In this month of commemoration and celebration of our sacred narrative we know as Black History, I reach back in the spirit of sankofa to retrieve and share an article centering the poetic voice and vision of Nana Lucille Clifton, seeking beauty and deep meaning in this time of urgent resistance and vital affirmation of the goodness we embrace, embody and bring into the world. Indeed, the healing, liberating and uplifting character of her works reminds us that resistance is not only opposition to our oppression and oppressor.

It is also affirmation of our beautiful, sacred and soulful selves and our active aspiration for a new and good-filled world we bring into being in love, striving and struggle in the most elevated, engaging and expansive ways. And it is good to pause and ponder these creative words and wonderfulness by which we mold and make and name and know ourselves. For we are all, in a real sense, both poets and poetry unfolding, and it is from and to each and all of us that Nana Lucille writes, hums and sings her sacred songs.

Lucille Clifton (June 27, 1936 – February 13, 2010) came to the African American Cultural Center (Us), a central and centered place for honoring, exploring and understanding people and things African, and so she entered, not as stranger, but as a welcomed goodness, a poet of clear vision, singing and celebrating herself and our people in insightful, uplifting and wonderful ways.

We read the source of her special gifts as her personal and poetic strivings to come into the fullness of herself and in this process, recognizing and paying relentless homage to the sacredness and expansive meaning of ordinary life. Her aim, she tells us, was a decisive turning that leads to a “shining dark” and being “whole and holy” in the season of herself.

To reach this place of freedom and flowering, she sees the need to liberate herself from the racial, gender and social cages constructed for her. Thus, she says, “If it is the final/ Europe in my mind,/ if in the middle of my life/ I am turning the final turn/ into the shining dark/ let me come to it whole/ and holy/ not afraid/ not lonely/ out of my mother’s life/ into my own.” Moreover, she says, this coming into the fullness of herself is a “turning out of the white cage, turning out of the/ lady cage/ turning at last on a stem like a black fruit/ in my own season…”

Her love is natural and necessary for she is “a love person/ from love people, out of the afrikan sun.” She loves family and friends, neighbors and her people striving, creating special spaces of good and beauty, even in the most ugly and oppressive circumstances.

In a signature poem for her husband, Fred, she writes in intense love and righteous respect: “the look of him/ the beauty of the man/ is his comings and goings from.” She says of his Blackness, “something is black/ in all his instances…” Indeed, “he is a dark/ presence with his friends/ and with his enemies/ always.”

He is for her a filler-to-fullness of good things, a music that sings inside her and exits in every direction. She writes, “He fills/ his wife with children and/ with things she never knew/ so that the sound of him/ comes out of her in all directions.” And because he is the man he is, “his place is never taken.”

But she has also known and knows from other women with reliable and nerve-racking reports, that there are those among us who bring less than the good, given and needed. And she echoes their agony and ache saying, “Demon, demon, you have dumped me/ in the middle of my imagination/ and I am dizzy with spinning from nothing to nothing.” But she and they are not easily undone. For her love is resilient and self-restoring, reflective of an essential and ongoing hopefulness, a durable will and an African way of being in the world.

Love of her people emerges in the rich and varied narrative of herself unfolding and thru poetic portraits of their strength, durability and deep wisdom. She identifies and exalts, “The life thing in us/ that will not let us die” and our ability to bring into being the absent good. Indeed, she says, if “we are lost from the field of flowers, we become a field of flowers.”

Likewise, her poems are of love and homage to Black women as mothers, sisters, children, neighbors, posing them at their best, as models and mirrors of Harriet, Sojourner and grandmothers, reminding themselves and us to struggle, demand respect, “work hard, trust the Gods, love (our) children and wait.”

She wants them to mirror and model the Dahomean woman possessing an assertive dignity that demands recognition, appreciation and respect. She says to them, “listen./ you a wonder./ you a city/ of a woman./ you got a geography of your own./ listen,/ somebody needs a map/ to understand you. Somebody needs direction to move around you.”

She is constantly concerned with the children, the love we give them, the lessons we teach them, and the legacy we leave them. In her “last note to my girls,” she says, “I command you to be/ good runners/ to go with grace/ go well in the dark and/ make for high ground.”

And she reminds her son that his origins are in the love and tender care of his mother and father, telling him, “Here you have come, Bomani,/ an afrikan treasure-man./ may the art in the love that made you/ fill your fingers,/ may the love that made you fill your heart.”

This poet has no tolerance for oppression, injustice and systematic slaughter passed off as civilization, progress and the necessities and collateral damage of war. For her, these are ways of death that call for and justify the killing of everything, including children. Thus, she condemns the oppressor who “only to keep/ his little fear/ . . . kills his cities/ his trees even his children.”

She speaks too of struggle, of insisting on the good, of standing up in the midst of the misery and destruction around us and deciding “to keep running, head up, body attentive, fingers aimed like, darts at the first prize,” regardless of loss, pain, and possible failure.

