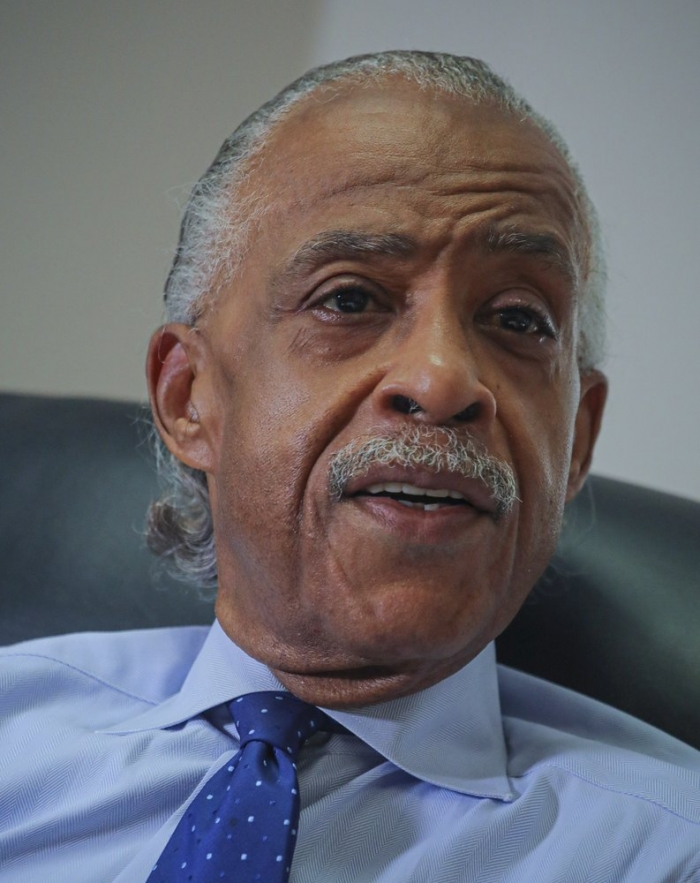

The Rev. Al Sharpton sat quietly in his office in late July, watching the final funeral service for Rep. John Lewis on a wall-mounted television.

Instead of flying down to the memorial in Atlanta, Sharpton had remained in New York; he had work to do. Preaching at the funeral of a year-old boy who was shot in the stomach at a Brooklyn cookout — a boy not much younger than his first and only grandson — Sharpton demanded gun control, an issue close to Lewis’ heart.

He also was embroiled in putting together this week’s commemoration of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This protest will focus on police violence, and its ever-expanding roll call of victims: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rashard Brooks, Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Jacob Blake, among others.

But Sharpton knows he will also encounter the ghosts of another era on the steps of the Lincoln Monument, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed that he had a dream.

Sharpton said he had always felt a kinship with people like Lewis, who had been the last surviving speaker from the original march; the late former NAACP chairman Julian Bond; his own mentor, the Rev. Jesse Jackson. All, he said, had instilled in him the value of discipline and reverence of principles of nonviolent resistance espoused by King.

Lewis, Bond and so many others are dead; at 78, Jackson clearly is not the lion he once was.

But Sharpton — once dismissed by some as a fraud, a jester — is still standing. He reaches multitudes on television and on radio. The man who helped popularize the 1980s cry, “No justice, no peace,” is putting himself at the center of a new wave of activism, in a new millennium.

“I want to be able to show that the movement is not dead,” said the Rev. Al.

___

For more than three decades, Sharpton, 65, has been a go-to advocate for Black American families seeking justice and peace in the wake of violence and countless incidents that highlight systemic racism. He has a penchant for seizing the national spotlight and focusing the public on police brutality and acts of hatred against Black people, particularly at moments of heightened tensions and grief.

But Sharpton now contends with a new question: In what shape will he leave the world for Marcus Al Sharpton Bright, the only male heir to the family legacy?

“I never thought I’d live to see my grandchild,” Sharpton said recently in an interview at the midtown Manhattan offices of National Action Network, the civil rights organization he founded in 1991.

“In many ways, every time I see him, I know it’s a blessing God gave me that he didn’t give some of the civil rights leaders before me,” Sharpton said. “I’m hopeful and I’m challenged … What kind of society am I leaving him where you can get shot by the cops and the robbers?”

