Facebook removed more than 3 billion fake accounts from October to March, twice as many as the previous six months, the company said Thursday.

Nearly all of them were caught before they had a chance to become “active” users of the social network.

In a new report, Facebook said it saw a “steep increase” in the creation of abusive, fake accounts. While most of these fake accounts were blocked “within minutes” of their creation, the company said this increase of “automated attacks” by bad actors meant not only that it caught more of the fake accounts, but that more of them slipped through the cracks.

As a result, the company estimates that 5% of its 2.4 billion monthly active users are fake accounts, or about 119 million. This is up from an estimated 3% to 4% in the previous six-month report.

The increase shows the challenges Facebook faces in removing accounts created by computers to spread spam, fake news and other objectionable material. Even as Facebook’s detection tools get better, so do the efforts by the creators of these fake accounts.

The new numbers come as the company grapples with challenge after challenge, ranging from fake news to Facebook’s role in elections interference, hate speech and incitement to violence in the U.S., Myanmar, India and elsewhere.

Facebook also said Thursday that it removed more than 7 million posts, photos and other material because it violated its rules against hate speech.

Facebook employs thousands of people to review posts, photos, comments and videos for violations. Some things are also detected without humans, using artificial intelligence. Both humans and AI make mistakes and Facebook has been accused of political bias as well as ham-fisted removals of posts discussing _ rather than promoting _ racism.

A thorny issue for Facebook is its lack of procedures for authenticating the identities of those setting up accounts. Only in instances where a user has been booted off the service and won an appeal to be reinstated does it ask to see ID documents.

While some have argued for stricter authentication on social media services, the issue is thorny. People including U.N. free expression rapporteur David Kaye say it’s important to allow pseudonymous speech online for human rights activists and others whose lives could otherwise be endangered.

Dipayan Ghosh, a former Facebook employee and White House tech policy adviser who is currently a Harvard fellow, said absent greater transparency from Facebook there is no way of knowing whether its improved automated detection is doing a better job of containing the disinformation problem.

“We lack public transparency into the scale of disinformation operations on Facebook in the first place,” he said.

And even if just 5 million accounts escaped through the cracks, Ghosh added, how much hate speech and disinformation are they spreading through bots “that subvert the democratic process by injecting chaos into our political discourse?”

“The only way to address this problem in the long term is for government to intervene and compel transparency into these platform operations and privacy for the end consumer,” he said.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has called for government regulation to decide what should be considered harmful content and on other issues. But at least in the U.S., government regulation of speech could run into First Amendment hurdles.

And what regulation might look like _ and whether the companies, lawmakers, privacy and free speech advocates and others will agree on what it should look like _ is not clear.

Of the 3.4 billion accounts removed in the six-month period, 1.2 billion came during the fourth quarter of 2018 and 2.2 billion during the first quarter of this year. More than 99 percent of these were disabled before someone reported them to the company. In the April-September period last year, Facebook blocked 1.5 billion accounts.

Facebook attributed the spike in the removed accounts to “automated attacks by bad actors who attempt to create large volumes of accounts at one time.” The company declined to say where these attacks originated, only that they were from different parts of the world.

Facebook removed more than 3 billion fake accounts from October to March, twice as many as the previous six months, the company said Thursday.

Nearly all of them were caught before they had a chance to become “active” users of the social network.

In a new report, Facebook said it saw a “steep increase” in the creation of abusive, fake accounts. While most of these fake accounts were blocked “within minutes” of their creation, the company said this increase of “automated attacks” by bad actors meant not only that it caught more of the fake accounts, but that more of them slipped through the cracks.

As a result, the company estimates that 5% of its 2.4 billion monthly active users are fake accounts, or about 119 million. This is up from an estimated 3% to 4% in the previous six-month report.

The increase shows the challenges Facebook faces in removing accounts created by computers to spread spam, fake news and other objectionable material. Even as Facebook’s detection tools get better, so do the efforts by the creators of these fake accounts.

The new numbers come as the company grapples with challenge after challenge, ranging from fake news to Facebook’s role in elections interference, hate speech and incitement to violence in the U.S., Myanmar, India and elsewhere.

Facebook also said Thursday that it removed more than 7 million posts, photos and other material because it violated its rules against hate speech.

Facebook employs thousands of people to review posts, photos, comments and videos for violations. Some things are also detected without humans, using artificial intelligence. Both humans and AI make mistakes and Facebook has been accused of political bias as well as ham-fisted removals of posts discussing _ rather than promoting _ racism.

A thorny issue for Facebook is its lack of procedures for authenticating the identities of those setting up accounts. Only in instances where a user has been booted off the service and won an appeal to be reinstated does it ask to see ID documents.

While some have argued for stricter authentication on social media services, the issue is thorny. People including U.N. free expression rapporteur David Kaye say it’s important to allow pseudonymous speech online for human rights activists and others whose lives could otherwise be endangered.

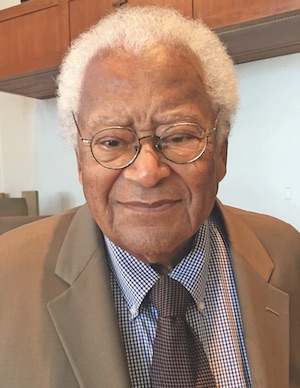

Dipayan Ghosh, a former Facebook employee and White House tech policy adviser who is currently a Harvard fellow, said absent greater transparency from Facebook there is no way of knowing whether its improved automated detection is doing a better job of containing the disinformation problem.

“We lack public transparency into the scale of disinformation operations on Facebook in the first place,” he said.

And even if just 5 million accounts escaped through the cracks, Ghosh added, how much hate speech and disinformation are they spreading through bots “that subvert the democratic process by injecting chaos into our political discourse?”

“The only way to address this problem in the long term is for government to intervene and compel transparency into these platform operations and privacy for the end consumer,” he said.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has called for government regulation to decide what should be considered harmful content and on other issues. But at least in the U.S., government regulation of speech could run into First Amendment hurdles.

And what regulation might look like _ and whether the companies, lawmakers, privacy and free speech advocates and others will agree on what it should look like _ is not clear.

Of the 3.4 billion accounts removed in the six-month period, 1.2 billion came during the fourth quarter of 2018 and 2.2 billion during the first quarter of this year. More than 99 percent of these were disabled before someone reported them to the company. In the April-September period last year, Facebook blocked 1.5 billion accounts.

Facebook attributed the spike in the removed accounts to “automated attacks by bad actors who attempt to create large volumes of accounts at one time.” The company declined to say where these attacks originated, only that they were from different parts of the world.