She urges an expanded responsibility to and for the earth and all in it, a rightful recognition of the brevity and the humbling end of our lives, buried beneath ground and trees. “People who are going to be/ a few years/ bottoms of trees/ bear a responsibility to something/ besides people,” she tells us.

Thus, she is concerned about the destructiveness of war and “war kind of things,” which “are erasing” natural “generations of rice, coal and grasshoppers” and other things, inanimate and animate. Unerased and in place, she says these things “ignored pride/ stood on no hind legs/ begged no water/ stole no bread/ did their own things.”

In the midst of “breaking light,” “tree talk,” “water words” and “dreams that hang in the air like smoke,” Lucille, the carrier of light and a teacher of life to be well-lived, leaves us these messages as a kind of summing up and sending forth. Indeed, we could inscribe them on her monument given their current and enduring relevance.

“Listen,” she says, “we have been ashamed,/ hopeless, tired, mad/ but always/ all ways/ we loved us./ We have always loved each other, children. all ways/ pass it on.” And this too she urges us: “Let there be new flowering/ in the fields let the fields/ turn mellow for the men/ let the men keep tender/ through the time. Let the time be wrested from the war/ let the war be won/ let love be/ at the end.”

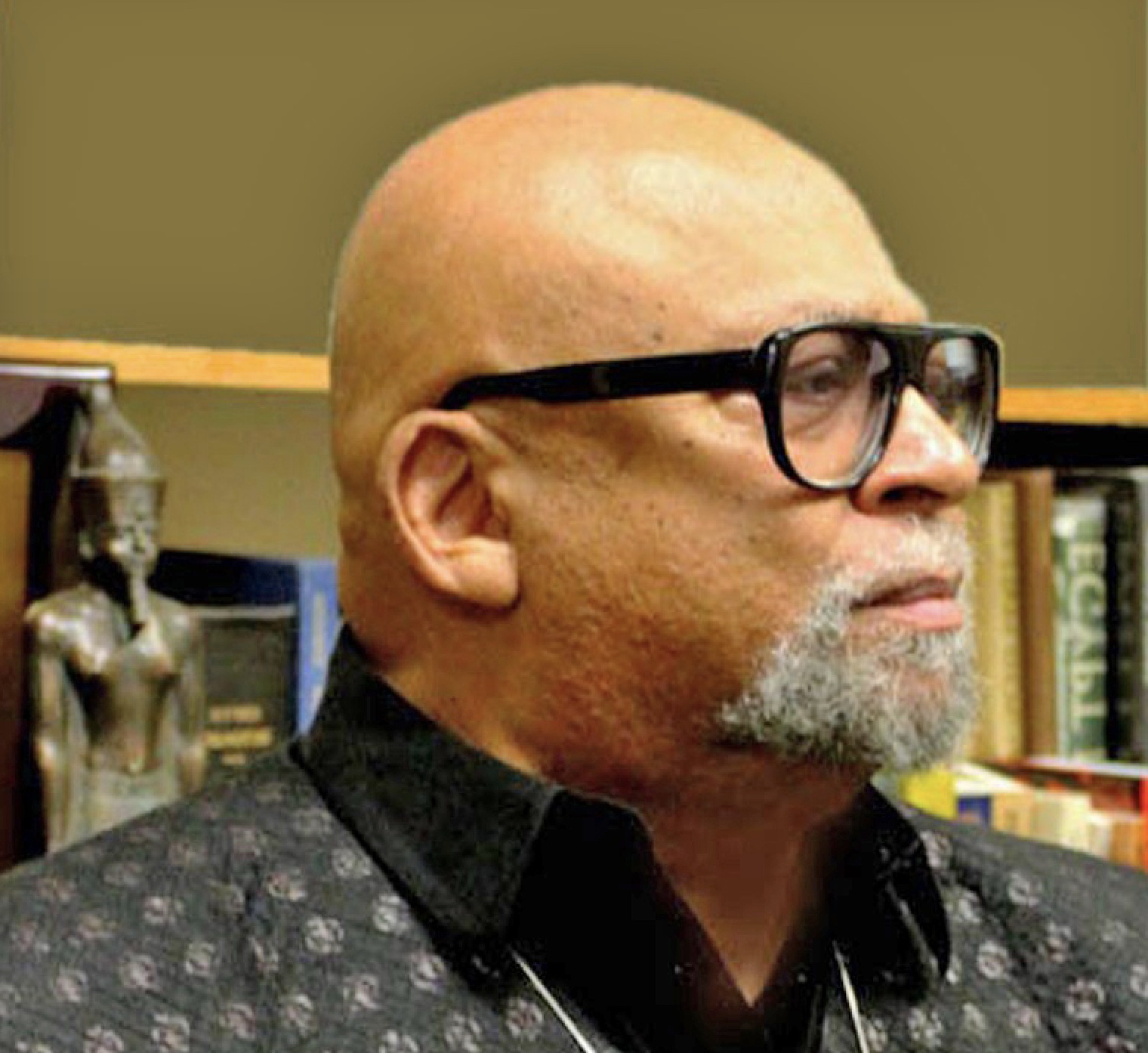

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture; The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.