recording executives stand up and take notice.

Columbia signed him and he recorded his album in what’s now an example of his brand of Bebop and it’s around this time, the documentary suggests, he stopped “performing” living up to his “F” you image. Hate him, the man, or love him (the man) the music that he produced is cool. History has firmly established that his first album was a jazz-crossover sensation and that it elevated Miles to a level all his own.

At the height of his world success, one late summer night, in 1959, he was arrested by a racist cop because he refused to leave the sidewalk. He was standing outside of Birdland, smoking between sets. The cop hit him in the head. There are images from that night, the incident left him scarred and the photos show a shell-shock Davis. He said it later, in his writing and to those that would listen. “That incident changed me forever,” said Miles Davis. “It made me more bitter and cynical than I might have been.”

Miles used the powerful word “bitter” and it appeared that this played out in other parts of his life especially with Frances Taylor, a talented dancer with an amazing body. She became the love of his life and his muse. In “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool,” she speaks having been interviewed in her late 80s. She tells us that Davis was jealous and when she made a comment that Quincy Jones was “handsome” he hit her and he continued that behavior.

There is a lot to really enjoy about “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool” including great stories about how he actually got his gravely sound (removing polyps from his throat) and how he composed a score to the great filmmaker, Louis Malle’s “Elevator to the Gallows” Here Davis genius is without question. He just watched the film and improvised along with the images.

Time moves on as it does for all of us, and when the ’60s arrived, sadly, the appetite for jazz was dwindling—fast. Davis being Davis, took a listen to the Rock world and wanted a nice fat piece of that bubbling pie. His step into that world was a recording called “Bitches Brew.”

The documentary does not shy away from his addiction or his mental condition, sharing that for six-years, Davis took a long break from playing his horn. He lived inside his home, trying to come back to the music that made him feel alive.

What “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool” does best is capture Mile Davis, all of him, the good, great and the horrible — and the legend —with no excuses.

“Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool” directed by Stanley Nelson. Interviews with Frances Taylor Davis, Juliette Gréco, Stanley Crouch, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Farah Griffin, Gerald Early, Greg Tate, voiced by Carl Lumbly.