Clearly, a critical and compelling task of our times is to remember, raise up and reaffirm in our sensitivities, thought and practice our culture of striving and struggle as a people, for the needs of our people, the character of the times and the current course of historical events demand it. And we must remember that we must come to the table and tasks of this urgent and demanding moment, not naked and in need, but fully clothed in our own culture.

For in the midst of this most ancient, rich and resourceful culture are sacred teachings full of instructive insights about how to live our lives, do our work and wage our internal and external struggles to strengthen and develop ourselves, sustain ourselves in struggle and ultimately achieve victory, regardless of the odds and adversaries against us.

Here, I want to revisit the teachings of three honored ancestors, Seba Maat, teachers of the good, the right and the possible, who present us with a powerful portrait of ourselves as persons and a people which is awesomely uplifting and extremely valuable in these difficult, demanding and dangerous times. And I will focus on three concepts offered in their portraits of us as the essential foundation and framework for this piece.

They are Nana Howard Thurman’s concept of us as a people who have “ridden the storm and remained intact; Nana Gwen Brooks’ concept of us as a people who have and must continue to “conduct (our) blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind;” and Nana Nannie Burrough’s concept of us as a people who “specialize in the wholly impossible.”

It is these defining portraits and the accompanying challenges and responsibilities they represent that merit our remembrance and reflection and speak to our urgent need and capacity for righteous resistance and unrelenting resilience in these times. Indeed, it is indispensable to our weathering the savage and sustained winter storms, whirlwinds and seemingly impossible odds against us promised and planned by the incoming regime of right-wing wreckers, vengeful renegades and political raptors.

We are talking here, then, about our people’s extraordinary and enduring capacity for resistance and resilience and our need to remember and reflect on this internal strength and draw from it to deal with the coming storms, whirlwinds and the seemingly impossible odds amassing against us in this era of resurgent White supremacy, masking as saving America and other Hitlerian big lies. Here, we remember and reflect on our capacity to endure and overcome the hell and horror of the Holocaust of enslavement, the sustained savagery of segregation, and the ongoing violence, deprivation and degradation of systemic racism.

And we extract strength from the memory of what we have done and achieved, our overcoming against the odds, our “singing sunshine,” courage and continuing commitment in the dead of night, and our struggling to hurry the dawn of a new day coming, called freedom and shared goodness in the world. Again it is important to note that the Kawaida definition of resistance is not simply opposition, but also affirmation and aspiration. It is opposition to the oppressor and oppression; affirmation of ourselves in our beauty, sacredness and soulfulness; and aspiration, an expansive and liberating vision and struggle for a new world and way forward.

Nana Howard Thurman, prophet, professor, theologian, mystic and deep thinker tells and teaches us that if we are to ride the storms and remain intact, our resilience and resistance must be rooted deeply in a disciplined spirituality, a profound commitment to the transcendent, the moral, the creative and the good. It is a spirituality that is concerned with the transcendent, the divine, at its highest level, but also concerned with life at its everyday, ordinary and even lower and lesser levels. He is concerned about measuring a society by how it treats the least among us, the disinherited, devalued and oppressed.

And he is equally concerned that the disinherited and oppressed value themselves and refuse to surrender their humanity and conception of themselves to others who would undermine and alter it from the dignity-bearing, divine endowment that defines it and demands deep respect. He tells us that “Anyone who permits another to determine his inner life gives into the hands of the other the keys to his destiny.”

Here the Kawaida critical contention is that our oppressor cannot be our teacher and even our allies cannot be our tutors in issues life and death, and vital issues concerning our interests, identity, destiny and daily lives. On the contrary, we must reach inside ourselves as persons and a people, and reaffirm our capacity to be self-defining, self-determining and self-authorizing, and to be ourselves, free ourselves, develop, flourish and come into the fullness of ourselves.

Nana Thurman wants us, in the midst of evil, stress and strain, to call into play “the daring of the spirit that puts to rout the evil deed and decadent unfaith, (and) the experiencing of new purpose which give courage to the weak, hope to the despairing (and) life to those burdened.” We must, he urges us, choose to be, to act, to do the good. Indeed, “under the pressure of crisis when we need all vitality,” we must struggle not to close down and become inactive. For in such a context “what the world needs is more people to come alive,” be active and joyful in the daring and doing of good.

Moreover, he teaches that we must break through the barrier and set aside the baggage of hurry and worry, haste and waste, routine and ruts of daily life. We must carve out adequate time to center ourselves, think deep, and renew and reaffirm ourselves. And he emphasizes that “It takes time to cultivate the mind. It takes time to grow in wisdom…and it takes time to feel one’s way into oneself.”

To feel our way into ourselves is a deep, meaningful and beautiful concept which I read as striving to come into knowledge of ourselves, our strengths and weaknesses, our essential and non-essential, even useless, sensitivities, thoughts and practices. And having achieved this vital understanding, we self-consciously strive to overcome the weak, and set aside the trivia, trash and harmful, so that we can realize ourselves, i.e., know ourselves and achieve ourselves in our fullness.

