In discussing Nana Louise Little’s multifaceted and highly formative message to Haji Malcolm which he then gave the world, I began with the lesson of resistance and resilience because it is a lesson that infuses and informs every other aspect of her comprehensive, compelling and committed teaching. Indeed, in the next lesson, resistance and the resilience are required for it to develop and flourish and fulfill its most essential function, that is to say to protect, promote and enhance life and bring good in the world.

I speak here of Nana Louise’s cultivating in Haji Malcolm the discipline and love of learning as another of her life lessons for her children. Indeed, she took seriously not only the early grounding teachings of her grandparents on the value of knowledge and learning but also the teachings of Nana Marcus Garvey on learning and liberation. For he taught the priority of liberating the mind in the struggle for freedom, saying, “Liberate the minds of men and ultimately you will liberate the bodies men”. And as we see, Haji Malcolm engages learning as a practice and promise of freedom.

Her children tell us that she taught Haji Malcolm and them to read and research beyond the classroom, to read widely, to take study seriously, to look up words not known and not pass over them, to keep a dictionary visible and accessible, and to use it regularly. Haji Malcolm would later reenact and expand this disciplined search when he decides he needs a larger vocabulary to study history and the world. For he reports he copied the whole dictionary to expand his capacity to read, learn and reflect on the lessons of history, religion, struggle and life.

Here, I define discipline as a self-imposed order of reasonable restraint and focused and sustained initiative directed toward excellence and development. And Haji Malcolm demonstrated such a discipline, not only in his learning but also in the living of his life, the doing of his work and the waging of our shared liberation struggle.

He tells us he read widely and incessantly, that a whole “new world opened” for him, and “you could not have gotten (him) out of a book with a wedge.” And as learning became a practice of freedom through his learning, he reasoned “I had never been so truly free in my life.” Moreover, it “changed the course of (his) life” and “woke in (him) some dormant craving to be mentally alive.” In a word, he was developing a life of the mind that would serve him well in his emerging and continuing service to our people as he tells us.

Moreover, towards the end of his autobiography and his life, Haji Malcolm muses over his not having had a full “academic education” and talked of his wish that he had become a lawyer and how he would have been a good lawyer, but as we know a white racist teacher discouraged him from that aspiration and achievement. Also, Nana Louise had introduced the children to the practice and promise of being multilingual as she was, speaking at least three languages: Grenadian Creole, French and English.

And like his mother, Haji Malcolm spoke of his “love of languages” and his aspiration, if he had the time, to learn African languages, like Swahili and Hausa, and also, Arabic and even Chinese, anticipating its future role in the world. He concludes, reflecting on the central value of the discipline and love of learning transmitted to him by his beloved mother saying, “I would just like to study. I mean (wide)-ranging study, because I have an open mind” and an unquenchable eagerness to learn.

Thirdly, Haji Malcolm’s mother, Nana Louise, taught Haji Malcolm and all her children self-appreciation and respect and the responsibility of being Black. Clearly, she did this in cooperation with her husband and his father, Nana Earl. But again, she was the first and closest teacher. She taught them as Nana Garvey taught, that “the Black skin is not a badge of shame, but rather a glorious symbol of national greatness,” reflective of millennia of world-transforming work, service and human excellence and achievement.

Haji Malcolm deviated from this path for a while, but in captivity and through the NOI which sacralized Blackness, he came home again. He became, as the Nigerian Muslim students named him in Yoruba, Omowale, “the son who has come home.’ And he said of this sacred naming, “I meant it when I told them I had never received a more treasured honor.”

It is important to note that Nana Louise did not call or claim the white rapist of her mother, as a grandfather. For she knew there is no dignity in attempting to sanitize sexual savagery with pretentious and self-degrading claims of rapist parenthood. Nor did she go on a genealogical journey to look for whites in her background, as if that were a contribution to her history rather than a degradation of her humanity. Indeed, she taught Haji Malcolm to know his history and honor it. And she taught him, he tells us, to not be proud of his light skin and how “she went out of her way never to let me become afflicted with a sense of color-superiority.”

Later, he would criticize any Black daring to think “that he was superior if his complexion showed more white pollution of the slave master.” Like his mother, he valued his Blackness as both in peoplehood terms and as what Nana Mary McLeod Bethune termed us all, “the heirs and custodians of a great legacy civilization” with an obligation to honor it by being ourselves, freeing ourselves and daring to build with others of similar heart and mind a new world.

A committed activist intellectual and Garveyite, Nana Louise also taught her children to be pan-Africanist and have a world encompassing consciousness. It was Nana Garvey who taught the sacred obligation and moral imperative to free Africa and African people. And she home schooled, organized and worked locally, nationally and internationally to achieve this global goal.

From Grenada where she was born to Canada and then the U.S., she taught and lived the pan-African principles of unity, self-determination, self-reliance and institution-building. Her son, Haji Malcolm, honored this legacy by living it, teaching us to recapture our history and identity, and practice sankofa, a rightful return and retrieval of the best of African culture in ways “philosophically, culturally and psychologically” grounded in being African in the world.

Nana Louise had been raised by her grandparents who were from Nigeria, captured, enslaved and then freed. They had taught her this grounding values and when she met and joined the UNIA, the Garvey Movement, she put them into practice and expanded them. As a womanist and freedom fighter, self-determination was for her both principle and practice, a personal and collective commitment.

And she made it a central value of her life, work and struggle. Like other womanists of the Garvey movement: Amy Jacques Garvey, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Henrietta Vinton David, Queen Mother Moore and others, she resisted being limited by the male dominance of the day and created free space to feel, think and act in dignity-affirming, self-determined, self-expansive, and creative and effective ways.

She was raised in a culture of deep memory of resistance, including the Native American rebellions of Grenada, the Fedon and other revolts and resistance, and to struggle for independence and the West Indian Federation. Thus, she was prepared to teach freedom and truth to her children and others; and as she was a living example of resistance and resilience, as a woman, a wife and widow, a political prisoner in an asylum for her self-determined defiance and a movement teacher and soldier winning and holding ground for African people everywhere.

Indeed, Nana Louise was a truth speaker and teacher, not only in word, but also in practice. And this is the comprehensive meaning of Haji Malcolm’s saying of his beloved mother, “all our achievements are mom’s, for she was a most faithful servant of the truth”, taught in a myriad of magnificent, meaningful and enduring ways.

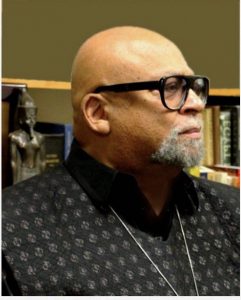

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture; The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.