Sharpton has embraced the resonance of Black Lives Matter — it’s now said to be the largest protest movement in U.S. history. But he takes issue with people who claim that the leaderless, decentralized nature of the emerging movement is an entirely new phenomenon.

“One of the follies of youth, including me when I was young, is you think you’re the first one to do what you do,” Sharpton said. “There ain’t nothing new. If you don’t have that kind of back and forward (over tactics), which Dr. King used to call creative tension, then you ain’t got no movement.”

“I expect there’s going to be alternatives to me,” he added. “And it’s good, because it’ll bring a synthesis and because nobody’s got all the answers.”

Born in 1954 in Brooklyn, Sharpton quickly showed promise as a preacher. At age 4, he delivered his first sermon; he was an ordained minister by age 10.

When he was just 13, Jesse Jackson appointed Sharpton youth director of New York’s Operation Breadbasket, an anti-poverty project of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The Al Sharpton who grabbed the spotlight in the 1980s was a rotund young man in a track suit, his neck garlanded by a chain and medallion and his hair in a pompadour — a remnant of his days as James Brown’s tour manager.

Sharpton constantly courted controversy for using inflammatory language against his opponents. He reserved his most fiery rhetoric for elected officials and attorneys representing police officers and alleged assailants in case after case of racial violence.

In 1989, Sharpton’s attention was drawn to the death of Yusuf Hawkins, a Black teenager fatally shot after being confronted by a mob of white youths in Bensonhurst, a historically Italian-American neighborhood of Brooklyn.

As explored in the recent HBO documentary, “Storm Over Brooklyn,” Sharpton’s work on the Hawkins case was widely seen as the main cause of flared tensions between Black and white communities in New York City. In 1991, as he prepared to lead a march through Bensonhurst with the Hawkins family, a white man stabbed Sharpton in the chest.

But many people, particularly those turned off by Sharpton’s brash tactics, know him for his role in publicizing the case of Tawana Brawley, 15-year-old Black girl who in 1987 accused six white men, including police officers, of assault and rape in upstate New York. A grand jury later found evidence that Brawley had fabricated the story, after which Sharpton and two attorneys who joined in the case were ordered to pay damages to the prosecutor who sued for over defamatory statements.

Sharpton was hardly the only prominent New York figure who believed Brawley’s story. But even today, some of Sharpton’s critics will bring up the case to discredit him.

Asked if he had any regrets about that period of his life, Sharpton said he “would have looked into situations more deeply before getting involved.”

“Sometimes your vanity outruns your sanity, and you do things for posture. But it’s all part of growing up.”

___

Sharpton came to be known as a political strategist skilled at staging direct-action protests, while adhering to King’s principles of nonviolence. Although few of his critics would classify his tactics and rhetoric as entirely civil or peaceful, Sharpton is the reason why Amadou Diallo, Abner Louima and Sean Bell, Black men killed or brutalized by police in New York City, became household names long before the advent of social media and hashtags.

“I had core beliefs and I could work with different eras” of the movement, Sharpton said. “I was always free enough — never took government funds, never held office — I was free enough to flow. I think being willing to adopt everything, but my core beliefs, is the strength of my longevity.”

Today, the track suits and chains are long gone, replaced by tailored suits over a frame less than half the size of what it once was. But the fire is still there.

Sharpton was among the civil rights leaders who flew into Minneapolis for the first of the memorial services for Floyd, who died May 25 after a white police officer held his knee to the man’s neck for nearly eight minutes even after he was unresponsive. It was at that service, amid Hollywood celebrities, federal lawmakers and activists, that Sharpton both announced and found the theme to Friday’s march commemoration.

“George Floyd’s story has been the story of Black folks,” he said. “Because ever since 401 years ago, the reason we could never be who we wanted and dreamed to be is you kept your knee on our neck.”

“It’s time for us to stand up in George’s name and say, ‘Get your knee off our necks!’”

The refrain resounded, as protests and civil unrest gripped the nation that seemed to be awakening to issues Sharpton had preached about for decades.

Sharpton has been an activist long enough to have inspired acolytes. National civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump, who has represented the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and dozens of other victims of police brutality and vigilante violence, credits Sharpton with charting a path that made it easier for up-and-coming activists and lawyers to be heard.

