Now, if cultural grounding is indispensable to our identity, our self-definition, then determining our purpose and direction, of necessity, follow and form a logical link in understanding who we are, what we are to do, and how we are to do it.

The question of purpose speaks to the central mission and meaning in human life. And this, we have repeatedly maintained, is, as our sacred text, Odu Ifa tells us, “to bring and increase good in the world and not let any good be lost.”

Even when we say our Nia (purpose) is “to make our collective vocation the building and developing of our community in order to return our people to their traditional greatness,” it is about bringing good in the world in a particular way and space. And it is reaffirmed in another Kawaida contention that we are struggling for African and human good and the well-being of the world and all in it.

Thus, even as we speak of cultural grounding, we must also be rightfully attentive to moral grounding. This is the meaning of Nana Malcolm’s and Nana Martin’s stress on love of and service and sacrifice for our people and the good of humanity and the world. Dr. King taught that we must be other-directed, saying, “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’” He also said that “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be… This is the interrelated structure of reality.”

Nana King spoke here in both human terms and communal terms. His beloved community, of necessity, begins with his own oppressed and struggling community, us, Black people. But his concept expands and extends to lessons and hope for humanity as a whole.

So, we must start with ourselves, with the humans to whom we owe a primary existence and allegiance. It is not enough, Haji Malcolm taught, to declare our love for humanity; we must first wake up to our own “humanity and heritage” and the lessons they teach us about ourselves. And then we can extend our understanding and respect of the human to other human beings in all their diversities.

He suggests that as we recognize our humanity and the inalienable dignity that defines it, we will not mistreat or wrong ourselves, not be, what he calls, greatly unjust to ourselves. Moral grounding, his teachings tell us, is rooted in our clear and conscious self-recognition of being a representative and expression of the Divine and an accompanying self-conscious commitment not to think or act in ways that violate this special status and meaning.

Thus, we “must recognize each other as brothers and sisters”, speak truth, do justice, be caring, stop engaging in negative practices towards ourselves and others, and expand our efforts to build and strengthen family and community through our righteous and relentless struggle to bring good in our lives and the world, and therefore, “to protect our humanity and project our humanity.”

Indeed, at the heart of Haji Malcolm’s concept of moral grounding is the self-cultivated capacity of “our people to love ourselves, respect ourselves and uplift ourselves” in the process and practice of righteous internal and external struggle to “wake up, clean up and stand up.” We need more knowledge (light), he taught, about ourselves, each other and the world, For he teaches, “light (knowledge) creates understanding, understanding creates love. Love creates patience and patience creates unity,” indispensable to our struggle to defy and defeat the oppressor, end oppression, and build the new and good world we all want and deserve.

Nana King also affirmed his love of and faith in our people, in our people’s capacity and role as a moral and social vanguard. He believed we have “in (our) nature the spiritual and worldly fortitude to eventually win (our) struggle for justice and freedom.” He said, “It is a moral fortitude that has been forged by centuries of oppression.”

And we are compelled to add that it is a moral fortitude forged also by righteous and relentless resistance to centuries of various savage and sustained kinds of oppression. Indeed, we are tested, tempered and formed in struggle. Nana King tells the world that his people, us, in struggle, “have left the valley of despair, they have found strength in struggle, and whether they will live or die, they shall never crawl or retreat.”

Here it is important to note that when we talk of Nana Martin and Nana Malcolm, we immediately must and do remember them as honored martyrs in the cause and interest of freedom, justice and shared good in the world. It is a lesson of supreme love that they gave their lives so we could be and live free, live good and meaningful lives and come into the fullness of ourselves. Thus, they taught in word and life a morality of sacrifice, awesome and instructive.

Nana King calls on us to cultivate a morality of sacrifice, a “dangerous unselfishness.” He says, “We’ve got to give ourselves to the struggle until the end…we’ve got to see it through” regardless of the costs. “Be concerned about your brother” and sister, he urges us in the historic labor strike in Memphis. “You might not be on strike,” yourself, but you and we are all affected in real and meaningful ways. For again and again the lesson is that freedom, justice and all other great goods are indivisible. And thus, he says, “we either go up together or go down” together.

Surely, if we are to map our way forward in culturally grounded and morally grounded ways, in these treacherous and trying times, it will lead us to struggle grounding, grounding in struggle as a cultural tradition and moral imperative. Indeed, our sacred text, the Husia, teaches us that we are morally obligated to bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place, especially among those who have no voice, the devalued, vulnerable, downtrodden and oppressed. It is this, our people’s ancient and ongoing righteous and relentless struggle tradition that Nana Malcolm and Nana King embraced, uplifted and lived.

Nana King tells us we must be willing to sacrifice, suffer and struggle to achieve our goal. He says “Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable… Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering and struggle; the tireless exertions and passionate concerns of dedicated individuals.” For “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” Here, he reaffirms Nana Fannie Lou Hamer’s teaching that in the fierce fight for freedom, “You’ve got to fight. Every step of the way, you’ve got to fight”.

And likewise Nana King reminds us of Nana A. Philip Randolph’s teaching that “Freedom is never granted; it is won. Justice is never given, it is extracted.” And in this same vein, Haji Malcolm teaches that “Nobody can give you freedom. Nobody can give you equality or justice…. If you’re a man, you take it.” That is to say also, if you are a human being. As he states in a praise of Nana Fannie Lou, “You don’t have to be a man to fight for freedom. All you have to do is to be an intelligent human being.”

Finally, Nana Martin and Nana Malcolm reaffirm the essentiality of faith and hope in the struggle for good in the world. Dr. King tells us that “Black (people) in America can provide a new soul force for all Americans, a new expression of the American dream that need not be realized at the expense of other (people) around the world, but a dream of opportunity and life that can be shared with the rest of the world.”

And Haji Malcolm reassures us that if we struggle with a radical refusal to be defeated, we will, in alliance with other oppressed and struggling peoples, win the struggle for a new and good world. And in this new world of shared and inclusive good, which Black people will help reconceive and reconstruct in radically new ways, in this “world of tomorrow, there will be true freedom, justice and equality for all, and that day is coming sooner than you think.” So, we of Us say, let us honor their legacy by living it. That is to say, “continue the struggle; keep the faith; and hold the line”!!!

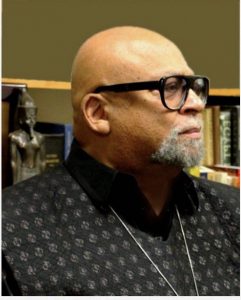

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture; The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.