Continuing to uplift the life and liberating model and mirror Nana Haji Malcolm offers us in this the month of his coming-into-being, I want to draw again from ideas and excerpts from my coming major work, “The Liberation Ethics of Haji Malcolm X, Critical Consciousness, Moral Grounding and Transformative Struggle.”

And I want to focus on the issue of manhood, a central concern in his life, thought and liberating practice. Clearly, one of the major points of departure for critically discussing and discerning Haji Malcolm’s understanding and engagement with the issue of manhood and Black people’s conception of his manhood is the descriptions by the activist-actor, Nana Ossie Davis, of Haji Malcolm and his manhood in both his eulogy for Haji Malcolm and his subsequent statement explaining why he eulogized him.

His definition of Haji Malcolm, as “our own Black shining Prince” and “our living Black manhood,” and Black people’s embrace of this concept, have inspired and informed a central part of the discourse around the meaning of manhood for Haji Malcolm. It also speaks to what it should mean for Black men and Black people as a whole and how it translates into Haji Malcolm’s and Black men’s concepts of and relations with Black women. This is a critical concern, especially as it is discussed in the context of Haji Malcolm’s liberation ethical thought and practice and his changed concept of men and women and their relations of respect with equal rights and reciprocity.

Haji Malcolm’s concept of manhood is both experientially derived and culturally and ethically grounded and affirmed. Given the complexity of his thought and life, I want to focus on his conception in relation to the struggle and the oppressor, and Nana Ossie’s discussion helps to facilitate this mode of engagement.

We can easily concede that his early views of manhood in relation to womanhood was injurious, unjust and flawed, which he himself conceded and had begun to change. Although this has been widely written on, little or no critical discussion has been offered for the possible or real positives in Haji Malcolm’s concerns about manhood, especially in relationship to the contrast and confrontation with the oppressor or the meaning of Nana Ossie Davis’s statement on Haji Malcolm’s manhood to the masses. My considered assumption is that it would be of value to explore these issues and thus I’d like to engage them here.

When Nana Ossie Davis, in his eulogy for Haji Malcolm, calls him “a Prince – our own Black shining Prince! – who didn’t hesitate to die for us, because he loved us so,” he is speaking not of a hereditary political status derived from a royal sovereign. Rather, he is using an honorific, a praise name, to indicate Malcolm’s earned and elevated status of profound respect, based on his people’s assessment of his commitment, character and conduct in righteous struggle and self-sacrificing service to them and the world.

It is above all a moral evaluation and naming, and parallels and intersects with Nana Marcus Garvey’s teaching on an aristocracy not based on hereditary claims or membership in a power elite. On the contrary, Nana Garvey states that in the redemption and liberation of Africa, an aristocracy will be developed not of “privileged positions to inflict on the race” and “at the expense of the masses.”

Rather, “it shall be based on service and loyalty to the race,” to the people and their struggle to liberate and uplift themselves. Likewise, this moral concept of aristocracy and/or royalty resonates with and reaffirms the Kawaida contention that “there is no royalty except in righteousness, no one more worthy of respect than the doer-of-good in the world.”

Moreover, this concept of royalty is also, in both NOI Muslim and Black Liberation Movement discourse of king and queen, an important way of conferring respect, expressing, and demonstrating a valuing of one another. Like the use of the terms “brother” and “sister” in the thickest sense, it carries a moral category of appreciation and solidarity of a people rising up from degradation by the oppressor.

Thus, men and women are addressed and referred to as kings and queens, princesses and princes to suggest a variety of respect-showing appellations such as: royal, honored and honorable, aristocratic and dignified, noble, worthy and elevated – in both a moral and social sense in Muslim, Garveyite and general Black Freedom Movement discourse. And finally, in Muslim and Movement discourse, royalty references speak to an historical and genealogical claim that African descendant peoples are descendants of kings and queens both in a literal, moral and social sense.

And it was/is a claim not only to counteract the deculturalization and inferiorization process of the Holocaust of enslavement and subsequent similar oppression, but also to reaffirm African humanity and worthiness and their human excellence and achievement in human history.

In Haji Malcolm’s lectures on Black history and elsewhere, such references to kings, queens, royal and noble persons are not only used in both a historical/genealogical sense to indicate the royal and noble roots of Black people, but also to indicate both a high level of social and moral achievement. And it also becomes, in its most moral and memory-honoring sense, a call and challenge to measure up in practice to be worthy of a royal and noble status.

Thus, Nana Ossie Davis is not talking without an inherited historical and cultural script and precedence, but is drawing from and building on a long history and modes of cultural reaffirmation and resistance in using the honorific title and praise name, “a Prince, our own Black shining Prince! – who didn’t hesitate to die for us, because he loved us so.”

There are at least three ways we can understand and appreciate Nana Ossie’s assertion that “Malcolm was our manhood, our living, Black manhood. This was the meaning of his people. And in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves.”

The first meaning is that Haji Malcolm modeled and represented Black manhood at its best in its various positive understandings, i.e., as a provider, protector, a morally and spiritually grounded family man, committed to our liberation, uncompromising, witness and warrior for his people, and courageous and fierce in the face of the enemy without backing down. Here we can argue over the meaning of these attributes, but Nana Ossie would clearly support this reading, as well as many others.