“Rev. Al has been a mentor to me for many years,” Crump said in a phone interview. “Long before there was Black Lives Matter, you had Rev. Al Sharpton out there saying this life mattered, when everybody else was trying to marginalize it and sweep it under the rug.”

“He’s a teacher and he made some of the mistakes that we don’t have to make,” said Lee Merritt, another prominent civil rights attorney who has represented the families of Ahmaud Arbery, Botham Jean and Atatiana Jefferson, among others.

“A lot of people feel like (the work) is about public outcry, but if you don’t get to the root of the issue, if you don’t go after the systemic racism and the policies that allow this to happen over and over again, then you’re going to be disappointed when it’s all said and done,” Merritt added.

Twenty-three-year-old Tylik McMillan first started working for the National Action Network 10 years ago. Now the group’s national director of youth and college, McMillan said Sharpton prepared him to act as a field organizer for Friday’s March on Washington.

“He has always been such a compassionate leader, a hard leader that builds character,” McMillan said. “He’s giving me an understanding of what it means to move from demonstration to legislation.”

Which is the point of the march on Washington: Sharpton has made passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act a central demand.

In June, the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives passed the Floyd act, which would ban police use of stranglehold maneuvers and end qualified immunity for officers, among other reforms. In July, following Lewis’ death, Democratic senators reintroduced legislation that would restore a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 requiring states with a record of voter suppression to seek federal clearance before changing voter regulations. The U.S. Supreme Court gutted the provision in 2013.

The march, Sharpton said, isn’t simply for the cameras.

“If you’ve got a march without an objective, then you’ve got an exercise class going on,” Sharpton says.

___

The House of Justice, Sharpton’s storefront auditorium and headquarters off of Malcolm X Boulevard in Harlem, buzzed with activity on Saturday morning in late August. There is a rally each week; afterward, Sharpton personally hands out bagged meals to a line of people that stretches up 145th Street, part of an ongoing coronavirus pandemic relief effort.

Gwen Carr, mother of Eric Garner, a Black man whose chokehold death by NYPD in 2014 fueled Black Lives Matter protests in New York and across the country, is a regular at the rallies. She said Sharpton stuck close to her family, particularly when the cameras and probing reporters

went away, through the years it took local and federal law enforcement agencies to conduct investigations that eventually led to an officer’s firing.

“A lot of people listen to the controversy about Rev. Al, and they don’t know him as a person,” Carr said. “They just listen to what other people are saying about him, and I think that’s very wrong.”

“He does a lot for families that’s not in the public eye,” she added. “Some people think it’s just about police brutality, but it could be housing injustice. It could be a crisis because a family’s lights are getting cut off.”

Still, Sharpton’s daughters, Ashley Sharpton, 32, and Dominique Sharpton Bright, 34, said their father’s public image isn’t much different than the one they’d experienced over the dinner table.

“As I grew up, I realized this is not a persona,” said Ashley Sharpton, who founded the National Action Network’s Youth Move Huddle initiative that engages young adults who aspire to be community leaders.

“We sacrificed our dad to the movement,” she added. “That was heavy for me to understand. That took a while for me to accept.”

But something has softened in their dad since he became a grandfather, said Bright, Marcus Al’s mom and national membership director for the National Action Network.

“It’s so weird to see it because he kind of steps out of who he is to relate to Marcus Al,” she said.

“I remember when he was 4 months old and dad was like, ‘Is he talking yet? Is he walking?’” Ashley Sharpton said. Her dad “has been preaching since he was 4. So, I’m sure it’s an eagerness to see if any of that translated.”

There are many things that still keep the reverend away from home — he’s organizing, preaching, consoling. He hosts “PoliticsNation” on MSNBC, which reaches about 2 million viewers every weekend, and he has a nationally syndicated daily radio show, “Keepin’ It Real,” that broadcasts on dozens of Sirius XM stations. The reverend remains a busy man.

“I do not feel that the people that poured into me would expect me to do anything less,” the Rev. Al said. “And that’s who I am. I’m going to do this until I die. Put your ear down to the casket, and I’ll be saying ‘no justice, no peace’ as they lower me all the way down.”