In our quest for the good and as a defense against despair in difficulty, demanding and dangerous times, Nana Thurman teaches and encourages us to embrace a profound commitment to the “upward reach of life,” faith in the constant triumph of life over death, of good over evil, justice over injustice and freedom over unfreedom. It is this understanding and faith for him that is “the basis of hope in moments of despair, the incentive to carry on when times are out of joint and men have lost their reason, the source of confidence when worlds crash and dreams whiten into ash.”

Finally, Nana Thurman tells us that if we are able to develop a deep and disciplined spirituality, which undergirds and informs our consciousness, courage and commitment, we can ride out any storm and remain intact, spiritually and morally grounded and always reaching upward. And he says, “it is good to know what there in us that is strong and solidly rooted. It is good to have the assurance that can only come from having ridden the storm and remained intact.”

And in this process and practice, we reaffirm our capacity for both resistance and resilience, honoring the often-proved praise names of our people of storm riders and waymakers, modelling and mirroring the best of what it means to be African and human in any and all situations and seasons in this ever-changing world.

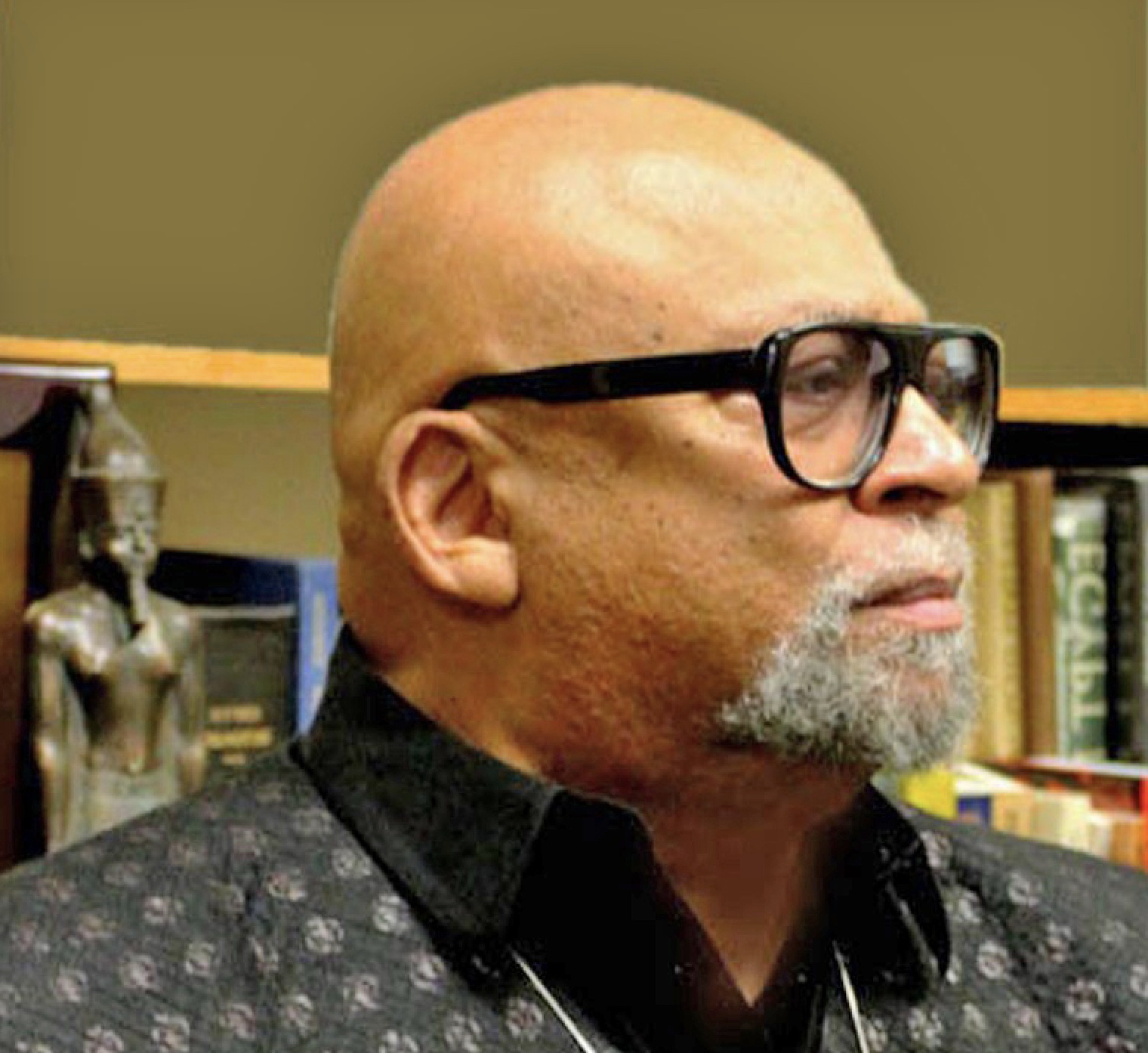

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.