Secondly, since Nana Ossie said, “our living Black manhood,” that “this was his meaning to his people” and that “in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves,” he seems also to be using it and indeed “Black manhood” as a metaphor for Black personhood and Black peoplehood. For these virtues and character traits attributed to Haji Malcolm and other men like him can be and are attributed to Black women and Black people as a whole.

As a progressive activist-actor, modelling this in his relationship with his equally progressive and activist actor wife, Nana Ruby Dee, Nana Ossie offers us ground to assume a wider meaning for manhood here than “maleness,” isolated, unlinked and committed to a patriarchal, sexist and limited concept of the category’s “man” and “manhood.” Indeed, he could not possibly mean, either morally or rationally, that what men and boys offer women and girls at their best is their physical maleness as manliness.

Thirdly, it is Haji Malcolm’s humanity, his respect-inspiring courage, commitment, self-determination, defiant resistance, and other virtues that define him and which women and men, girls and boys can aspire to achieve. And it is also an unapologetic particularized appreciation of the unique and equally valid and valuable way of his and his people’s being human in the world, i.e., African, Black man or woman.

Indeed, Haji Malcolm is posed as the model of Black personhood and Black peoplehood, as well as our humanity which Haji Malcolm himself calls for in his liberation ethics. That is one who woke up, cleaned up and defiantly stood up. In other words, he possessed critical consciousness, was morally grounded and was engaged in an ongoing righteous and radically transformative striving and struggle for a new and ‘nother rightful way of being Black man or woman and human in the world.

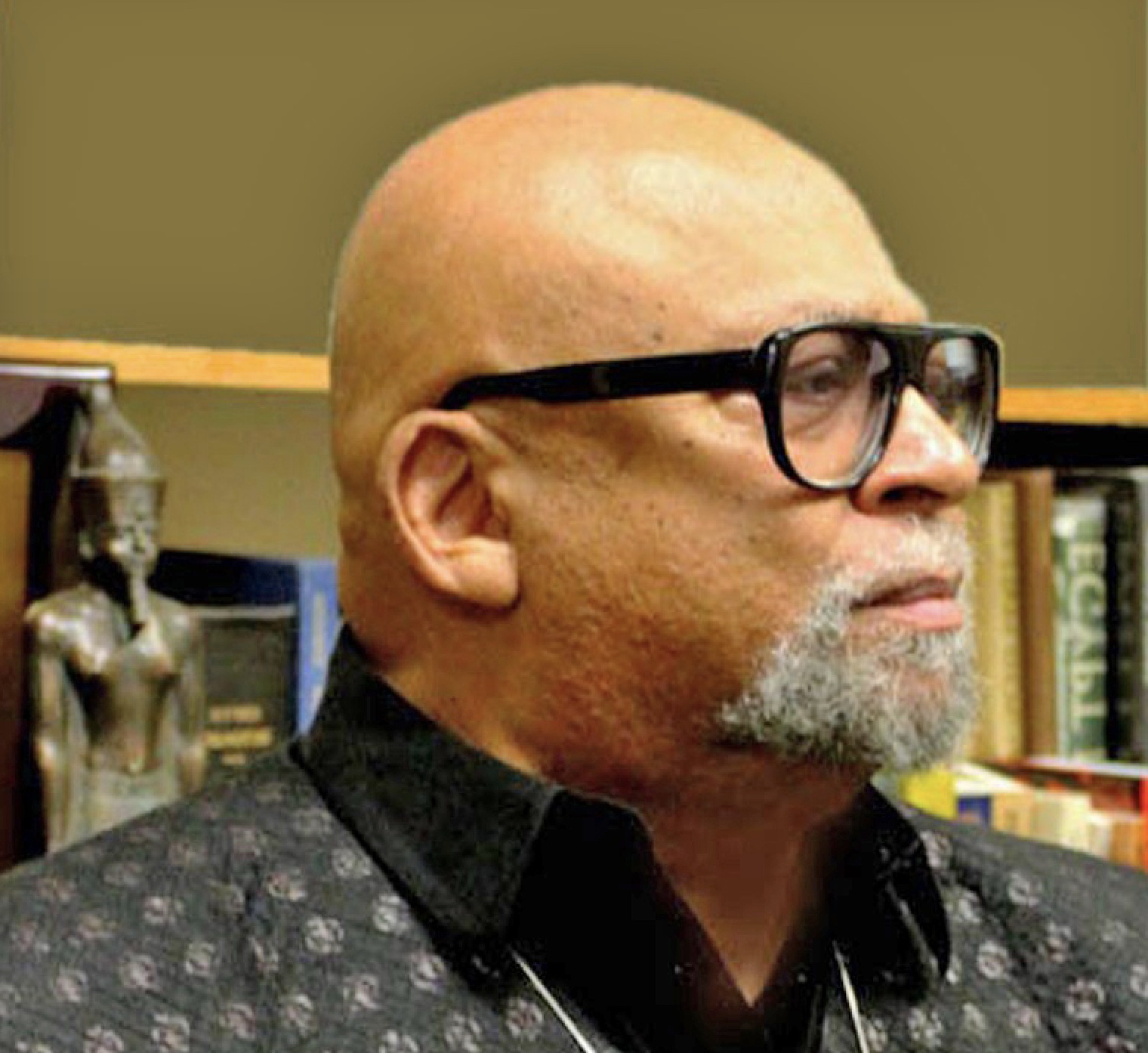

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.MaulanaKarenga.org; www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.Us-Organization.org.